'It's a Sin to Tell a Lie'

Description

By the end of his life, Billy Mayhew might well have wished he’d never written that damned song.

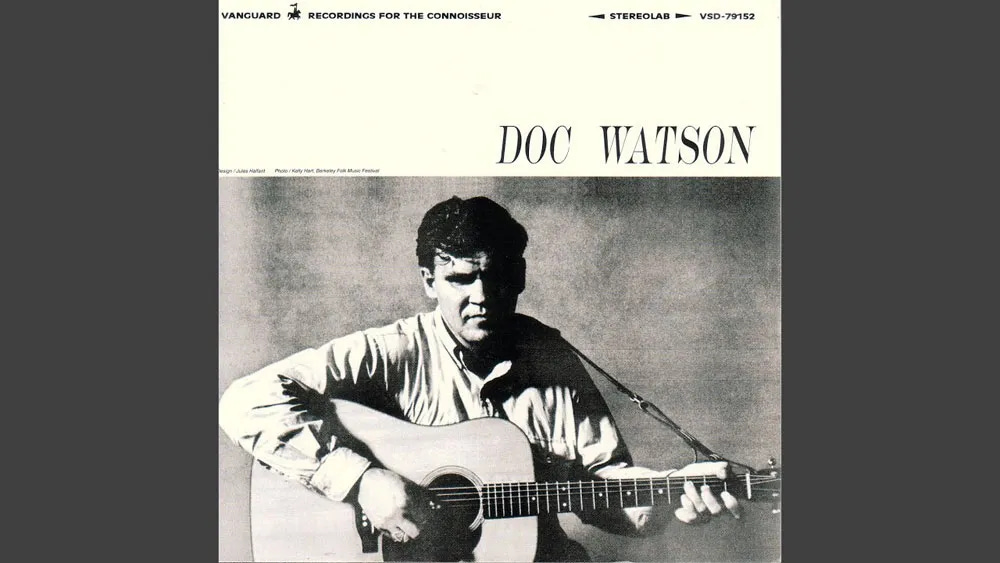

Oh, it was a hit, all right — the only one the old Baltimore vaudeville piano man ever wrote — introduced to the world by 1930s radio superstar Kate Smith and later jazzed up by the great Fats Waller who got everyone humming the thing.

Still, within months of the publication of “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie,” Billy and his wife and co-author Margaret Konig Mayhew were dragged into court with a demand that they share the song’s mounting royalties.

How the Song Came to Be

Billy wrote “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie” in the early 1930s, but after five years of hoofing it around to pitch it in New York’s Tin Pan Alley, he could find no one who wanted to publish it. According to later court documents, Mayhew was about to give up when in June 1935 he met Helen Meehan in the music department of the S.S. Kresge Company store in Baltimore.

For nearly two decades by then, Meehan had been employed as a sheet music buyer, meaning she had contacts in the publishing world. Right away, Helen went to bat for Billy, reaching out to representatives of music houses. In early 1936 she landed the song with Broadway publisher Donaldson, Douglas and Gumble, Inc. (If that name rings a bell, it might be because we met the firm’s founder Walter Donaldson back when we talked about his “My Blue Heaven” and again in the back story of his “Makin’ Whoopee.”)

When Donaldson published it, “It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie” hit the big time. It was first recorded and released by Freddy Ellis and his orchestra, followed by Kate Smith and then Fats Waller. Dream come true. But before the year was out, Billy’s dream took a nasty turn.

The Court Case

In the Circuit Court of Baltimore City in late July 1936, Helen Meehan sued him, claiming Billy Mayhew himself had done a bit of lying when he promised to give her 50 percent of the royalties if she got the song published. After a two-year court fight, a decree was issued in Meehan’s favor, establishing her as a creditor for $7,163.10 (about $170,000 in today’s dollars). This decision was affirmed on appeal the following spring.

However, it appears only the lawyers profited from the case. While Helen Meehan successfully established her claim, she found it hard to collect. Her main obstacle was a representative of the song’s publisher, which placed an attachment on Mayhew’s royalties in New York as early as February 1937.

In a desperate attempt to stop that payment, Meehan filed an involuntary bankruptcy petition against the Mayhews, arguing that Billy and Margaret’s failure was a “preferential transfer.” But the U.S. District Court didn’t buy it, dismissing her petition and ruling that the publisher’s claim was based on a lien established years earlier and therefore was not a fresh act of bankruptcy.

The Last Decade

After that, we lose track of Helen, but Billy and Margaret Mayhew ended their days living and working at a brother-in-law’s boarding house and “truck farm.” Today, incidentally, the farm — located on Bar Neck Road in Cornersville, in Maryland’s Dorchester County — is listed on the state’s Inventory of Historic Properties, all because of its association with the song.

No more hit songs came from the couple, though they seem to have kept trying. For instance, the day after Christmas in 1940, Billy and Margaret filed copyright papers for a composition with an intriguing title: “Can’t Do a Thing with My Heart.” Alas, we find no indication that it was ever published or recorded.

Billy died Nov. 17, 1951, and Margaret died a month later. Both are buried in Baltimore’s Oak Lawn Cemetery.

The Song Lives On

The Mayhews wrote the song as a waltz, and that’s how Freddy Ellis’s orchestra performed it in its first recording.

The early performances — by Kate Smith, Ruth Etting, Vera Lynn, et al — played it straight (very straight).

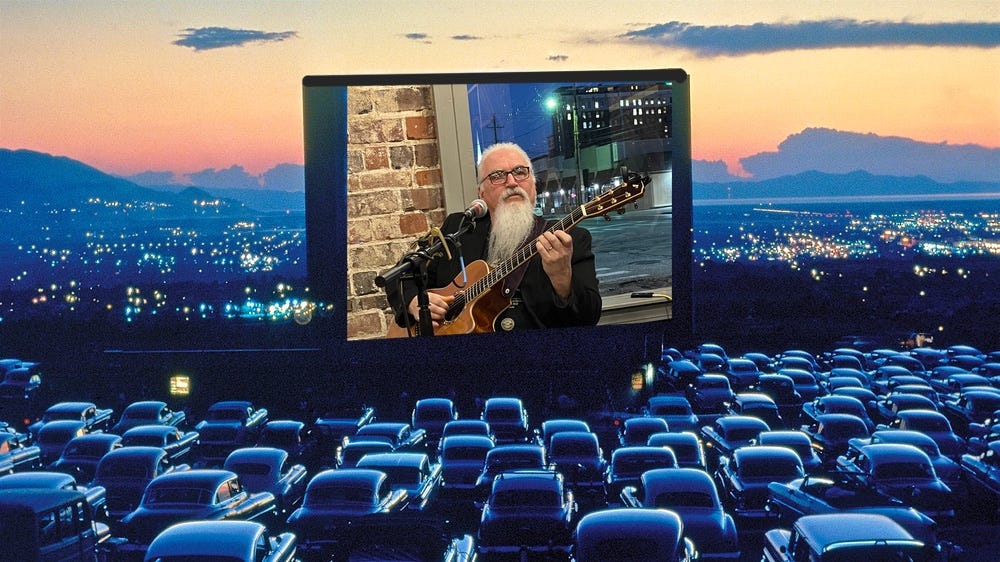

But then also came Flood hero Fats Waller, who never played anything straight. Fats kicked the tune into 4/4 and gave it his signature blend of stride piano and irreverent, satirical humor. For instance, while the ladies Kate, Ruth and Vera all loyally sang the Mayhews’ original lyric “If you break my heart I’ll die,” Fats ad libbed, “If you break my heart, I’ll break your jaw!”

From Fats forward, the song that originated as a sappy Tin Pan Alley ballad got its groove on, transforming into a high-energy (often comedic) jazz performance for everyone for the Ink Spots (1942) and Billie Holiday (1949) to Jimmy Rushing (1955) and Tony Bennett (1964) to Steve Goodman (1975) and John Denver (1998).

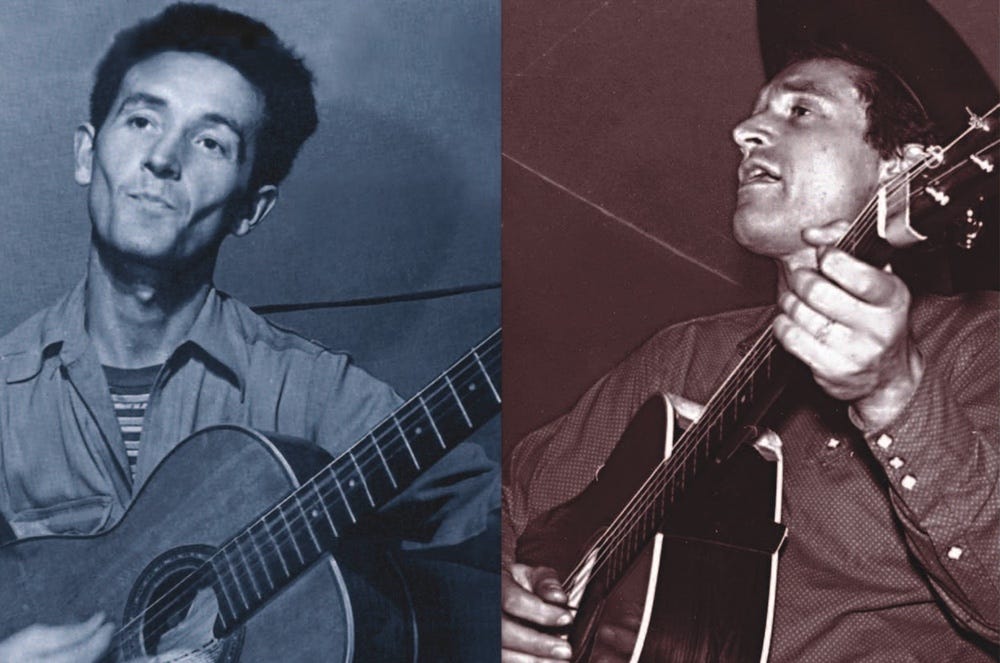

Floodifying It

This song has rattled around in the Floodisphere for decades but only recently did we decide to give it a spin. Whaddaya think?

More Song Histories

Do you enjoy this back stories on the songs we play? We got a million of ‘em! Well, hundreds, anyway.

Drop by the free “Song Stories” archive — just click here to reach it — and you’ll find an alphabetized list of titles. Click on one to reach our take on that particular tune.

Or if you’d like to find songs from a specific decade, visit the archive’s “Tunes on a Timeline” department — click here! — to locate songs by their years of origin.

This is a public episode. If you would like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit 1937flood.substack.com