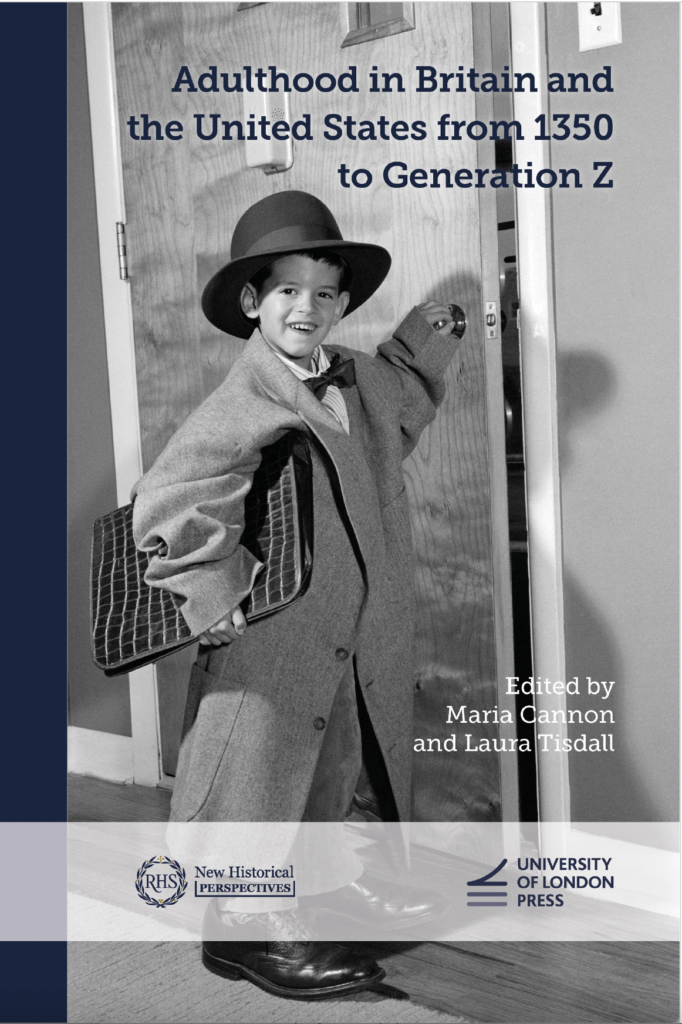

Adulthood in Britain and the United States from 1350 to Generation Z

Description

This post first appeared on the blog of the Royal Historical Society, a partner in the New Historical Perspectives publishing series.

Adulthood has a history. In this post, Maria Cannon and Laura Tisdall introduce their new edited collection Adulthood in Britain and the United States from 1350 to Generation Z which explores how concepts of adulthood have changed over time in Britain and the United States.

Expectations for adults have altered over time, just as other age-categories such as childhood, adolescence and old age have been shaped by their cultural and social context.

Collectively, the volume’s authors explore four key ideas: adulthood as both burden and benefit; adulthood as a relational category; collective versus individual definitions of adulthood; and adulthood as a static definition.

Adulthood in Britain and the United States from 1350 to Generation Z (November 2024) is the 20th volume in the Society’s New Historical Perspectives series published by the University of London Press. All 20 titles are available as free Open Access editions as well as in paperback print.

‘Is Western culture stopping people from growing up?’ asked The Economist in August 2024. In case the reader didn’t get the point, the article added a subheading: ‘RIP adulthood’.[1] The Economist is not the first or last media outlet to tell us that adulthood is disappearing. Popular anxieties in the press and on social media claim we’re afflicted by a plague of ‘kidults’ who are doing ‘adulting’ wrong.

The usual target is our generation—millennials—born between 1981 and 1996, who are supposedly failing to meet traditional milestones of adulthood. Sometimes, it’s not our fault. Sonia Sodha wrote recently in the Observer that millennials are inhabiting a ‘stretched adolescence’ because of the rising numbers living with parents; but, she allows, they are not to blame as they didn’t choose this ‘Peter Pan lifestyle’: this failure to launch is due to ‘harsh economic realities’ such as higher rents and soaring inflation.[2]

Achieving the status of adult has always been shaped by intersectional identities of gender, race, class, sexuality and disability.

Sometimes, however, it is our fault. ‘Why the choice to be childless is bad for America’ blared a Newsweek headline in 2013.[3] Millennials who are supposedly choosing to remain ‘childfree’ are pigeonholed as intrinsically selfish and irresponsible—in other words, as not proper adults. They are blamed for not producing the next generation of workers who can support an ageing population, and for not providing their parents with the emotional satisfaction of grandchildren.[4] This is in spite of the fact that it is as yet unclear whether this demographic trend is better characterised as childlessness or delayed childbearing.[5]

The next generation down, Generation Z, born between 1997 and 2012, are also doing adulthood wrong. But in contrast to ‘spoilt’ millennials, who have been seen as unreliable employees since they first started entering the workplace, Gen Z are often portrayed as ‘old before their time’. Rather than ‘Generation Me’, they are ‘Generation Sensible’, missing out on the partying that ought to define adolescence and young adulthood.[6] Growing up too fast is, apparently, just as bad as not growing up at all.

This fraught debate reveals both how historically contingent our idea of a ‘right kind’ of adulthood is. ‘Fifty years ago, the average 24-year-old would have been married, living with their partner, and probably already a parent,’ Sodha argues. But in the early 1970s, British people were getting married and having children younger than ever before. These were anomalous decades, not a yardstick of normality.

The collection addresses two central questions: who gets to be an adult, and who decides?

Our new edited collection, Adulthood in Britain and the United States from 1350 to Generation Z, touches on themes that have framed people’s worries about, and experiences of, adulthood over the past six centuries. Older people have told younger people throughout history that they need to step up to their responsibilities. Ask the medieval monks who despaired over the ‘childishness’ of newly recruited men, who, as the Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux put it in the twelfth century, were ‘vehemently indiscreet, indeed absolutely intemperate, and exceedingly stubborn’.[7]

Adults themselves have struggled with successfully ‘adulting’. J.B. Atkins, a British journalist, remembered ‘the profound and surprising satisfaction’ he felt in 1896 when he realised he would never again have to ask his father for any money; Atkins was already twenty-five at the time.[8]

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large is-resized">

</figure>

</figure>The collection is the first to employ adulthood as a category of analysis, thus providing a crucial intervention for all scholarship that addresses power and inequality. As scholars of childhood and old age have shown, age has been a significant factor shaping power structures and individual experiences in different cultural and social contexts. Adulthood as a life stage is no different. It has been subject to changing expectations and norms and has never been a static phase in the life course. Achieving the status of adult has always been shaped by intersectional identities of gender, race, class, sexuality and disability. The collection addresses two central questions: who gets to be an adult, and who decides?

The chapters in the collection cover more than 600 years and two continents. Each demonstrate the importance of examining adulthood as a category of analysis, focused around four key themes: adulthood as both burden and benefit; adulthood as a relational category; collective versus individual definitions of adulthood; and adulthood as a static definition.

Several chapters use personal source material to examine individual definitions of adulthood and how they might differ from collective ones.

Highlighting the benefits and burdens of adult status, Holly N. S. White shows in her chapter on seduction suits in early America that for white women, female dependence could be used to benefit a family’s reputation, while undermining their adulthood and independence. In the context of late twentieth century Scotland, Kristin Hay examines the benefits of contraception that young women could access, despite the burden of being denied sexual and reproductive autonomy based on societal perceptions of their maturity. Jack Hodgson’s chapter considers how far a conception of adult