ChatGPT-5 and the end of naive AI futurism

Description

First published at The Future, Now and Then

OpenAI’s release GPT5 feels like the end of something.

It isn’t the end of the Generative AI bubble. Things can, and still will, get way more out of hand. But it seems like the end of what we might call “naive AI futurism.”

Sam Altman has long been the world’s most skillful pied piper of naive AI futurism. To hear Altman tell it, the present is only ever prologue. We are living through times of exponential change. Scale is all we need. With enough chips, enough power, and enough data, we will soon have machines that can solve all of physics and usher in a radically different future.

The power of the naive AI futurist story is its simplicity. Sam Altman has deployed it to turn a sketchy, money-losing nonprofit AI lab into a ~$500 billion (but still money-losing) private company, all by promising investors that their money will unlock superintelligence that defines the next millennium.

Every model release, every benchmark testing success, every new product announcement, functions as evidence of the velocity of change. It doesn’t really matter how people are using Sora or GPT4 today. It doesn’t matter that companies are spending billions on productivity gains that fail to materialize. It doesn’t matter that the hallucination problem hasn’t been solved, or that chatbots are sending users into delusional spirals. What matters is that the latest model is better than the previous one, that people seem to be increasingly attached to these products. “Just imagine if this pace of change keeps up,” the naive AI futurist tells us. “Four years ago, ChatGPT seemed impossible. Who knows what will be possible in another four years…”

Flux covers the intersection of politics, media, and technology. Join our mailing list today to stay in touch.

Naive AI futurism is foundational to the AI economy, because it holds out the promise that today’s phenomenal capital outlay will be justified by even-more-phenomenal rewards in the not-too-distant future. Actually-existing-AI today cannot replace your doctor, your lawyer, your professor, or your accountant. If tomorrow’s AI is just a modest upgrade on the fancy chatbot that writes stuff for you, then the financial prospects of the whole enterprise collapse.

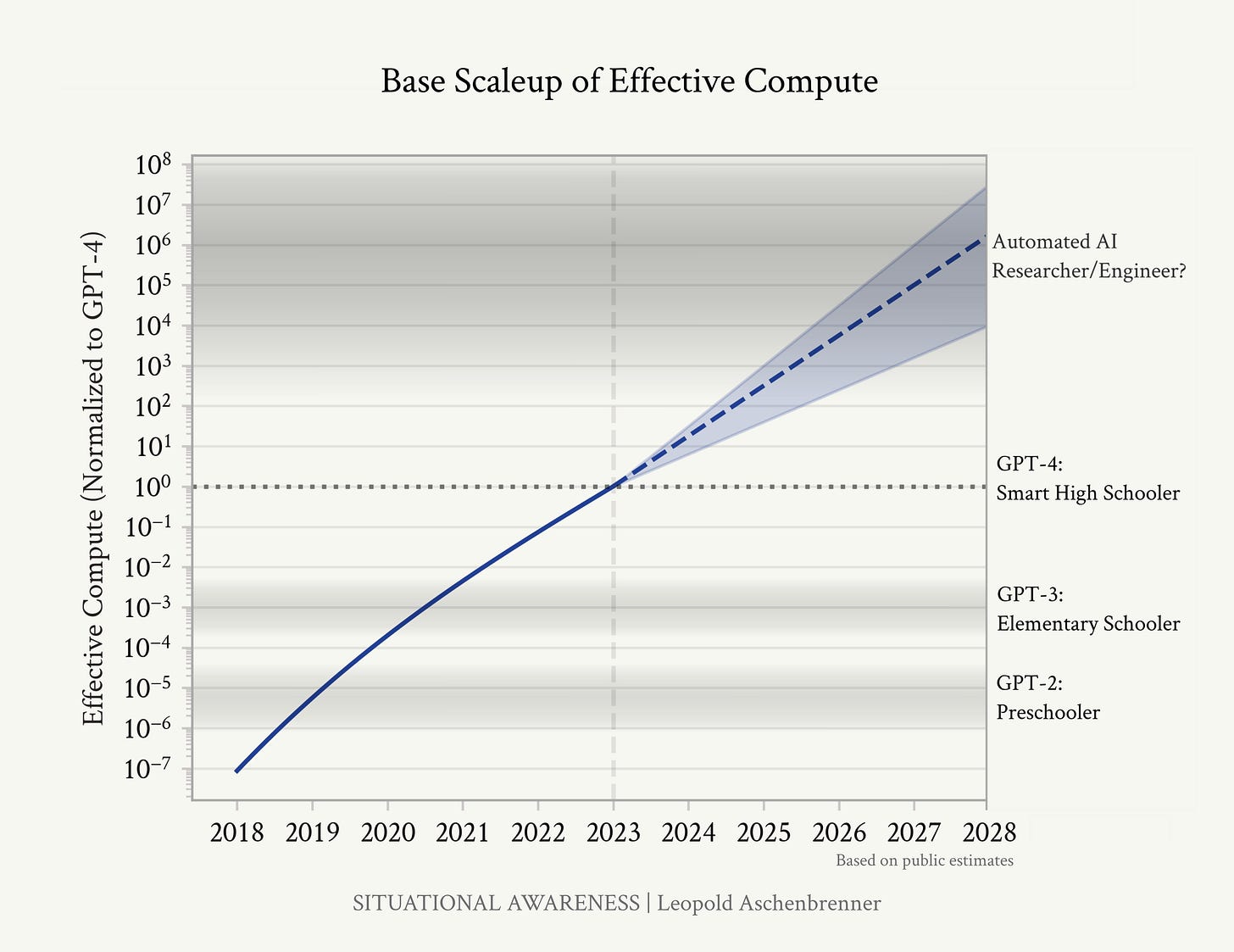

And so we have been treated to years of debates between AI boomers and AI doomers. They all agree that our machine overlords are on the verge of arrival. They know this to be true, because they see how much better the models have gotten, and they see no reason it would slow down. Leopold Aschenbrenner drew a lot of attention to himself in 2024 by insisting that we would achieve Artificial General Intelligence by 2027, stating, “[it] doesn’t require believing in sci-fi; it just requires believing in straight lines on a graph.” More recently, the AI 2027 boys declared that we had about two years until the machines take over the world. Their underlying reasoning can be summed up as “well, GPT3 was an order of magnitude better than GPT2. And GPT4 is an order of magnitude better than GPT3. So that pace of change probably keeps going into infinity. The fundamental scientific problem has been cracked. Just add scale.”

The most noteworthy thing about the public reaction to GPT5 (which Max Read summarizes as “A.I. as normal technology (derogatory)” is that it blew no one’s mind. If you find ChatGPT to be remarkable and life changing, then this next advance is pretty sweet. It’s a stepwise improvement on the existing product offerings. But it isn’t a quantum leap. No radical new capabilities have been unlocked. GPT5 is to GPT4 as the iPhone16 is to the iPhone 15 (or, to be charitable, the iPhone 12).

And that’s a problem for OpenAI’s futurity vibes. The velocity of change feels like it is slowing down. And that leaves people to think more about the capabilities and limitations of actually-existing AI products, instead of gawking at imagined impending futures.

Here’s a visual example. Take a look at this graph: