Contemplation and the Cross

Update: 2025-10-11

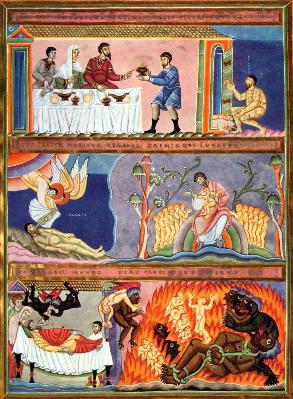

Description

By Dominic V. Cassella

In Herodotus' Histories from the 430s BC, we read of a wise Greek philosopher and political thinker, Solon. While traveling, Solon met the King of Lydia, Croesus, who was known for his immense wealth. Croesus asked the philosopher what he thought about his great riches and whether such wealth meant that he, Croesus, was the happiest man alive.

To that, Solon replied that you can "Call no man happy until he is dead."

Solon's point is that as long as someone is living, though they may be happy today, fortunes change, and bad decisions are made that can result in the fall of even the most well-off and mighty.

Now, we should ask: Is Solon right? Is it only the dead whom we can call happy?

To this, the Christian says "yes." It just depends on how you are dead. For if you are dead to sin (Romans 6:11 , 1 Peter 2:24 ), having been crucified with Christ (Galatians 2:20 ), then your true life is hidden with Christ in God (Colossians 3:3). This is because, if we die with Christ, "we will also live with Him" (2 Timothy 2:11 ), and in this life in Christ we find true happiness.

But what, concretely, does all this mean? How can we live this new life in Christ? And what is it to take up the Cross (Matthew 16:24 , Mark 8:34 , and Luke 9:23 ) and be crucified with Him?

In Fr. Thomas Joseph White's latest book, Contemplation and the Cross: A Catholic Introduction to the Spiritual Life, we are given a comprehensive answer to these questions. Originally put together as a spiritual retreat for a Catholic religious order, Contemplation and the Cross also serves as a sequel to an earlier work of Fr. White's The Light of Christ: An Introduction to Catholicism (reviewed by Robert Royal here).

In this new book, the same perspicacity and readability are present as they were in the prequel. Fr. White - a Dominican and now Rector Magnificus of the Pontifical University of St. Thomas (the Angelicum) in Rome - has written with the express purpose of offering the reader two different resources, which are evident in the body of the text and the footnotes. This is a book that can be read through for its own lucid exposition of the Catholic tradition, or scanned for its rich references for further study in figures such as Thomas Aquinas, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, as well as modern magisterial texts.

Each chapter identifies and explores a "cause" of the Catholic spiritual life. The primary source and efficient cause of the spiritual life is God Himself. So the first chapter begins with the "final" cause - the "why" or "goal" of the spiritual life. In this unusual opening, we immediately see the difference it makes to view things in the light of Christ.

Man, by nature, gropes in shadows as he reaches for the truth. In the covenant of the Old Testament, the Law served as a guardrail to prevent God's chosen people from holding on to what is self-destructive. With the coming of Light, who is Jesus Christ, we are no longer in darkness but have been offered "grace and truth." (John 1:16-17, John 17:17 )

But what is this spiritual life and what are the means by which we live it? Here we find the relevance of the Cross which, as the new tree of our redemption, repairs the damage done by the old tree at the Fall. In emptying Himself, the Son of God has taken on the poverty and slavishness of human nature and has become obedient "even unto the Cross." (Philippians 2:7-8) It is through His assumption of human flesh and crucifixion that He redraws "the lines of our humanity from within and [reorients] us toward God anew."

The Cross, then, is where we find the exemplar of obedience to God. In contemplating Christ crucified, we find as our model the virtues of righteousness. And in Mary, His mother, we see the exemplar of what it means to live our lives with eyes upon the Cross. In grace and truth, we possess the means by which we unite ourselves to Christ and "become recipient of the mercy of God and a servant or steward of divine mercy."

Cen...

In Herodotus' Histories from the 430s BC, we read of a wise Greek philosopher and political thinker, Solon. While traveling, Solon met the King of Lydia, Croesus, who was known for his immense wealth. Croesus asked the philosopher what he thought about his great riches and whether such wealth meant that he, Croesus, was the happiest man alive.

To that, Solon replied that you can "Call no man happy until he is dead."

Solon's point is that as long as someone is living, though they may be happy today, fortunes change, and bad decisions are made that can result in the fall of even the most well-off and mighty.

Now, we should ask: Is Solon right? Is it only the dead whom we can call happy?

To this, the Christian says "yes." It just depends on how you are dead. For if you are dead to sin (Romans 6:11 , 1 Peter 2:24 ), having been crucified with Christ (Galatians 2:20 ), then your true life is hidden with Christ in God (Colossians 3:3). This is because, if we die with Christ, "we will also live with Him" (2 Timothy 2:11 ), and in this life in Christ we find true happiness.

But what, concretely, does all this mean? How can we live this new life in Christ? And what is it to take up the Cross (Matthew 16:24 , Mark 8:34 , and Luke 9:23 ) and be crucified with Him?

In Fr. Thomas Joseph White's latest book, Contemplation and the Cross: A Catholic Introduction to the Spiritual Life, we are given a comprehensive answer to these questions. Originally put together as a spiritual retreat for a Catholic religious order, Contemplation and the Cross also serves as a sequel to an earlier work of Fr. White's The Light of Christ: An Introduction to Catholicism (reviewed by Robert Royal here).

In this new book, the same perspicacity and readability are present as they were in the prequel. Fr. White - a Dominican and now Rector Magnificus of the Pontifical University of St. Thomas (the Angelicum) in Rome - has written with the express purpose of offering the reader two different resources, which are evident in the body of the text and the footnotes. This is a book that can be read through for its own lucid exposition of the Catholic tradition, or scanned for its rich references for further study in figures such as Thomas Aquinas, the Fathers and Doctors of the Church, as well as modern magisterial texts.

Each chapter identifies and explores a "cause" of the Catholic spiritual life. The primary source and efficient cause of the spiritual life is God Himself. So the first chapter begins with the "final" cause - the "why" or "goal" of the spiritual life. In this unusual opening, we immediately see the difference it makes to view things in the light of Christ.

Man, by nature, gropes in shadows as he reaches for the truth. In the covenant of the Old Testament, the Law served as a guardrail to prevent God's chosen people from holding on to what is self-destructive. With the coming of Light, who is Jesus Christ, we are no longer in darkness but have been offered "grace and truth." (John 1:16-17, John 17:17 )

But what is this spiritual life and what are the means by which we live it? Here we find the relevance of the Cross which, as the new tree of our redemption, repairs the damage done by the old tree at the Fall. In emptying Himself, the Son of God has taken on the poverty and slavishness of human nature and has become obedient "even unto the Cross." (Philippians 2:7-8) It is through His assumption of human flesh and crucifixion that He redraws "the lines of our humanity from within and [reorients] us toward God anew."

The Cross, then, is where we find the exemplar of obedience to God. In contemplating Christ crucified, we find as our model the virtues of righteousness. And in Mary, His mother, we see the exemplar of what it means to live our lives with eyes upon the Cross. In grace and truth, we possess the means by which we unite ourselves to Christ and "become recipient of the mercy of God and a servant or steward of divine mercy."

Cen...

Comments

In Channel