Ep 106: Is everything really meaningless? (Ecc 1:1-11).

Description

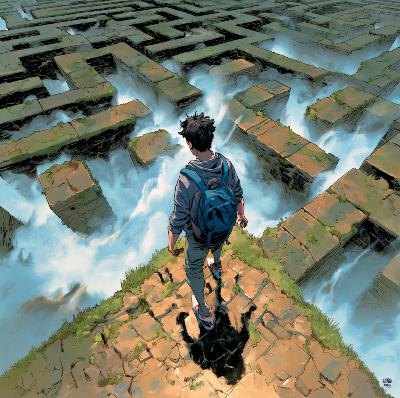

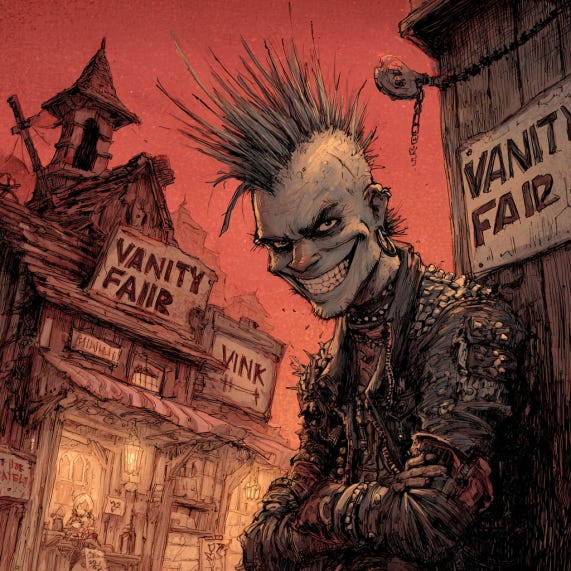

The door in front of you is ancient oak and black metal. The stonework of the walls towers above, worn smooth by time, and half consumed by the deep green ivy splashed across the grey colourscape. A pale mist moves slowly in the air, hanging before these portals. The forest behind you is quiet in the early morning chill, and the distant birdsong hails a sunrise yet to come. The dull yellow light of the lanterns is caught visibly in the morning air, suspended in the morning mist. This labyrinth has outlived empires.

Welcome to the door of the labyrinth, because that is what Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 really is.

This passage introduces us to the themes and questions of the entire book, and in that sense it stands before us as an ancient monolithic entryway into the maze. As we make our approach to the doorway of the labyrinth, I want you to open your imagination and try to visualize what’s before you. This maze, as we come to it, is vast. As you walk up to the entrance, on either side you see again those great stone walls spreading out in either direction. As you look at the door itself, what stands before you is a great set of twin oaken panels, closed fast. Each one of these panels represents a mystery – the twin mysteries that will be turned over in our minds and considered again and again as the book unfolds. Verse two lays out these twin enigmas before us in a single expression: “Vanity of vanities, says the Preacher, vanity of vanities! All is vanity.”

This phrase is one of the most famous and well-known verses in all of scripture, but it is also one of the most troubling. “Vanity, vanity, all is vanity!” Why in the world would a Christian, of all people, say that everything is vanity? Now to help you to understand this, I want to begin by giving you a lesson in Hebrew. I want you to forget the word vanity for a moment. Where verse two says “vanity,” I want you to insert the word: “hevel.” Hevel, heveleem, says the preacher, hevel, heveleem, all is hevel!” (that’s a rough English equivalent of the Hebrew word, by the way!). This is what I want you to do: every time you hear the word “vanity” I want you to replace it with the word “hevel.”

Now, unless you’ve studied Hebrew, chances are that this word means nothing to you, which is exactly why I want you to use it. Because the truth is that “vanity” is an unfortunately limited translation. When we say “vanity,” in English, we’re calling to mind ideas like: “pointless, meaningless, etc,” but these are not the main ideas that the Preacher is trying to convey. There are times when he does use this word with a nuance of frustration, but “meaningless” is far from the dominating concept that’s on his mind.

What is “hevel”? Literally speaking, it means: “breath.” More literally, then, you could translate verse two as saying: “A breath! A breath! Says the preacher, all things are but a breath.” “Vaporous” also captures the meaning here. All of a sudden, that expression makes a whole lot more sense doesn’t it? A Christian wouldn’t call life meaningless, but vaporous, that makes sense. And so what Solomon is primarily doing with this word is that he’s using an image to express his idea. “Vanity” represents an attempt to translate the imagery of a breath into a concept. I suggest that it’s better to keep the image. After all, we often use images ourselves to convey meaning.

You might see a powerful rugby player and say: “He’s a beast!” He’s not actually a beast, of course, but he’s strong and powerful, and plays the game hard. We might also say something like: “University is a doorway to the future,” or: “The office is a hive of activity.” We use metaphors like this to communicate something about a concept or idea, and that’s what Solomon is doing here.

Solomon is saying: “A breath! A breath! All things are but a breath!” Now when we say a man is a beast, we’re highlighting his strength and his savagery. When we say an office is a hive, we’re highlighting that it is full of activity. When Solomon describes “all things” under the sun as being a breath, he’s highlighting two things (and these two ideas form the twin doors of our labyrinth). First, he’s highlighting the temporary nature of things (a breath is gone in a moment). Secondly, he’s highlighting the lack of substance in the things of this world. As a breath is insubstantial, it cannot be grasped or held, so too is this life under the sun. We cannot hold on to it. It is short, and it is fleeting – insubstantial, impossible to grab hold of. The shortness of life, and the temporary nature of all things – these are Solomon’s key themes in this book.

So then, contrary to the “vanity” translation, the Preacher is not saying that everything is vain, or meaningless, although that sense may be conveyed inasmuch as things are fleeting and insubstantial. And, again, there are times when Solomon does use hevel to highlight that something is meaningless or frustrating, but his purpose here is certainly not to say that all things are meaningless – that is a misreading of the text, and sadly one which is very widely in vogue. After all, you only need to read further in the book to see that he doesn’t think everything is meaningless. There are plenty of times when he commends certain things as good. There is more gain in wisdom than in folly (Ecc 2:13 ), it is a good thing to eat, drink, and enjoy your work (Ecc 2:24 ). These are not the comments of a man who literally thinks everything is meaningless. The idea that everything is meaningless is likewise at theological odds with the rest of scripture, and so we must reject it on that basis as well.

Again, to be sure, there is a certain frustration that comes with the temporary nature of life in a fallen world – particularly in a life where one does not fear God. We may indeed struggle with a sense of meaninglessness in life at times, and the Preacher is candid about that struggle at different points. Nonetheless, he does not say that all things are vain or meaningless. It is a very limited and misleading translation of hevel. Again – Solomon’s point is not to say life is meaningless, his point is to highlight how quickly life passes, and how insubstantial the things of this life really are.

And so we have the two doors to this labyrinth of Ecclesiastes: the first door is the recognition that life is short, and the second door is the recognition that the things of this life are insubstantial, transient, or passing – impossible to hold on to. The doors now stand open before us – we’ve unlocked their mystery!

As we step inside, we then see Solomon develop these themes further in verses three and four. We see in verse four that he wants us to know how short life really is, how quickly it passes: “A generation goes, and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever.” And he also wants us to see that there is a certain lack of substance in the things that we do in our lives under the sun in verse 3: “What does man gain by all the toil at which he toils under the sun?”

You see the frustration there don’t you? A man might work his whole life, and yet he himself disappears and no longer gains anything from his work. It’s as though a man breathes a puff of smoke on a cold morning, and he tries to take hold of it. It simply disappears in his fingers, it is a chasing after the wind.

Life is a short and insubstantial thing – these are the twin realities that Solomon calls us to consider. I’m emphasizing this and repeating myself here because it’s so important that you get this – many commentators don’t. And, as you think about it on a personal level, these observations are true aren’t they? Life is short. Things quickly change. And the things of this world, however hard we may work, we cannot hold on to them. You could spend your whole life working, and you get to the end – and what have you gained? We pass away, and money won’t do us any good. Degrees, successful businesses, possessions – we can’t hold on to them, and so what have gained from all our toil?

And it’s short too. Verse 11 says: “There is no remembrance of former things, nor will there be any remembrance of later things yet to be.” It’s so true. Within just a few generations, our lives are nothing but a few words on www.ancestry.com. Let me put it this way: what do you know about your great, great grandparents? Most of us wouldn’t even know their names. And even if you know their names, what do you know about their lives? Their struggles? Their desires? Achievements? Failures? The truth of the matter is that within just a few short years, each one of us will be in the same position. Our great-great grandchildren will not know our names. And so the Preacher’s purpose is to bring our attention to just how short and insubstantial life really is, to show us how insubstantial our labours in this world really are.

And the truth is that we need this reality check, because we tend to think of things as permanent and lasting, don’t we? The world around us, our homes, our church buildings, the earth beneath our feet, they all feel very solid don’t they? And yet time will surely wear them away. Riches similarly give people a sense of security. Our jobs, our health, our insurance policies. All of these things are walls in our self-made fortresses of security in this world. We build them up, and surround ourselves with them, and as we sit upon our self-made thrones, we think we are secure. But any one of these things could disappear in a moment. When your doctor tells you that you have cancer. When stock markets fail. When fires destroy homes. When car crashes take lives. We have no guarantee whatsoever that we will be alive tomorrow. And – what’s more – we have no guarantee whatsoever that things today will be the same tomorrow. Our money, our homes, possessions, they could all disappear at a moment