Here’s Something You CAN Do Outside: Stargazing. Our Easy Guide to the Night Sky

Description

If you’ve never really learned about the night sky, now is a great time do it. Parents can teach their children about the stars, and anyone can get out of the house and stargaze, keeping plenty of appropriate physical distance.

So, on a clear evening, stop streaming movies, step outside, and look up! Here’s your guide to how and what to see.

Keep it Simple

The early spring has one of year’s most magnificent evening displays of bright stars. So, even if you live in the city, where stars compete with urban light pollution, you can still see a lot.

<figure id="attachment_1959848" class="wp-caption aligncenter" style="max-width: 800px">

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">A layer of low fog over the East Bay highlights the problem of urban light pollution, the light from cities that sets the atmosphere above aglow and makes stargazing a challenge. (Carter Roberts)</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">A layer of low fog over the East Bay highlights the problem of urban light pollution, the light from cities that sets the atmosphere above aglow and makes stargazing a challenge. (Carter Roberts)</figcaption></figure>It’s easy to get overwhelmed by the number of stars up there. The best advice for beginners is this: pick one specific region of the sky, and get to know what’s there. Don’t worry about learning the names of all the stars and the constellations. That can come later.

A Sampler Pack of the Evening Spring Sky

To begin, here’s a way to choose a small patch of the night sky.

Over the next few weeks, after the evening twilight has faded, around 8 or 9 p.m., find a safe location nearby, one with a clear view of the sky. Get comfortable, and look to the southwest — to the left of where the sun set.

Venus

The first thing you will notice is an extremely bright object shining almost directly west, a couple of hand-spans above the horizon. It is intense, and, unlike the stars around it, shines steadily without twinkling. It’s not a star; it’s the planet Venus. Fun fact: Planets don’t twinkle.

<figure id="attachment_1959845" class="wp-caption aligncenter" style="max-width: 800px">

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">The southwestern portion of the sky in late March, around 9:00 p.m. Image created using the free desktop planetarium software, Stellarium. (Stellarium)</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">The southwestern portion of the sky in late March, around 9:00 p.m. Image created using the free desktop planetarium software, Stellarium. (Stellarium)</figcaption></figure>Venus is currently playing its role as the “Evening Star,” and will remain in the early western sky for several weeks to come. As the weeks pass, though, Venus will start sinking into the twilight. And by mid-May, the planet will disappear in the glow of dusk.

Venus is the brightest of the planets, and the third brightest object in the sky, outshined only by the moon and sun. Here’s why: first, Venus is very close to Earth — so close that the light entering your eyes bounced off Venus only minutes ago! Second, it’s a big planet, about as big as Earth. And, third, Venus is completely covered in cloud and reflects much of the sunlight shining on it.

Sirius, the Dog Star

In addition to Venus, you will find several very bright stars across this patch of sky.

Far to the left, almost directly to the south and about the same distance above the horizon as Venus, is the brilliant star Sirius, also called the “Dog Star,” because it belongs to the constellation Canis Major, the “Greater Dog.”

Sirius appears bluish-white, but you might see glints and flashes of prismatic colors in its light as it twinkles: red, green, yellow. This is caused by the refraction of Sirius’ light in Earth’s atmosphere, the same phenomenon that produces rainbows from water droplets and the spectrum of colors split by a prism.

Sirius is bright enough to stimulate the color-sensitive “cone” cells in your retinas, not just the black-and-white “rod” cells. In general, stars are not bright enough for your eyes to detect any color, though there are exceptions.

Betelgeuse

One of those exceptions can be found near Sirius. Look up and to the right of Sirius and you will find the bright orange-red star, Betelgeuse. Betelgeuse is located at the “shoulder” of the constellation Orion, the Hunter.

Betelgeuse’s color isn’t caused by refraction in Earth’s atmosphere. It comes from the star itself. Betelgeuse is a “red giant” star, an older star that has blown up to an enormous size, over 800 times larger than the sun—which accounts for its brightness.

The Winter Triangle

Sirius and Betelgeuse are two members of a pattern of stars called the Winter Triangle, a large equilateral triangle. The third star of the Triangle is found above Sirius and to the left of Betelgeuse. It’s called Procyon, and it belongs to the constellation Canis Minor, or the Lesser Dog. In Greek mythology, Orion the hunter has two dogs, Canis Major and Canis Minor, marked by Sirius and Procyon.

The Winter Triangle is not a constellation, but a simpler and unofficial pattern of stars called an “asterism.” Like the often more complicated and storied constellations, asterisms help identify different parts of the night sky, like signposts. The sky is full of asterisms, and as you learn more about the skies in different seasons, you’ll learn to recognize them, along with the constellations.

Orion’s Belt

In fact, there’s another asterism not far away from the Winter Triangle. Located below Betelgeuse is a row of three stars that are equally bright, and equally spaced apart. This is Orion’s Belt, one of the easiest star patterns to find and recognize.

Meteor Shower Treat: The Lyrids

With this beginner’s crash course in sky exploration under your belt, you’re in for a treat! There’s an upcoming meteor shower.

<figure id="attachment_1959850" class="wp-caption aligncenter" style="max-width: 640px">

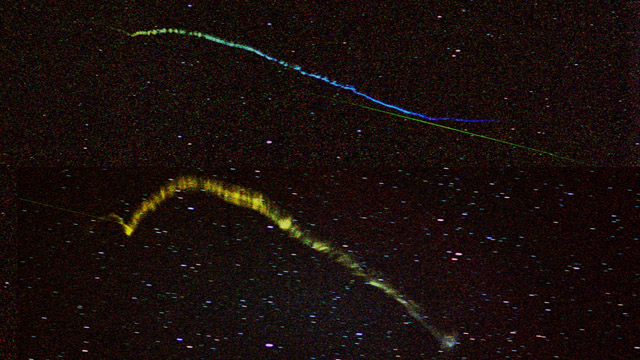

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">Timed exposure image of meteor trails produced by the Leonids meteor shower. (Carter Roberts)</figcaption></figure>

<figcaption class="wp-caption-text">Timed exposure image of meteor trails produced by the Leonids meteor shower. (Carter Roberts)</figcaption></figure>After midnight on April 21st, and throughout the early morning hours of April 22nd, the Lyrids meteor shower will reach its peak of activity for the year, producing as many as 20 meteors per hour. All you must do is stay up past midnight, or set your alarm clock for 2 or 3 a.m., and gaze into the eastern sky until you see one.

Websites for Beginners

There are plenty of online resources to help you explore the night sky and its constellations and asterisms. They can also alert you to upcoming celestial events like meteor showers and eclipses. Here are a few for starters:

There are also several good phone apps, for iOS and Android, that will help you find your way around the sky.

As you gaze casually at the twinkling patterns of stars in your sky, you may find your curiosity teasing you to explore deeper questions about the universe we exist in. How far away are the stars? What are they made of? How big and hot are they really? Do any of them have planets, and w