Historian Richard Tedlow on Bach's Charisma, and Trump's

Description

Historian Richard Tedlow joins me to ask what made Bach charismatic in his own time and ours. He also argues that no matter the political situation, “Bach’s music is going to exist as long as the human race exists and can’t be taken away.” Along the way we consider the charisma of Bernstein, Gould, Clinton, Hitler, and Trump.

Here’s Richard’s Substack.

Playlists of works referenced in this episode, including those by Shostakovich, Bach, Brahms, and Strauss. Apple Music and Spotify below.

Transcript:

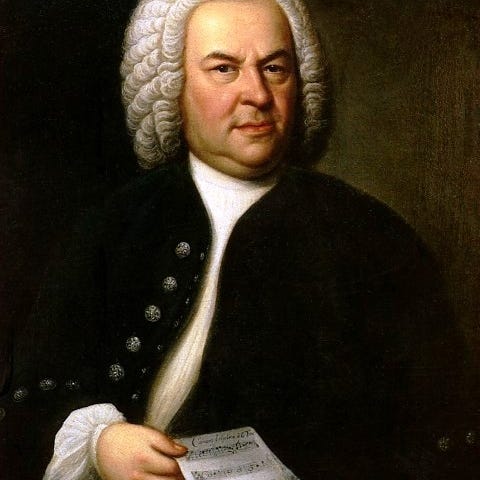

Evan Goldfine: Hello, and welcome to the fifth episode of A Year of Bach. I'm Evan Goldfine. Today my guest is Richard Tedlow, one of our leading historians of business. He was a longtime professor at Harvard Business School and later an instructor at Apple where he taught executives in their internal Apple University. Richard studies how leaders persuade, connect and make decisions how they deceive themselves and others.

And he's put a special focus on the elusive force of charisma in leaders. Today we'll speculate a bit on Bach's charisma and what it might have been, and we can see how charismatic conductors act in the world today. We'll also touch on our president's charisma and Richard's deep connection to Bach's music.

Richard, welcome.

Richard Tedlow: Thank you very much. Pleasure to be here.

Evan Goldfine: Before charisma, let's talk about Bach and your connection to the music itself.

Richard Tedlow: I didn't start music with Bach. One of the characteristics of Bach is that one finds [00:01:00 ] oneself listening to his music without realizing that he composed it.

The Air on the G-string the Jesu, Joy of Man's desiring, this is part of normal sort of living in this world, and you hear it without necessarily connecting it to the name Bach. I've been listening to music seriously since I was a kid. My parents introduced me to it.

The first opera I went to was Carmen with Risë Stevens at the Miami Opera Company in Miami, Florida. And so I've been interested in this kind of music my whole life. I went to Bayreuth three times to hear Wagner's music there. And Bach I began to seriously listen to when I was in college.

I graduated from Yale in 1969. And there I first heard the Cantata 140, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, and other music by Bach, and you realized that this was an [00:02:00 ] extraordinary creative human being.

So here's a question. How much do you have to know? How much do you have to sort of work, if you will to how much does music have the right, if you will, to ask you to invest in it, in order to get the most out of it? Versus to what extent does music hear itself? So you're not involved at all, basically.

So move, moving from noise. To really find complex music, how much do you need yourself to invest? And I think the older the music is, and Bach was from 1685 to 1750 the more you have to invest for the most part with the exception of some pieces. The Tocatta and Fugue in D Minor would be a classic example.

Everybody's heard that and they don't necessarily [00:03:00 ] associate it with Bach. On the other hand, at least to me, the Goldberg Variations. You have to concentrate, at least I have to concentrate. And the difference between Glenn Gould's first recording of that set of pieces and the last one is really dramatic.

And I saw when I was at Apple, I saw a remarkable presentation about this, and that presentation greatly increased my own ability to enjoy and appreciate it. So that's a question. How much do you have to know, or how much do you have to invest in order to get the most out of the music as opposed to the music just hearing itself?

Evan Goldfine: What a beautiful question. I think that you can be a passive listener and enjoy it. You can be an active listener and enjoy, and you can be a player and enjoy. And then you can be a scholar to learn about the historical importance and where each of these composers, Bach included, fit on the great timeline of the composers of Western music.

I think you get back what you invest. [00:04:00 ] And even then some. And just like with anything else, you could glance at a book of poetry. You can read Shakespeare Sonnets on the first glance, and there's some nice stuff and you might not get it, but if you really take your time with it, you're going to unearth more and more things.

And, what's great about Bach in particular is that often in some of the pieces, not all of them, but it's a pleasant first listen. And as you listen again, something happens inside as you are processing the multiple moving lines. Often you're hearing different musicians emphasize different parts of the music.

So there's the performance side that you're enjoying, and also the core of the music itself. So if you're playing it yourself on a piano or on a guitar, you see the architecture of how things are moving in order to create this thing that just sounds pleasant or moving even. There's really no way to explain why Cantata 140 might move you to [00:05:00 ] tears.

That's not explicable, and that's the beauty of why we're talking about this today, 300 years after Bach's time. Something about that music has really moved us for centuries and many millions of people. And I've described this as a backwards explanation for something divine.

I've heard one of my favorite musicians, a bassist named Victor Wooten says that music needs us as much as we need the music. Music can be abstract, but if it's not resonating through a person doesn't exist. It's one of the great mysteries and pleasures of life and Bach is one of the greatest exemplars of how to create it with deep meaning and with deep emotion. Because without the emotional connection, it's just a curiosity.

Richard Tedlow: I think that's very well put. I think that there has to be this emotional connection and going through life as you and [00:06:00 ] I are doing, and just encountering curiosities to use your word as opposed to deep emotional connections is not a very fulfilling way to go through life.

So that's one thing that draws one to Bach. What is it about Bach that is magnetic and charismatic, if you will? What is it about it that's so utterly appealing? And I think that once again, to use your phrase, if the first listen is not an invitation, you are not likely to have a second listen or to go to Wagner.

If all you hear is the noise, and there is a lot of it in Wagner. You're not gonna go to the next, listen. So there's gotta be something that resonates with you, some, something that is harmonic with you in this music and Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, is just that's that piece. It works. So why? If Bach could've said it another way, he would've said it another way and he would've been a novelist or a poet or you name it, he said it through his music and by almost by [00:07:00 ] definition tho, those aren't words, even though he is setting words to music.

I think that with the words of music, there is a matching of sound and sense that is very powerful with Bach. Can I play a little one snippet of music

Richard Tedlow: From the B minor mass. Okay. It's the Gratias Agimus Tibi. In other words, we give thanks for your great glory.

Thinking about the B minor mass, the most accessible part of it is the Gloria. You can't miss it, and I only got to this later, but you listen to it and you listen to it and you realize this is really this, this is glorious, if you will.

In addition to the fact that the music is simply beautiful to listen to there is an authenticity about Bach music, which is very hard to capture in words. You have to capture it in music, you have to listen to it. But there's an authenticity, a sense that you are touching the ground truth of a human being and that human being's relationship to [00:09:00 ] the everlasting the divine.

Bach to state the obvious was a profoundly religious Lutheran. And that comes through. I mean the genuine, I mean, in a world where there's so much that's phony, frankly, that to touch something genuine is a large part of the inspiration of Bach and a large part of, if you will, the charisma of him.

So I think that it's the first listen has got to work. Authenticity. The more you discover, the more you listen to it. And with Bach especially, the more you discover as you age and you listen to it, I started listening to this music, to Bach music when I was about 18. I'm gonna be 78 years old tomorrow.

That's a long time. And it's, it sounds different and it moves you in a different way now that I'm elderly than it did when I was a kid.

Evan Goldfine: Could you dig into that a little bit more?

Richard Tedlow: I think [00:10:00 ] that without sounding cliche ridden, which is not something that I want to sound, but Bach touches something fundamental in the human experience.

And the more human experience that one has, the more one can go back to that. And be enriched by his own, if you will. Insights. It's a cheap word. This is music we're talking about, not words. The more you can be touched, which is the real thing. Bach himself as a religious person was profoundly in search of communion.

For him, it was communion with God through Jesus Christ. That's in all his music. And for us, it's communion with him. It's true contact, genuine human contact, which I think we all crave in order to be fully alive. I think there are a couple of ot