Jan Senbergs

Description

Above photo of Jan Senbergs by Riste Andrievski

Click play for my podcast introduction to this interview and scroll down for the transcript.

Podcast listeners click here and scroll down for transcript.

Watch the YouTube video of Jan Senbergs’ studio and work here

Links

- Jan Senbergs’ website

- Jan Senbergs on Instagram

- Jan Senbergs at Niagara Galleries

- Talking with Painters YouTube channel

- Talking with Painters on Instagram

- Talking with Painters on Facebook

- Subscribe to the TWP newsletter

- PDF version of transcript for tablet/desktop

With over six decades of work as a painter, printmaker and draughtsman, leading artist Jan Senbergs has exhibited in over 50 solo shows and has been the subject of three survey shows including a major retrospective curated by the National Gallery of Victoria in 2016. A rare accomplishment.

His art evolved from early masterly screenprints to large scale paintings and with subject matter as varied as urban and natural landscapes, industrial themes, surreal structures and forms and aerial map-like works.

This episode has been a long time coming. Covid threw out our plans for an early 2020 meeting but two years later we met in Jan’s inspirational studio in Melbourne. His voice has been affected by some health issues and so this episode is coming to you by way of transcript (below) and an intro on the podcast.

As I was setting up my audio equipment on the day of the interview, Jan and I chatted about the time he had spent in London in his 20s. We talked about other Australian artists who were there at that time. That’s where the recording of the interview began.

Jan Senbergs

I was the younger artist who came into that area and I didn’t know anybody. I didn’t want to bother the local Antipodeans (laughs) so I usually went out by myself. I headed for the National Gallery on one occasion and ran into Arthur Boyd heading there too. We travelled together on the bus from Pimlico to Trafalgar Square. It was very nice because we walked through the Gallery making comments. It’s lovely to do that with another painter. We walked past one room and Arthur stopped and said, ‘There’s a good painting in this room.’ It was a big dog watching over a dying nymph, by Piero di Cosimo. He was such an interesting painter. Afterwards, Arthur suggested we go and have a drink, so we went across the road and had a couple of beers and then he said ‘You’ll have to excuse me, but I’ve got to go back home. I’ve got a few duties there.’ We shook hands and I never saw him again.

Maria Stoljar

You never saw him again?

JS

No, but what was nice about it was the generosity of the older person to somebody younger who had just arrived.

MS

How lovely. But you knew a lot of famous Australian artists like Fred Williams, for example. He was a friend of yours, wasn’t he?

JS

Yeah, I knew Fred. When I first started showing around, I mixed with some of the older artists. At that time there were hardly any younger artists around. And because I hadn’t gone to an art school, I was very isolated. It’s quite different for artists today. Now there are thousands of young people trying very hard to make good art after their schooling. It’s a different atmosphere. Schools pump out all these people with hopes and ambitions. That’s the reason it’s good to know some of the older painters.

MS

Yes. Like John Brack?

JS

Yes, John Brack was one … Len Crawford, Fred, Roger Kemp – these were heavy-duty Melbourne blokes.

MS

It’s amazing that you, in your early 20s, were hanging out with those people.

JS

Yeah, it was actually. Because I couldn’t get into art school so I’d started working in a silkscreen printing company, which was a terrible bloody job (laughs).

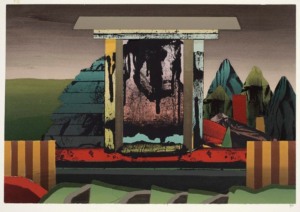

‘Modern monument in colour ‘ 1975,

Colour screenprint, 56.6 x 81.2cm (image)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

MS

Why? Was it heavy work or just dirty work?

JS

Dirty work. Screenprinting was very dirty. It was toxic and unventilated. As an apprentice you’ve got to scrub the screen and so on – you get all the shit jobs (laughs), but that’s understandable.

On Friday nights, though, during the period of the six o’clock closing, I used to go into town. I didn’t want to go with the local trades blokes and drink with them, I’d go straight into Little Collins Street where all the real old lefties hung out – a fantastic atmosphere. They weren’t all painters by any means – there were writers, clapped-out academics and all sorts of people.

MS

Really bohemian.

JS

Yeah, but interesting to me. I went there and I just stood around. They didn’t pay any attention to me, but I was listening. It was an education. A political education as well.

MS

How amazing. So did you keep in contact with those people?

JS

Well, most of them I did, yeah. Including some writers. I was always interested in writing and writers. I used to read a lot when I was younger. The usual standard fare of James Joyce (both laugh).

So I was mixing with all these people at six o’clock closing. There was a frantic atmosphere on a Friday night. There were all these characters coming in from work, and they wanted to have debates and bash out the things that they wanted to talk about. It was interesting.

MS

Yeah, and do you feel like that sort of political leaning comes through in your painting? Do you consciously think about that?

JS

No. I mean, it’s there. How can I put it? I don’t like to be a spruiker for any cause. Your paintings should do that. Usually what happens is that if people are too strident in their political views, they produce paintings which are very single-minded – with a message they want to send, but often the artworks are no good. There’s always been a debate about that, to see how far you can go.

MS

Actually what comes to mind are the ‘Altered Parliament House’ works. Those two works you painted when you were in Canberra. You were there during the dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975. They’re powerful paintings which are silkscreen and oil. Can you tell me a bit about that time?

‘Altered Parliament House I’ (1976) Synthetic polymer paint and oil screenprint on canvas Collection: National Gallery of Victoria

JS

I was in Canberra at the ANU for a couple of years. What do they call it? Creative Arts Fellowship. They gave me a studio. Students were supposed to come and listen to your wise words but nobody turned up so it was a very easy job (laughs). And a very interesting period because at that time the Whitlam Government was introducing Medicare. I used to go to Parliament House and sit listening to Question Time. I’d wander up there out of c