McCarthyism's Long Shadow

Description

It was 1954. Millions of Americans sat glued to their television sets as Senator Joseph McCarthy, once the most feared man in Washington, was humiliated during the Army–McCarthy hearings. “Have you no sense of decency, sir?” the famous rebuke rang out, and the chamber fell silent. For many, it was the moment the fever broke, when the republic seemed to reawaken from a nightmare of suspicion and silence. Yet the deeper story of McCarthyism is not about one demagogue brought low, but about the unsettling ease with which free people turned against the very liberties they had so recently celebrated as the essence of their national identity.

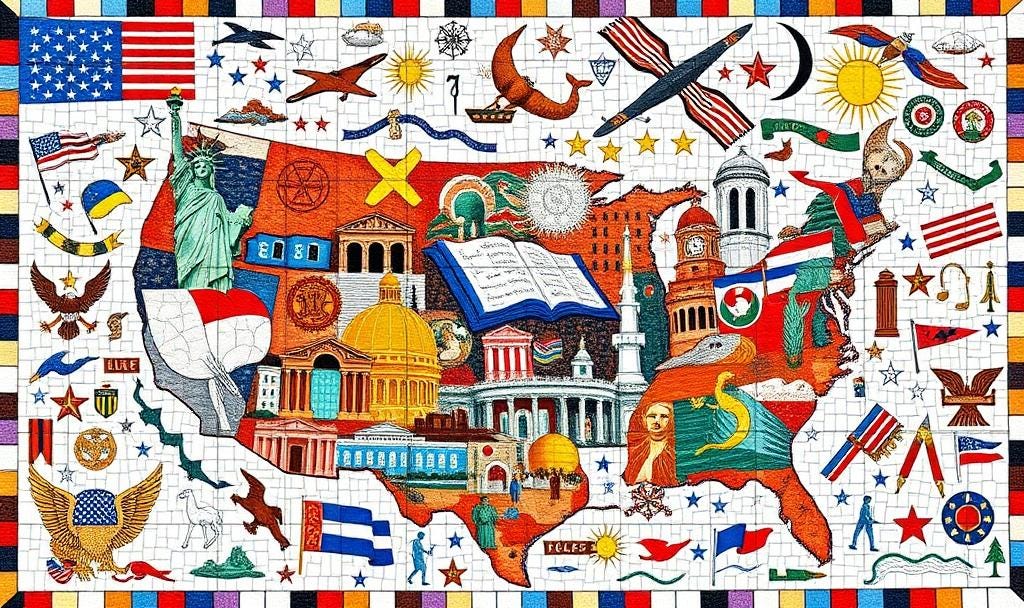

The United States, born of a revolution against tyranny and consecrated in the Bill of Rights, prided itself as the world’s beacon of liberty. And yet, within a few years of victory in World War II, it constructed elaborate loyalty programs, compelled citizens to sign oaths renouncing ideological sins, and allowed neighbors, colleagues, and artists to be branded “un-American” for the smallest hint of dissent. How could the land of Jefferson and Lincoln come to mirror, however faintly, the authoritarian systems it opposed abroad?

The answer lies in the dynamics of fear, power, and political expediency. The early Cold War was not simply a foreign policy conflict; it was an internal reckoning about who counted as “truly American” and how far the government could go in policing thought. The atomic bomb in Soviet hands, the “loss” of China, and the bloody stalemate in Korea stoked anxieties of betrayal from within. Political entrepreneurs seized the moment, weaponizing patriotism into suspicion, and suspicion into purge. Congress, the FBI, universities, Hollywood studios, and entire professions became arenas where liberty was curtailed in the name of protecting it.

But repression did not end with McCarthy’s downfall. The apparatus of surveillance and suspicion outlived him, shaping the boundaries of dissent for decades. And just as telling, the backlash against this era, expressed in the civil rights marches, student uprisings, and cultural revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s, was fueled by a generation determined never again to live in silence. McCarthyism was a wound and a catalyst. It scarred the republic, but it also provoked the most far-reaching reassertion of freedom in modern American history.

This essay asks a simple but disturbing question: why do free societies turn against their own freedoms? By tracing the rise, practice, and long shadow of McCarthyism, we can glimpse the fragility of liberty, and understand how American democracy, even in its most fearful moments, carries within it both the seeds of repression and the potential for renewal.

Seeds of Suspicion: The Cold War Domestic Context

The fear that gripped the United States in the late 1940s and early 1950s did not appear out of nowhere. To understand McCarthyism, we must first place ourselves in a world that seemed, to many Americans, to be unraveling.

Only a few years earlier, the United States had emerged from World War II as the undisputed leader of the “free world.” It had defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, possessed the world’s strongest economy, and held a monopoly on the atomic bomb. Americans believed they were living in a moment of triumph, with their ideals of liberty and democracy set to guide the world. Yet within a very short span of time, that sense of security collapsed into dread.

The Soviet Union, once a war ally, quickly became the United States’ primary adversary. In 1949, the Soviets shocked Washington by detonating their own atomic bomb, ending the U.S. monopoly on nuclear weapons years earlier than expected. That same year, China, the most populous country on earth, fell to Mao Zedong’s Communist Party, which American officials framed as a catastrophic “loss.” And in 1950, North Korea, backed by Moscow and Beijing, launched a surprise invasion of South Korea, pulling U.S. troops into a brutal war on the Korean Peninsula. To many ordinary Americans, it seemed as though communism was advancing everywhere, and that America’s survival was suddenly at stake.

But there was another, deeper anxiety: the possibility that America’s enemies were already inside the gates. The idea of “enemies within” became a powerful narrative. If China could “fall,” perhaps it was because of traitors in the State Department. If the Soviets could develop an atomic bomb so quickly, perhaps it was because spies had handed them secrets. The infamous case of Alger Hiss, a former high-ranking State Department official accused of being a Soviet agent, and the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, executed for passing atomic secrets to Moscow, cemented the fear that betrayal was not just theoretical, it was real.

The government’s own policies amplified this climate of suspicion. In 1947, President Harry Truman, himself a Democrat and often accused of being “soft” on communism, launched a sweeping Federal Employee Loyalty Program. This required government workers to prove their loyalty and allowed officials to investigate, even dismiss, employees suspected of “subversive” ties. No actual evidence of espionage was necessary. Mere association with the wrong organization could cost a person their livelihood. It was the first nationwide attempt to institutionalize loyalty screening, and it set the precedent that political orthodoxy was now a condition of employment.

These measures were not isolated. They reflected a larger cultural mood: Americans had learned to conflate unity with safety. To disagree, to dissent, to appear different in thought or association was suddenly dangerous. It was not just a matter of politics but survival. This atmosphere of fear and conformity prepared the ground for McCarthy’s meteoric rise. When he claimed that communists had infiltrated the government, he was not inventing a new fear. He was tapping into anxieties already deeply rooted in the American psyche.

The Rise of McCarthy and Political Opportunism

When Joseph Raymond McCarthy entered the national spotlight in 1950, he was hardly a household name. Born in 1908 on a Wisconsin farm, he rose from humble origins to study law, practice briefly, and then enter politics. During World War II he served as a Marine Corps officer in the Pacific, earning the nickname “Tailgunner Joe” for his combat flights, though even this part of his biography was later revealed to be heavily embellished.

By 1946, McCarthy was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Republican and his fortunes changed in February 1950, when, at a Republican Women’s Club speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, he claimed to have a list of 205 known communists working in the State Department. The number itself shifted in his later retellings, but the headline-grabbing claim electrified audiences. At a moment when Americans were already fearful of betrayal within, McCarthy offered a simple, dramatic answer. The enemy was not just abroad, it was in Washington, and he alone was brave enough to expose it.

McCarthy rarely produced verifiable evidence, but his accusations were crafted in ways that forced others to prove their innocence. This inversion of justice, where suspicion itself became condemnation, was enormously powerful in the climate of the early Cold War.

Several factors amplified McCarthy’s rise:

* Institutional timing: The Republican Party, out of power since the 1930s, was hungry for a wedge issue against Democrats. McCarthy’s accusations allowed them to portray Truman’s administration as weak and compromised.

* Media dynamics: Newspapers and, increasingly, television carried McCarthy’s dramatic charges into living rooms across America. For journalists chasing headlines, McCarthy’s bombast was irresistible.

* Bureaucratic allies: J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI shared McCarthy’s zeal for rooting out communists, and though Hoover disliked McCarthy personally, the FBI’s surveillance programs lent credibility to the atmosphere of suspicion.

By the early 1950s, McCarthy had turned his Senate committee into a stage for televised interrogations. Careers were destroyed, reputations ruined, and institutions, from the State Department to the Army, were paralyzed by fear of his investigations. McCarthy had no grand strategy, but he wielded fear like a weapon, and in an America unsettled by global shifts, fear proved a potent political currency.

The Machinery of Fear

McCarthy may have provided the spark, but the firestorm of the early 1950s was fueled by forces much larger than a single senator. Fear of communism seeped into the very fabric of American institutions, political, cultural, and social, creating an environment where liberty was curtailed not by a dictator’s decree but through countless small acts of compliance, intimidation, and silence. What emerged was not an authoritarian state imposed from above but a self-reinforcing culture of suspicion, in which ordinary citizens and powerful institutions alike learned to police thought as well as behavior.

One of the strongest tools was the loyalty oath. Following President Truman’s Federal Employee Loyalty Program of 1947, thousands of government workers were required to affirm that they had no ties to “subversive organizations.” The practice soon spread. State governments, universities, and even local school boards adopted their own loyalty requirements. The University of California became infamous for demanding that its faculty swear an oath renouncing communism. Professors who refused, not because they were communists, but because they objected to political tests as a matter of conscience, were dismissed. Freedom of thought itself was transformed into a liability; to question the oath was to invite suspicion.

The entertainment industry became another frontline in the battl