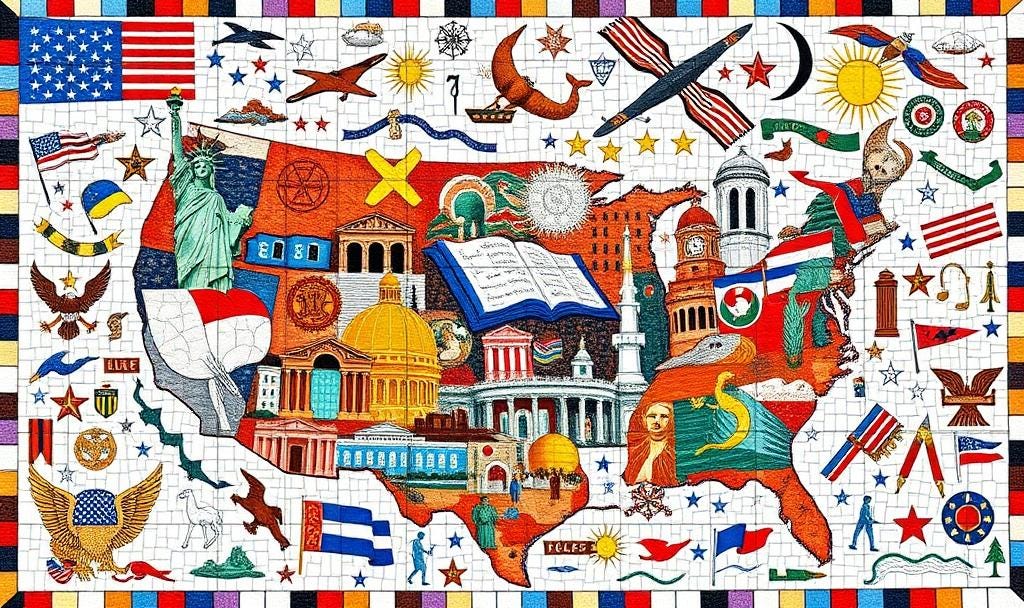

The Great America: 250 Years of Reinvention

Description

Two hundred and fifty years is a blink in the span of human civilization. Empires have risen and fallen over centuries; religions have endured for millennia. Yet in that quarter of a millennium, the United States compressed more transformation into its history than perhaps any other society. What makes the American story remarkable is not stability or continuity, but turbulence, risk, and reinvention. Greatness in America was never about being perfect, nor about being “great again.” It was about staying forever young, propelled by institutions strong enough to contain conflict and open enough to reward ambition.

From the beginning, America was a society that treated failure differently. In Europe, a bankrupt merchant or failed adventurer carried disgrace for life. In America, bankruptcy was a setback, not a sentence. Laws were forgiving, mobility was real, and newcomers found second chances. Alexis de Tocqueville marveled in the 1830s that Americans launched into trade “as if success or failure had no influence on their future condition.” That tolerance of risk created a culture where turbulence became the price of progress.

Alexander Hamilton understood this. Born illegitimate in the Caribbean, he arrived in New York as an outsider with nothing but ambition. As Treasury Secretary, he built the scaffolding of American capitalism: a funded national debt, a national bank, tariffs, excises, and support for industry. His aim was not merely solvency but credibility — to make the republic a trustworthy borrower so that capital would flow. He wrote that “a national debt, if it is not excessive, will be to us a national blessing.” To his critics, this sounded reckless. To Hamilton, it was nation-building through trust, a system where finance served opportunity, not just inheritance.

Thomas Jefferson, Hamilton’s rival, imagined something different: a republic of yeoman farmers, free from the corruption of banks and cities. He saw Hamilton’s system as a seed of oligarchy. Yet his agrarian ideal was paradoxically sustained by Hamilton’s finance. Without credit, infrastructure, and markets, farmers would remain poor and isolated. Jefferson purchased Louisiana and expanded opportunity, but his farmers needed Hamilton’s canals and credit to prosper. Thus, from the start, America fused two contradictory visions — agrarian egalitarianism and financial capitalism — into a restless hybrid that could adapt.

Europe, by contrast, clung to feudal residue. The revolutions of 1848 demanded liberal reform but were crushed by monarchs and aristocrats. Industrialization advanced, but under dynastic control. America was an empire too, but one without emperors. Its legitimacy rested not on bloodlines but on constitutional order. Politics was fiercely partisan, sometimes violent, but elections, not thrones, conferred power. The Civil War tested this experiment. Slavery was the deepest contradiction, but secession also revealed a clash of economic visions: an agrarian system bound to coerced labor versus an industrial, capitalist republic. The Union’s victory destroyed the last vestiges of feudalism and ensured that America would be defined not by cotton but by industry, migration, and knowledge.

By 1900, the United States had overtaken Britain as the world’s largest economy. The Gilded Age produced vast fortunes — Rockefeller in oil, Carnegie in steel, Vanderbilt in railroads. Inequality was immense, but unlike Europe, it was fluid rather than permanent. Yesterday’s factory worker could become tomorrow’s shopkeeper. The son of an immigrant could rise into business or politics within a generation. Railroads — more than 170,000 miles laid between 1871 and 1900 — opened markets, lowered barriers, and spread opportunity. Inequality was real, but it was not destiny. America’s mobility made the risk worth taking.

Technology amplified this dynamism. Railroads shrank distance. The telegraph and telephone collapsed time. Electricity transformed industry and daily life. Automobiles replaced horse-drawn carriages. Each innovation created new fortunes and destroyed old ones. This was not incremental change but what Joseph Schumpeter later called “creative destruction.” Standard Oil looked unassailable, until new energy and new firms displaced it. Carnegie’s empire seemed permanent, until chemistry and new materials shifted the frontier. In America, permanence was the illusion; disruption was the rule.

The Great Depression challenged this ethos. The crash of 1929 was not just a financial panic but a collapse of confidence in capitalism itself. Breadlines stretched across cities, banks failed, unemployment soared. Critics said laissez-faire had run its course. Europe turned to socialism, fascism, and corporatism. Yet America did not abandon capitalism. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal built scaffolding — Social Security, deposit insurance, public works — but it did not create a European-style social democracy. The aim was not to lock society into stability but to buy time for capitalism to heal. And heal it did, through innovation. Even in the depths of depression, America produced advances in aviation, radio, automobiles, and medicine.

World War II confirmed the lesson. Before the war, America’s army was smaller than Romania’s. Its strength lay not in troop numbers but in industrial capacity and engineering ingenuity. Within months, Detroit switched from cars to tanks and bombers. Boeing and Douglas scaled aviation to new heights. Bell Labs advanced radar. The Manhattan Project built the atomic bomb. This was capitalism at full throttle: not central planning, but urgency harnessed to flexibility. America won the war not by being the biggest army, but by being the most creative problem-solver.

From 1945 to 1973, the “Golden Age of Capitalism” saw productivity surge, wages rise, and the middle class expand. The GI Bill opened universities to veterans and made homeownership widespread. Highways, suburbs, and consumer culture flourished. Inventions like transistors, computers, and space technology reshaped society. For many Europeans, prosperity seemed to come from welfare states. In America, the deeper driver was innovation. Risk, mobility, and reinvention made the middle class possible.

Globally, America anchored a new order. At Versailles, Woodrow Wilson’s principles reshaped international law. At Bretton Woods, the dollar became the world’s anchor currency. Even after gold convertibility ended in 1971, the dollar’s credibility held. Washington built institutions — the IMF, World Bank, NATO, GATT — but its true advantage lay in its private sector and financial depth. Wall Street became the clearinghouse of global capital; American corporations designed and managed global supply chains. The United States was not the largest exporter, but it was the orchestrator of value creation.

As manufacturing shifted abroad, America became the first true post-industrial society. Deindustrialization looked like decline to some, but it was actually reinvention. The country moved up the value chain: from making goods to designing them, branding them, financing them, and selling them to the world. McDonald’s exported not just hamburgers but a model of management and supply chains. Procter & Gamble exported detergents and the science of marketing. Apple created an ecosystem of design in California and assembly in China, proving that value lies not in factories but in knowledge and coordination. Nvidia’s chips today underpin the artificial intelligence revolution, another American-led transformation.

Silicon Valley embodied the cultural difference. Failure was not shame but experience. Venture capital funded untested ideas. Universities like Stanford and MIT incubated startups. Out of this ecosystem came Microsoft, Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook. Europe had engineers, Japan had factories, China had labor. But only America combined risk-tolerant culture, deep finance, world-class universities, and openness to talent. That is why the Information Revolution, like the Industrial Revolution before it, was American-led.

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 seemed to mark the “End of History.” Communism had collapsed; liberal democracy and capitalism looked universal. Yet America’s story was not one of unchallenged triumph. Polarization grew as some regions prospered while others fell behind. The 9/11 attacks reframed security around non-state threats. Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq showed the limits of military power in remaking societies. China offered an alternative model through its “Beijing Consensus,” financing infrastructure and state-led growth across the Global South. But this model produced dependency, corruption, and backlash when projects faltered. It lacked legitimacy, the very foundation Hamilton had prized.

Today, America faces a paradox. Its government is often reluctant to act as an empire. Fiscal strain and cultural instincts push Washington inward. Yet America remains the greatest beneficiary of globalization. Its true strength lies not only in government but in its decentralized networks of influence. Apple, Nvidia, Microsoft, and Google design the platforms of the digital age. Wall Street clears global capital. Harvard, MIT, and Stanford train leaders who carry American methods worldwide. Hollywood, Netflix, and the NBA project culture into billions of homes. Civil society — NGOs, foundations, churches, think tanks — promotes openness and pluralism. No other society possesses such an interlocking ecosystem of influence.

This is why the United States remains exceptional. Its genius has never been in perfection but in reinvention. Its capitalism is turbulent, but turbulence is the price of mobility. Its politics are polarized, but institutions endure. Its inequalities are real, but they are not destiny. America’s greatness is not a thing to be regained. It is the continuin