My Favorite Year

Description

Wit and Wisdom

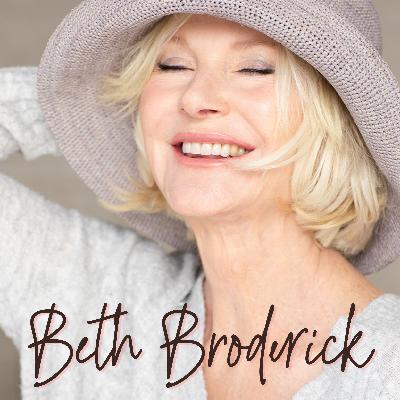

by Beth Broderick

“1954 was my favorite year,” the voiceover that narrates the start of the classic old film “My Favorite Year” declares. “In 1954, a Buick looked like a BUICK,” the rich, heavily New York-accented voice continues, as the camera lingers on the grille of a classic Buick sedan. “Nowadays a Buick looks like a Ford, which looks like a Pontiac,” he laments. (I am paraphrasing, but you get the gist.)

He had a point. Today’s cars are not nearly as ornate or elegant as the one depicted in the movie, but they are equipped with life-saving devices not available then. One has a better chance of surviving a collision in one of our modern vehicles. They may be lackluster to look at, but they are more than machines. They are giant computers on wheels, capable of parking themselves, detecting raindrops, displaying live satellite images of traffic on your dashboard. So, take that, 1954! We are not as sightly up here in the 2000’s but we are capable of some serious whiz-bangery. (Really, though, something should be done about those hideous Tesla trucks. We should have known Elon was getting wiggly when he approved those contraptions. An eyesore on the roads.)

When it comes to years, one is tempted to play favorites. In my youth, I was inclined to make definitive statements about such things.

“This year sucked!!” I might have said in response to career frustrations, or personal turmoil that had been a feature of the month’s past. I am sure that in hindsight there was more nuance to that narrative, but time felt so plentiful, life so well guaranteed, that it was easy to label a year that didn’t go entirely my way as a bad one.

That feels ungrateful now, in light of the dwindling number of years available to me. Mom made it to 83 … not bad … until I realize that number is less than two decades away for me. Not even 20 years left if my fate follows hers. Dad made 93, which gives me a bit more breathing room, though he went that distance with some considerable handicaps in the fourth quarter, most notably the complete loss of his eyesight. Macular degeneration runs in the family. I am swallowing those lutein vitamins like candy and crossing every digit, but the possibility looms.

I look back on even the toughest, leanest years of my life with fondness and appreciation.

The year I entered the American Academy of Dramatic Arts was complicated, wonderful and terrible in equal measure. I rented a room near the school in Pasadena from an older woman named Mrs. Snyder. She was in the process of learning Braille as her vision was dimming and she did not want to be caught off guard. Something to consider there, now that I am remembering it. I was 16 years old and lied my way into a waitress job at Bob’s Big Boy. The hours were long as I raced from class to work, but there was a sense of discovery at every turn and, even with all of the doing, there was a respite from the chaos and violence of my mother’s home.

Mrs. Snyder worried that I worked too hard. She would wash out my uniforms by hand and hang them to dry in front of the oven, which was always on. In hindsight that was a bit unwise, but I was touched by her care and concern. She would make oatmeal and save a portion for me on the stove. I politely tried to eat it, though it had usually congealed into a thick paste by the time I got home. I loved her and I loved school, though I was often sleep-deprived and winging it, sneaking in study time on my breaks from work. For the first time in my life, I felt like I was where I was supposed to be.

My rare time off was spent exploring Pasadena, the oldest city in California. There were a few tiny, old-timey buildings on Colorado Blvd. which offered counter service for breakfast. There were no more than 5 or 6 stools in each, but wait times were short and the food was hearty if uninspired. There were bookstores and old movie houses and a host of good cheap restaurants, my favorite of which was “Pie ’n Burger,” a local legend of a joint, still in operation today, which serves only those two things, good burgers and great pie.

There were two engineering students living next door and they dazzled me with their intellect and grown-man-ness. I can still smell the after-shave the taller boy wore. Whenever he stopped to talk to me, I nearly swooned. At school, I was exhausted and out of my league, as most of the other students were 20 and older, but I was determined to succeed. There was a tense moment or two or three, when the folks who ran the school somehow found out that I was only 16 years old.

“You will not make it here,” I was told. “You will want to leave, or we will have to ask you to leave… you are too young.”

The one sure way to get me to do something is to tell me that I can’t.

I begged and pleaded and pledged to work as hard as I could to earn the right to stay in class. I assured them that I knew I had what it took. They agreed to let me stay, but let me know that I was on notice. One slip-up and I would be out. I doubled down and won over most of my teachers with diligence. I have always been a confident test-taker, so I breezed through those without much effort. The administrators eventually backed off, and my shoulders started to go down.

One night I got home from a shift at the restaurant at about midnight. I threw on pajamas and got into bed, trying to get as much rest as possible before the alarm sounded at 6 a.m. I was drifting off when I suddenly bolted up. Something was wrong; I was sure of it. I made my way down the hall.

“Mrs. Snyder? Mrs. Snyder, is everything okay?” I looked toward the kitchen where the ever-burning oven remained on without incident, then I saw a beam of light under the bathroom door. I knocked and knocked, calling her name, but there was no answer. The door was open, so I pushed it in and saw her lying on the floor. She was immobile, but alive. She could not speak, and I did not know if she could hear me. I ran to the desk and searched for her daughter’s phone number and called her. She promised to send an ambulance. I did not know what to do, but I could not let my friend lie there on that cold floor. I was sure she must be freezing.

I ran to my room and grabbed the blanket and pillows from my bed, then raced to the bathroom. I covered her little body, then put her head on the pillow in my lap. I just sat there talking to her quietly and stroking her soft cheek. I knew in my bones that it would not be long.

Mrs. Snyder lingered for just three days. The daughter was furious. She blamed me for the whole situation, for not finding her mother sooner, for calling her first before dialing 911. I was immediately kicked out of the house and went on a mad scramble to find a place to stay so that I could finish out the year at school. I was devastated, but I pressed on.

There were 100 people in my freshman class. Only 25 were invited into the graduate year. I was one of those 25.

It was a tough year. It was terrible and wonderful and scary and awe-inspiring; all of the things that life can be rolled into one big, messy first foray into adulthood. Oh, and I lost my virginity somewhere along the way.

Like every year before it and since, it could not be described as either good or bad. It was fully lived and, as such, was both. It began as 1975 and ended as 1976.

A YEAR TO COME.

2025 was a bad year for a lot of folks in my industry. Production is down and has taken wages and work hours with it. What little filming there is, is often being shipped overseas where it can easily escape union oversight. The battle over the sale of Time Warner and its subsidiaries is being watched with great trepidation. There has been a relentless move toward corporate consolidation of the entertainment industry for decades now. The relaxation of our monopoly laws and political indifference to their enforcement has narrowed the number of employers to an ever-smaller group of big guns. A very few, very powerful folks now call all of the shots and own all of the mechanisms which distribute content to your screens.

Actors, hair and make-up artists, writers, directors, film crews, and teamsters are all suffering. It is an actual job that many of us have done for a very long time. Most are at a loss as to what to do, as things seem unlikely to rebound anytime soon. The 2024 rallying cry of “Stay alive till twenty five” has rung hollow; it seems in hindsight to have been laughably optimistic. This was not the year’s fault. 2025 did not ask to be painted with the brush of disappointment.

Some bad things happened and some good things didn’t, but I am not blaming the year itself. The year consisted of days counting themselves from one Sunday to the next, of months holding court with their bounty of birthdays and bat mitzvahs and graduations and then ceding ground to the next one, biding their time until it was their turn to be lived through once again.

For me, the frenzied activity of the holidays has given way to the tedium of tending to a seasonal cold. Winter has begun in earnest in Los Angeles, where the burnt wheat colors of our grasslands have flushed green with the recent rains. The hills are a deep emerald, offset by hues of olive and pine; the streets are washed clean by floodwaters. The new year will arrive in the midst of another big storm that is heading this way. 2026 will make a wet and wooly entrance, full of both menace and promise as “years” are wont to do.

I do not know what the year will hold in store for me, but I am grateful to herald its arrival, humbled by the opportunity to live it, eager to breathe it in.

Wishing you all the very best in the coming days, but you know … there are no guarantees, so hold on to your hats, ’cause anything could happen. It’s just a year, only a year in the life, but it is ours to behold…