Scientific Blind Alleys: Dietary Fat, Sugar, Freud, and Adler

Description

In science and medicine, the most dramatic explanations often grab headlines – but they can sometimes be wrong. Two classic examples are the mid-20th-century diet-heart hypothesis and early psychoanalytic theory. In the 1950s–60s, researchers convinced the world that saturated fat was the villain behind heart disease, leading governments and food makers to push low-fat diets. Meanwhile, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis – with its emphasis on childhood trauma and unconscious drives – dominated psychology, sidelining Alfred Adler’s more future-oriented ideas. In both cases, decades of public policy, clinical practice and cultural belief were shaped by a compelling but oversimplified cause. Over time we’ve learned these theories were misleading: sugar and other carbohydrates, not just fat, were fueling obesity and diabetes, and goal-driven therapies (like CBT and Adlerian “individual psychology”) often serve patients better than digging endlessly into the past. These stories remind us that early science can latch onto a single, dramatic cause and stay on it for decades, with far-reaching consequences.

Thanks for reading Bariatric Journal! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

1. The Fat Fallacy: Keys, Low-Fat Diets, and the Obesity Surge

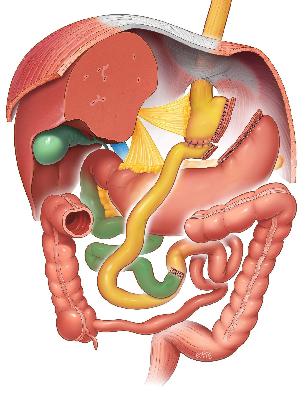

In the post-war era, heart disease was skyrocketing. A 1951 survey called body fat “America’s ‘primary public health problem’.” In 1952 President Eisenhower’s heart attack made heart disease a national crisis . Nutritionists scrambled to explain why. In 1958 Ancel Keys launched his famous Seven Countries Study – a large survey of heart disease risk factors – and emerged as the loudest voice blaming saturated fat. Keys famously concluded that “fat was to blame” for heart disease and that only a low-fat diet would reverse the trend . At around the same time, British researcher John Yudkin noticed that countries with high sugar intake also had high heart disease rates and argued that sugar (sucrose) was a major culprit .

Initially Yudkin even admitted both fat and sugar might play roles . But Keys was adamant that fat alone drove the epidemic. Yudkin later accused Keys of “cherry-picking” data to support his low-fat view . By the 1960s–70s, the idea “fat = bad” had won the day: public health guidelines and doctors told everyone to slash butter, eggs and meat fat out of their diets. The food industry rushed to replace fat with cheap carbs; low-fat products were sweetened heavily with sugar to taste good . In a sense, the sugar industry got what it wanted: by promoting the fat hypothesis, sugar became the “hidden” culprit (even as fat got demonized).

Over the same decades, obesity and related diseases exploded. US obesity rates more than tripled since the 1960s.

Globally the picture was similar. World Health Organization reports show adult obesity nearly tripled from 1975 to 2016 . By 2016 some 650 million adults (≈13% of the world’s population) were obese . If trends continued, models predicted over a billion obese by 2025 . In the US today roughly 42% of adults are obese , up from ~13% in the early 1960s . During these decades many Americans dutifully followed low-fat advice – eating fat-free cookies and high-sugar cereals – while gaining weight.

Why didn’t cutting fat stop the epidemic? Modern evidence suggests Keys’s theory was over-simplified. A growing body of research now points to refined carbohydrates and sugar (not fat) as major drivers of obesity, diabetes and heart disease. A 2023 review notes that clinical trials “could never establish a causal link” between saturated fat and heart attacks, and in fact concluded that saturated fats have “no effect on cardiovascular disease” or mortality . In other words, decades of guidelines capping fat intake are being re-evaluated. At the same time, sugar’s dangers have gained renewed attention. The World Health Organization now recommends cutting “free sugars” to under 10% of calories (5% ideal) because excess sugar intake promotes obesity and heart disease . In short, the dramatic focus on fat led us to ignore the growing evidence on sugar – and millions consumed low-fat/high-sugar foods that may have worsened weight gain and metabolic health.

This history wasn’t a conspiracy of ignorance – though industry influence played a role. In fact, internal documents reveal that the sugar industry actively paid for early research to downplay sugar’s risks. In the 1960s the Sugar Research Foundation funded Harvard researchers who published a landmark 1967 review in the New England Journal of Medicine, concluding that lowering cholesterol (by cutting fat) was the only dietary fix . That review conveniently dismissed evidence implicating sugar . More recently, uncovered archives show the industry had privately sponsored this work to protect its product . The result: public health messages and food policies were skewed. As one nutrition historian observes, the 1960s–70s saw an obsession with “single nutrient” explanations (good fat vs. bad fat) while “overall attention unquestionably focused on fat” , largely ignoring sugar.

Thanks for reading Bariatric Journal! This post is public so feel free to share it.

In summary, the Keys era pressed a simple, dramatic culprit (fat) for complex diseases, with huge fallout: low-fat nutrition guidelines, sugar-laden diets, and a continuing obesity epidemic. Only after decades did researchers start correcting course. Modern reviews now urge a balanced view: replace refined carbs with whole foods, and recognize that sugar is a prime factor in today’s health crisis . This reversal shows how a powerful but narrow theory can mislead for generations.

2. Freud’s Empire and the Overlooked Adlerian Way

At roughly the same time diet fads were taking hold, psychology was under the sway of another grand narrative. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), an Austrian neurologist, founded psychoanalysis and became one of the century’s most famous thinkers. His revolutionary idea was that unconscious drives and childhood experiences – especially repressed sexual and aggressive impulses – shape all behavior . In the late 1800s and early 1900s Freud developed techniques like free association and dream analysis to uncover these hidden conflicts . His model of the mind (id, ego, superego) and notions like the Oedipus complex became deeply influential. As a historian notes, Freud’s impact on psychology was so huge that “throughout his life… he worked fervently… His impact on shaping the theoretical and practical approaches to the human mind… cannot be understated” . By mid-century psychoanalysis was the go-to theory for mental illness: many therapists believed that resolving past traumas was the key to treating depression, anxiety, neuroses and more.

But Freud was not alone. Among his early circle was Alfred Adler (1870–1937). Adler co-founded the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society with Freud, but in 1911 he broke away from Freud’s theories to form “Individual Psychology” . Adler rejected Freud’s emphasis on sexual drives and inner conflict. Instead, he saw people as primarily goal-directed and motivated to achieve significance and social connection. Adler focused on concepts like “striving for superiority” and “social interest,” believing that we compensate for feelings of inferiority by setting future goals and cooperating with others. For example, Adler stressed empowering children – helping them build confidence and tackle life tasks – rather than endlessly dissecting their childhood guilt or fear . He famously said that healthy growth comes from feeling connected and useful in a community, not from reliving past injuries.

Despite Adler’s insights, Freud’s personality and followers dominated the field. In the 1920s–50s, psychoanalysis grew into a massive movement (with institutes, journals and popular culture references), while Adlerian ideas remained on the fringe. Adler’s own biography notes that when he lectured in the US in the 1930s, “his followers found substantial resistance from those who adopted Freud’s psychoanalysis” . In practice, most psychologists and psychiatrists were trained in psychoanalytic or psychodynamic models and viewed Freud as the towering figure of psychology. (Indeed, Freud was the most-cited psychologist of the mid-20th century .)

Over time, cracks appeared in the Freudian approach. Psychodynamic therapy (the modern descendant of Freud’s methods) emphasizes resolving past conflicts and unconscious motives . Patients sit in therapy for years, exploring childhood memories, dreams and slips of the tongue. Critics argue this can become self-defeating. The process is often very lengthy and expensive – a common complaint is that it “has faced criticism for its focus on the past and the length and cost of treatment” . Some therapists and patients found it too passive: rather than learning coping skills, patients were encouraged to keep reliving trauma. As a primer on psychotherapy notes, psychodynamic therapy can indeed help foster insight, but it does so by digging into old wounds rather than building new strategies .

By the late 20th century, new schools of therapy were rising. Behaviorism (think Skinner, Watson) and then Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) turned attention to present thoughts and behaviors. Aaron Beck’s CBT (1960s onward) was evidence-based and short-term, aiming to change destructive thought patterns now rather than uncover hidden past drives. Today CBT is “extensively researched” and widely recommended – in fact it is regarded as the “gold standard” of psychotherapy in modern guidelines . It treats anxiety, depression and even trauma effectively by targeting current thinking and habits. Likewise, solution-focused and humanistic therapies emphasize future goals, personal agency and strengths. Even forms of psychodynamic therapy have evo