Self-Inflicted Civilizational Collapse — An Ancient Climate Story

Description

Dotting the walls of the red sandstone canyons all across the Four Corners region of the southwestern United States (where Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico meet), high up on the vertical cliffs, you can see the ancient ruins of countless cliff dwellings and granaries, big and small, perched on seemingly impossible narrow ledges, sometimes hundreds of feet up off the valley floor where the slip of a single footstep means certain death. No sane individual that loves their children would voluntarily choose to raise a family in a place like that.

And yet, for more than a century, the refugees of a failing civilization did just that.

And then they mysteriously disappeared from the region altogether, leaving behind a devastated ecosystem that even today, more than 700 years after their passing, still hasn’t recovered.

Their story is a lesson to us all — and not for any of the reasons that you typically hear on the six o’clock news.

For centuries, the Anasazi or Ancestral Puebloan culture of the Southwest divided their time between the adobe pueblos and agricultural fields that they built among the pinyon pine and juniper woodlands up on top of the cooler mesas and growing crops and building pueblos alongside reliable water sources down on the hot canyon floors. But then, in the 12th and 13th centuries, all across the region, something big changed to cause these ancient people to start moving into these precarious stone hovels perched on the edge of certain death, half-way up between the canyon bottoms and the rim of the mesas above.

What made them abandon their earlier customs to adopt such a perilous new way of life?

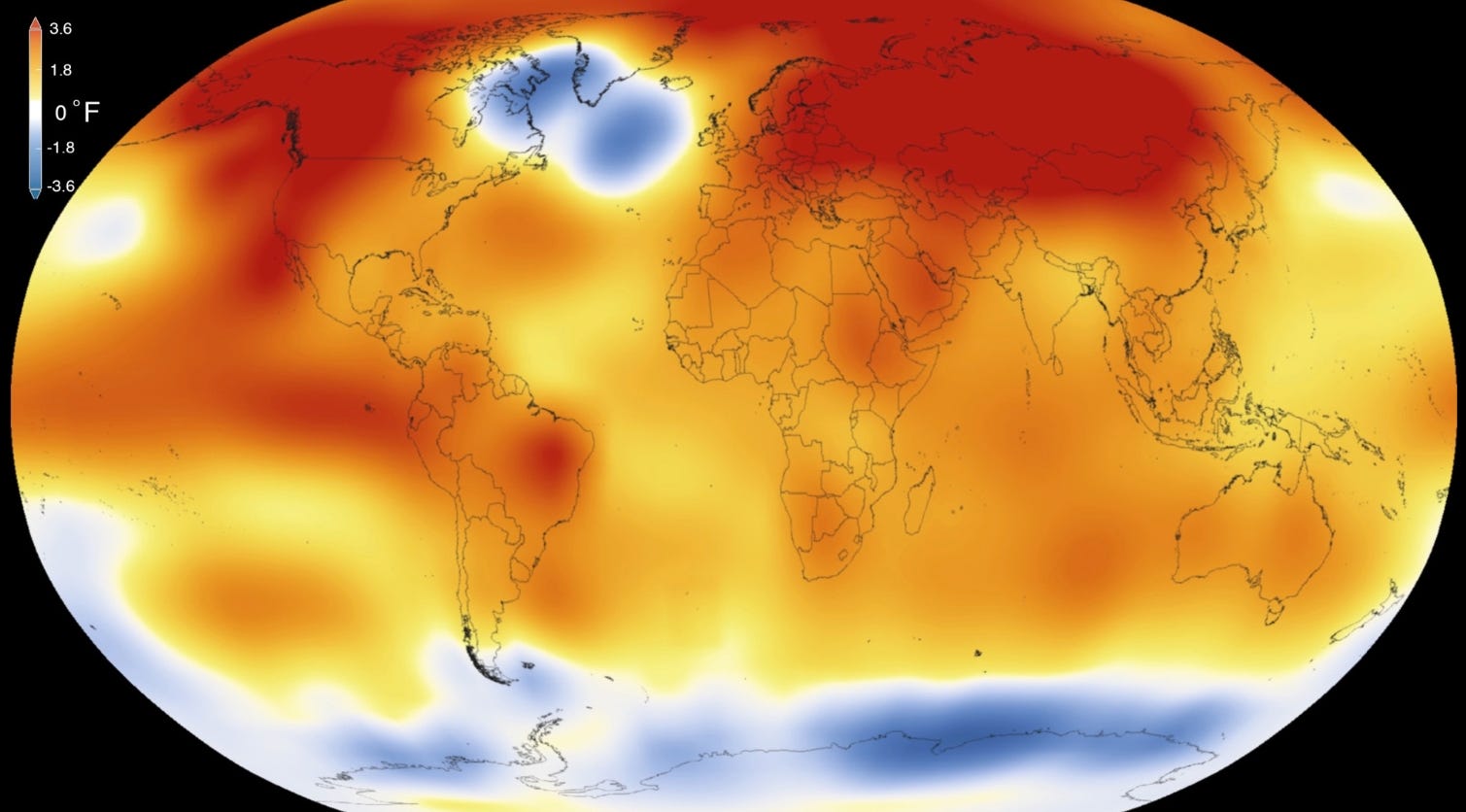

The simplistic but only partially true explanation is that the climate changed. Two brutal multi-decadal megadroughts in the 12th and 13th centuries triggered a collapse of the cultures and traditional ways of life across the entire region — the geographic extent of these two droughts is shown in yellow (12th century) and red (13th century) in the chart below.

As the droughts took their toll, the entire previously relatively peaceful region was plunged into decades-long conflict, war, and extreme violence (there’s even archaeological evidence for torture, cannibalism (both ritual cannibalism and cannibalism motivated by starvation), and vicious attacks that destroyed entire villages), all of which led people to seek refuge in increasingly inaccessible places to stay out of reach of their hungry enemies.

Mesa Verde in the Colorado portion of the Four Corners region is arguably the most famous cliff dwelling on the North American continent. After living primarily on top of the mesas for over 600 years, sometime in second half of the 12th century during a period of intense social and environmental instability, the Ancestral Puebloans turned Mesa Verde into a massive city. At its peak, Mesa Verde was home to many thousands of people. And yet, after nearly a century of intense occupation, by 1285 Mesa Verde was completely abandoned. The Ancestral Puebloans migrated out of the region altogether — their scattered modern-day descendants are the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, Tewa and other Pueblo peoples.

The second most famous Ancestral Puebloan archaeological site in the region (and arguably the most impressive example of ancient architecture north of the Mexican border) is Chaco Canyon in the New Mexico portion of the Four Corners region (shown in the image below). It is the largest ancient architectural complex ever built on the North American continent north of the Mexican border prior to the 19th century. By its sheer size alone, it was clearly once the core of a very large civilization. Some of its massive buildings were more than 5 stories tall and contained up to 800 rooms!

This extraordinary site at the bottom of Chaco Canyon served as the major cultural center for all Ancestral Puebloans across this vast region for more than 600 years! It was the central hub of a sphere of influence that spanned across more than 90,000 square miles (and area larger than Ireland!) and even included a huge network of roads, some more than 30 ft wide, linking together the other Great Houses across the region (more than 150 of them have been found so far), all of which are connected back to Chaco Canyon by these roads. And yet, Chaco Canyon was abandoned during the first of these two megadroughts, in the second half of the 12th century, before Mesa Verde was built and just as the mass shift to cliff dwellings in the region took place.

At its peak, Chaco Canyon’s vast building projects were supported by huge rock quarries where they harvested their sandstone blocks. They also hauled massive timbers to the site from as far as 110 km away — archaeologists estimate that more than 200,000 large timbers were transported to the site between 850 and 1200 AD using only human power (no small feat in both manpower and organizational planning considering that this is at a time before either the wheel or horses were introduced to the continent).

And the astronomical alignments reflected in their building architecture captured lunar and solar cycles that would have required generations of meticulous observations. And yet, the crippling 50-year megadrought that began in 1130 led them to abandon their canyon altogether. By 1150, more than a century before Mesa Verde was abandoned, Chaco Canyon was already an empty ruin— the central node of Ancestral Puebloan civilization collapsed during the first of those two megadroughts.

The abandonment of Chaco Canyon was accompanied by significant changes in religious beliefs and religious practices all across the Southwest. However, what emerged was not replacement by a new religion or a new culture but rather a fracturing of a large, centralized religion into less formal and more local clan-based rituals as the unifying religious authority collapsed. The large circular kivas (a.k.a. ceremonial rooms), like the enormous kiva shown at Chaco Canyon in the image above, were replaced by much smaller, less formal kivas scattered across the region. Even the rock art in the region evolved to show new motifs and evolving spiritual concerns, even as burial practices became much simpler.

In sum, we get a picture of a collapsing complex civilization that fractured into desperate and increasingly hostile rival clans, which reverted to a much simpler way of life. And where once all these people were united as a single, stable, relatively peaceful, and cooperative culture capable of building vast architectural projects and hauling timbers across the entire region, now they lived in fear of one another even as the ecosystem that once sustained them began to collapse all around them.

If you’ve followed the late Andrew Cross’ Desert Drifter channel on YouTube, which explored many of these ancient archaeological sites across the Southwest, you’ll know just how extreme the living conditions were in some of these ancient cliff dwellings that were built during that tumultuous period. These ancient people were clearly pushed to the very brink of survival and lived in terror of other clans in the region — these abandoned cliff dwellings truly capture a snapshot in time during the last stage of civilizational collapse before the region was abandoned altogether.

Complicating it all is that Athabascan tribes (ancestors of the Navajo, Apache, etc) also migrated into this region from the north, though most archaeological evidence suggests that the bulk of this southward migration of newcomers only reached the Southwest in the 1300s and 1400s (some archaeologists place the date as late as 1450 AD) long after both Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde were abandoned and after the Ancestral Puebloan population in the region had already collapsed and most had fled. So, the violence that drove the Ancestral Puebloans into their cliff dwellings was “home-grown” — the consequence of the internal chaos unleashed by a collapsing previously-centralized civilization — and is not readily blamed on the arrival of outside tribes.

But while the mega-droughts of the 12th and 13th centuries undoubtedly served as the trigger for destabilizing Ancient Puebloan culture, once you dig deeper into the geological and archaeological research (as we are about to do), you quickly discover that there is much, much more to this story.

The victims of this climate disaster were also simultaneously the chief architects of the disaster that destroyed their civilization — their impact on their local ecosystem turned what otherwise would have been just another dry period within the never-ending cyclical climate patterns of the region into an existential crisis that destroyed not only their civilization but also permanently degraded an ecosystem that was previously perfectly adapted to weather these kinds of megadroughts into the dry, fragile, brittle ecosystem that persists in the region even today.

As shocking as it may be to anyone who has toured the extraordinary wilderness of Utah’s canyonlands, although geology created these canyons, everything else about this brittle landscape was created over centuries by the mismanagement of ancient human hands.

The lessons from that long-forgotten story — about the evolution of civilization, about soil and deforestation, and about the complex forces that shape our climate and either keep our ecosystems healthy or destroy them — are all still very relevant to our own era. As Charles Lyell (the “father of geology”