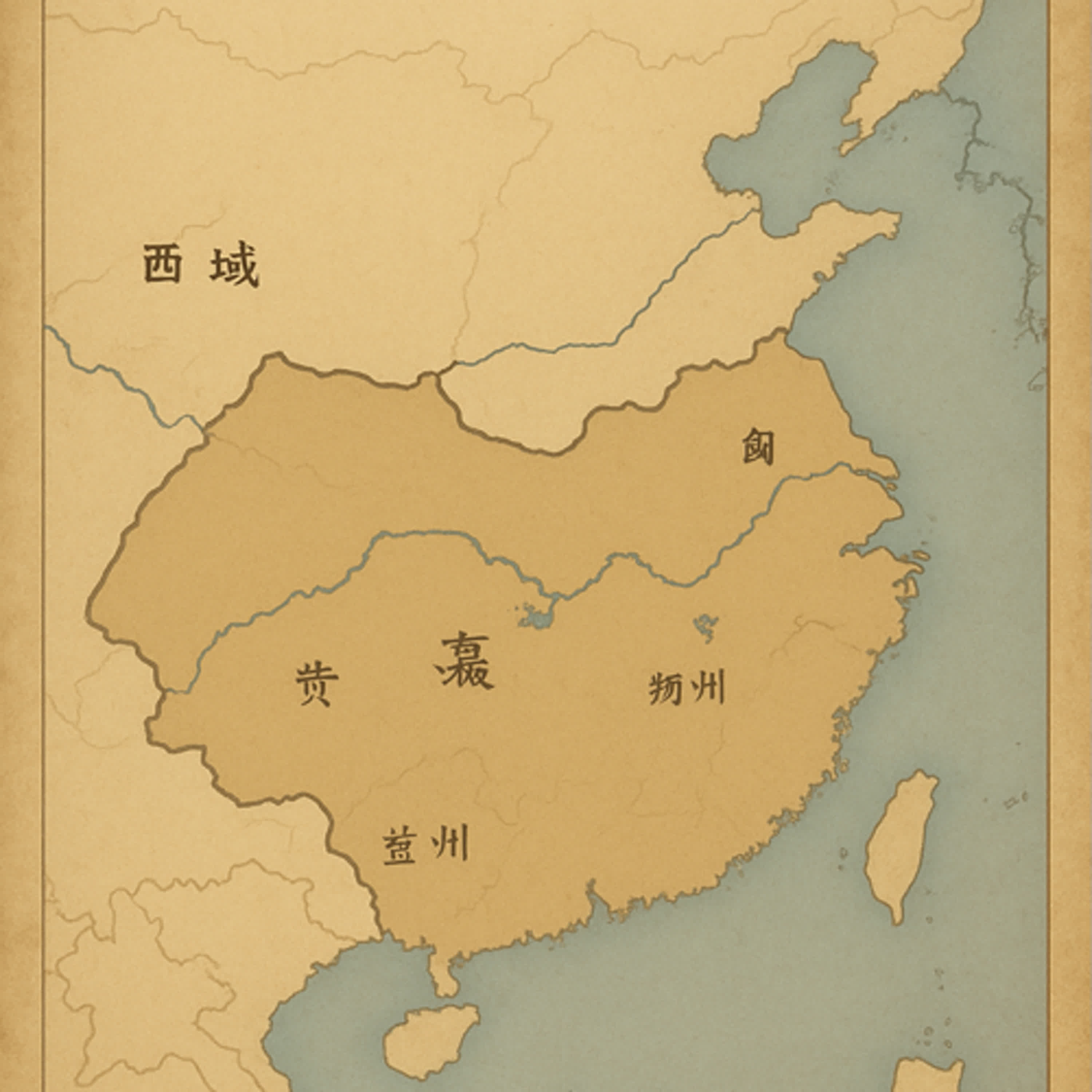

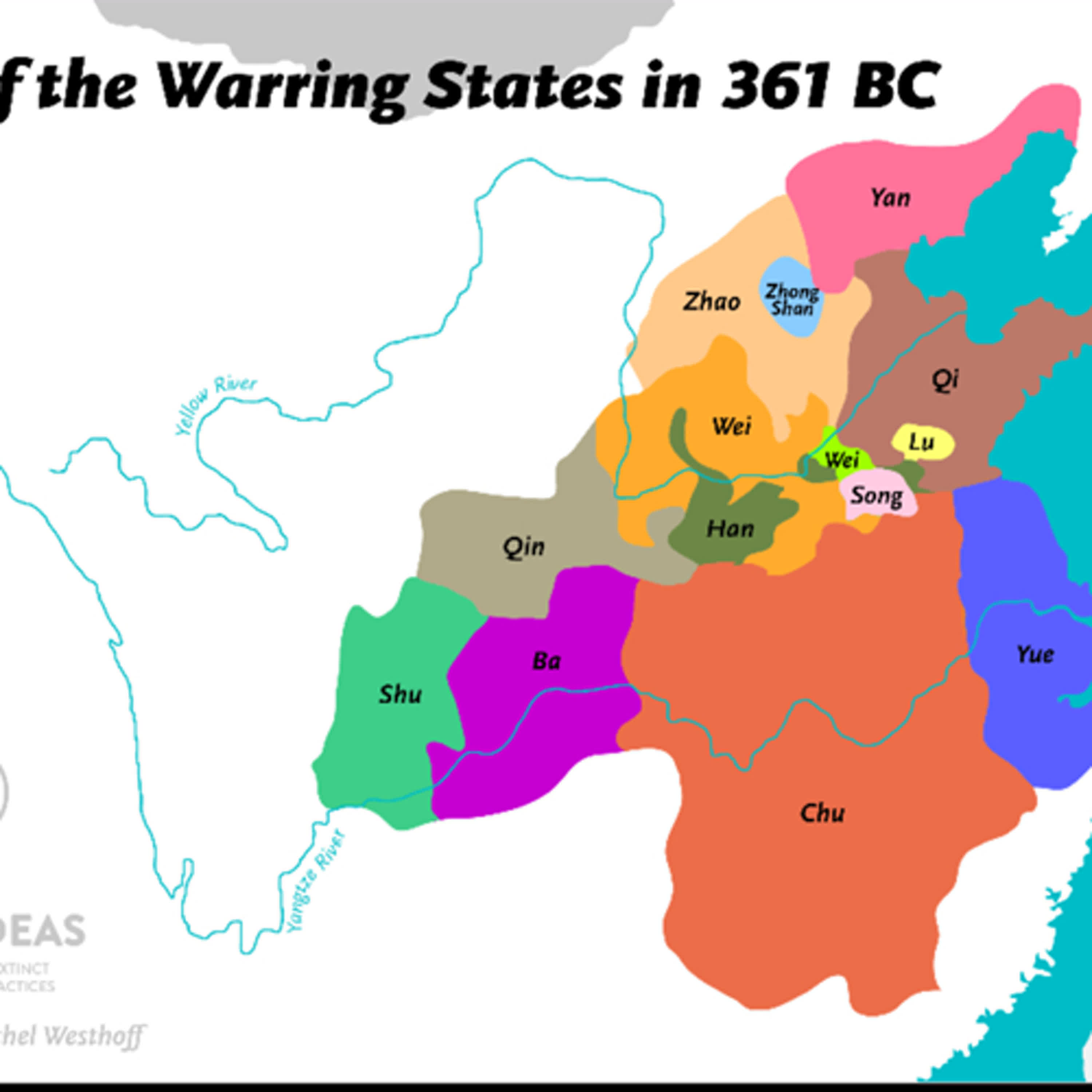

The Chaotic Warfare of 2nd & 3rd Century China

Description

Today, I’d like to talk about the second major event described in the 7th book of Mr. Bo Yang’s Tongjian Jishi Benmo—the turbulent struggle for power in the late Eastern Han dynasty. Many of you may already be familiar with the wars, the rivalries, and the rise of various warlords during that period. So rather than retelling the same historical stories, I’d like to approach this event from a different angle—the perspective of mindset and psychological dynamics.

To help us better understand what truly shaped this era, I will discuss it from three interconnected viewpoints.

1. The Court Environment and the Fall of Dong Zhuo

Let us begin with the political atmosphere inside the capital before Dong Zhuo entered.

Although the eunuchs appeared to wield enormous power, in reality they had neither armies nor real influence—only proximity to the emperor. Their situation was much like the Chinese idiom “a fox pretending to be a tiger,” creating an illusion of strength.

Dong Zhuo, however, was fundamentally different. He commanded more than two hundred thousand soldiers. Even when he marched toward the capital, he brought with him only ten to twenty thousand troops—yet this was already more than enough to overshadow the eunuchs entirely.

For nearly two centuries, the scholar-officials had resisted the idea of letting military strongmen interfere with imperial authority. But from Dong Zhuo’s standpoint, loyalty to a warlord felt more tangible than loyalty to the emperor. This mindset eventually drove him to attempt not only to dominate the court but to replace the emperor altogether.

Naturally, the ministers could not accept such ambition. They bribed Lü Bu—Dong Zhuo’s own adopted son—to assassinate him. Although Dong Zhuo was eliminated, the capital fell into chaos, countless factions emerged, and trust within the political center completely collapsed.

2. The Emperor’s Mindset and His Wandering Journey

Next, let us consider the psychological condition of the emperor and the imperial family.

Forced to flee in the midst of political turmoil, they wandered from one regional governor to another, hoping someone would shelter them. For generations, imperial family members had lived in comfort and were accustomed to being served. Suddenly deprived of security, they had no knowledge of how to survive on their own.

As a result, they lived in constant fear—unsure whom to trust, unsure even where they could safely rest. Eventually, one official accompanying the emperor suggested seeking refuge with Cao Cao.

Why Cao Cao?

Because his foster father, Cao Teng, had been the last respected eunuch of the Eastern Han—kind, restrained, and widely trusted. This connection offered a psychological anchor. The emperor believed Cao Cao might feel a sense of responsibility or sympathy toward the imperial family.

At that time, Cao Cao was already a complex figure—part statesman, part military strategist, and certainly a rising political force. Yet he was also someone who retained personal emotions and a sense of duty. Having grown up near the capital and visited the palace with his grandfather, he felt a familiarity with the royal household. His father had risen to high office thanks to Cao Teng, giving him yet another reason to protect the dynasty.

Because of all these emotional and psychological factors, Cao Cao made his crucial decision:

to escort the emperor to his base at Xuchang, safeguard him, and restore the legitimacy of the Han court.

Only many years later was the capital finally moved back to Luoyang.

3. The Mindsets of the Warlords

Lastly, let us examine the warlords themselves.

Those who had already built power through their own efforts were reluctant to bow to the emperor again. To them, submitting to imperial authority meant lowering themselves. Many preferred autonomy rather than surrendering the right to make their own final decisions.

However, simply holding the emperor without using his legitimacy was also pointless. Cao Cao’s advisers understood something crucial:

whoever controlled the emperor would hold the moral and political high ground when dealing with other warlords.

Many warlords hesitated between principle, pride, and self-interest.

But Cao Cao—guided by both emotional understanding and political calculation—acted decisively. His mindset allowed him to seize an opportunity others were too hesitant to grasp. And that single decision reshaped the direction of Chinese history.

Conclusion

What I hope to highlight is this:

Behind every historical event, beyond the battles and written records, lie deep psychological forces—personal fears, ambitions, loyalties, and beliefs that shape human behavior.

By understanding the mindsets of historical figures, we can also reflect on our own.

Before making any important decision—especially in the workplace—it helps to pause and consider not only our own psychological state, but also that of the people we interact with. When we understand these underlying factors, we make wiser, more grounded choices.

Thank you for listening.

#Power dynamics psychology#Decision-making under uncertainty#Learned helplessness#Machiavellianism leadership psychology#Psychological manipulation authority#Gratitude motivation behavior

Join as a free member to stay updated with the latest information: https://open.firstory.me/join/ckeiik73n1k6i08391xamn9ho

Make a small donation to support this program: https://open.firstory.me/user/ckeiik73n1k6i08391xamn9ho

Leave a comment to tell me your thoughts on this episode: https://open.firstory.me/user/ckeiik73n1k6i08391xamn9ho/comments

Powered by Firstory Hosting