The Emotionally Most Complete Cosmology

Description

One of my favorite restaurants is Buca di Beppo. The whole thing between the food and the decor is just a rich, overwhelming sensory overload. The portions are huge. The smallest plates feed at least two people. And the decor is an excessive splash of vibrant color and kitsch. The images are a jumbled mix of saints and sinners: nuns playing soccer, busty women sporting cleavage, iconography of the saints, ostentatiously nude statuary, and a giant bust of His Holiness the Pope. The bathroom might be the highlight of the whole experience. I haven’t seen the women’s room but the men’s room is a burlesque artistic celebration of the most undignified bodily functions. Yet the whole thing is somehow just barely “family friendly”. An American with less of a balmy Mediterranean and more of a conservative Puritan cultural background leaves the place wondering, “What just happened?”

I thought of Buca di Beppo when I first read an article by Alessandra Bocchi titled Cultural Christianity, Italian Mentality. What is it about Italian Catholic culture that makes it possible for Christian piety to coexist such uninhibited sensory indulgence? One possible response is that some indulgences that we think of as peccadillos aren’t really in conflict with piety and righteousness anyway. Wine and dance are not in themselves sinful. But Bocchi brings up another point that I find interesting, which is a certain understanding of human sinfulness and the function of forgiveness. An American said to Bocchi, about Italians, “so you just live in sin, and repent.” Bocchi says to this: “I couldn’t think of a better description. Individual, moral failures don’t negate the need for a moral structure of repentance and renewal — on the contrary, the evidence of the sin is proof for the necessity of upholding the Christian culture.”

A collection of the sayings of the Desert Fathers shares the following story: “A hunter in the desert saw Abba Anthony enjoying himself with the brethren and he was shocked. Wanting to show him that it was necessary sometimes to meet the needs of the brethren, the old man said to him, ‘Put an arrow in your bow and shoot it.’ So he did. The old man then said, ‘Shoot another,’ and he did so. Then the old man said, ‘Shoot yet again,’ and the hunter replied ‘If I bend my bow so much I will break it.’ Then the old man said to him, ‘It is the same with the work of God. If we stretch the brethren beyond measure they will soon break. Sometimes it is necessary to come down to meet their needs.’ When he heard these words the hunter was pierced by compunction and, greatly edified by the old man, he went away. As for the brethren, they went home strengthened.”

I’m simultaneously inspired both by the Biblical call to perfection – “Be ye therefore perfect” (Matthew 5:48 , KJV) – and with the Biblical recognition that human beings are not – “the spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak.” (Matthew 26:41 , KJV).

Not only that. We’re also supposed to enjoy and appreciate the world: Deuteronomy 8:7-10. JPS:

“For the Lord your God is bringing you into a good land, a land with streams and springs and fountains issuing from plain and hill; a land of wheat and barley, of vines, figs, and pomegranates, a land of olive trees and honey; a land where you may eat food without stint, where you will lack nothing; a land whose rocks are iron and from whose hills you can mine copper. When you have eaten your fill, give thanks to the Lord your God for the good land which He has given you.”

Deuteronomy 12:7, JPS: “Together with your households, you shall feast there before the Lord your God, happy in all your undertakings in which the Lord your God has blessed you.”

In the Jerusalem Talmud Kiddushin 4:12 it says that “In the future, a person will have to give an accounting before heaven for every good thing his eyes saw, but of which he did not eat.” Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch made sure that he took a trip to Switzerland before he died and explained: “When I stand shortly before the Almighty, I will be held accountable to many questions… But what will I say when… and I’m sure to be asked, ‘Shimshon, did you see My Alps?”

“To every thing there is a season” (Ecclesiastes 3:1, KJV). We eat food, but we don’t eat all the time. Sometimes we eat a lot of food, but we shouldn’t eat a lot of food all the time. We can drink wine, but we shouldn’t drink wine all the time. We can indulge our sexual appetites, but we don’t do it all the time, nor should we indulge all of them. Anyway it’s really the cyclic, non-constant nature of these things that make them enjoyable. We abstain for long enough to build up our desires so that it will be all the more enjoyable when they are satisfied.

C.S. Lewis related this to our nature as beings who exist in time, experiencing reality successively. In The Screwtape Letters, speaking in the mouth of a demon he said: “The humans live in time, and experience reality successively. To experience much of it, therefore, they must experience many different things; in other words, they must experience change. And since they need change, [God] (being a hedonist at heart) has made change pleasurable to them, just as He has made eating pleasurable. But since He does not wish them to make change, any more than eating, an end in itself, He has balanced the love of change in them by a love of permanence. He has contrived to gratify both tastes together in the very world He has made, by that union of change and permanence which we call Rhythm. He gives them the seasons, each season different yet every year the same, so that spring is always felt as a novelty yet always as the recurrence of an immemorial theme. He gives them in His Church a spiritual year; they change from a fast to a feast, but it is the same feast as before.”

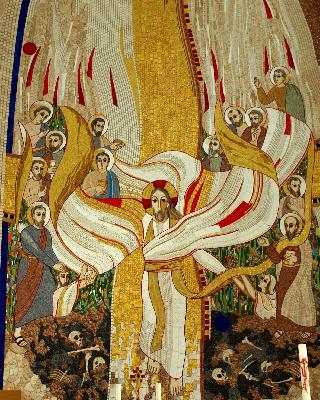

This is something I appreciate about Mardis Gras and Ash Wednesday. There is a time for Lenten asceticism. But there is also a time for feasting. I also think that there’s something to be said for both a minimalist aesthetic and for an aesthetic of sensory excess. There’s the great commandment to love the Lord your God with all your strength, בְכָל־מְאֹדֶֽךָ (be-kol meod-eka), with all of your “muchness” (Deuteronomy 6:5). Alessandra Bocchi’s writing about Italian culture reminds me of another Italian, Camille Paglia. Paglia has often spoken about her persisting appreciation of Italian Catholicism’s aesthetics of “florid pictorialism”, which she attributes to a certain retention of paganism. I don’t know about that, at least theologically, but aesthetically that might be right. She fondly recollects from her upbringing: “I loved the cult of saints, the bejeweled ceremonialism, the eerie litanies of Mary… My baptismal church, St. Anthony of Padua in Endicott, New York, was a dazzling yellow-brick, Italian-style building with gorgeous stained-glass windows and life-size polychrome statues, which were the first works of art I ever saw.”

Paglia explores her interpretation of Italian Catholicism in her book, Sexual Personae:

“Paganism is eye-intense. It is based on cultic exhibitionism, in which sex and sadomasochism are joined. The ancient chthonian mysteries have never disappeared from the Italian church. Waxed saints’ corpses under glass. Tattered armbones in gold reliquaries. Half-nude St. Sebastian pierced by arrows. St. Lucy holding her eyeballs out on a platter. Blood, torture, ecstasy, and tears. Its lurid sensationalism makes Italian Catholicism the emotionally most complete cosmology in religious history. Italy added pagan sex and violence to the ascetic Palestinian creed.”

You get a sense there of Paglia’s over-the-top, shock-value style, which I wouldn’t take fully at face value. And this might not be the aspect of Catholicism that Catholics would want to highlight. But, I think it’s an interesting compliment and can be taken as such. It reminds me again of a feast day at Bucca di Beppo.

Here’s another passage from Sexual Personae that includes some personal recollections:

“To this day, relatives in my mother’s village near Rome visit the cemetery every Sunday to lay flowers on the graves. It is a kind of picnic. I remember childhood feelings of chill and awe at the candle kept burning by my grandmother before a photograph of her dead daughter Lenora, the small, round yellow flame flickering in the darkened room. A sense of the mystic and uncanny has pervaded Italian culture for thousands of years, a pagan hieraticism flowering again in Catholicism, with its polychrome statues of martyred saints, its holy elbows and jawbones sealed in altar stones, and its mummified corpses on illuminated display. In a chapel in Naples, I recently counted 112 gold and glass caskets of musty saints’ bones stacked as a transparent wall from floor to ceiling. In another church, I found a painting of the public disembowelling of a patient saint, his intestines being methodically wound up on a large machine like a pasta roller. Nailed like schools of fish to church walls are hundreds of tiny silver ears, noses, hearts, breasts, legs, feet, and other body parts, votive offerings by parishioners seeking a cure. Old-style Italian Catholicism, now shunned by middle-class WASP-aspiring descendants of immigrants, was full of the chthonian poetry of paganism. The Italian imagination is darkly archaic. It hears the voices of the dead and identifies the passions and torments of the body with