The Major Histocompatibility Complex and Antigen Presentation (Immunology Part 7)

Description

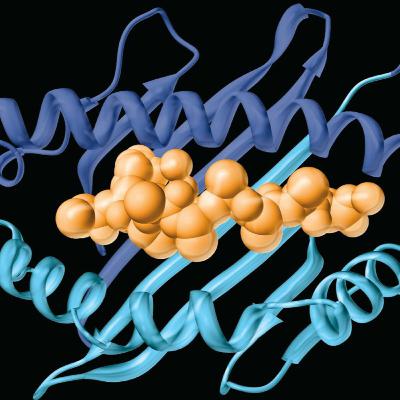

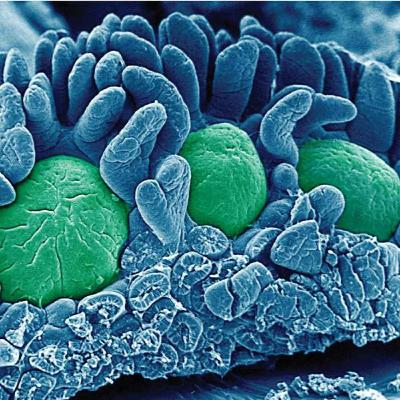

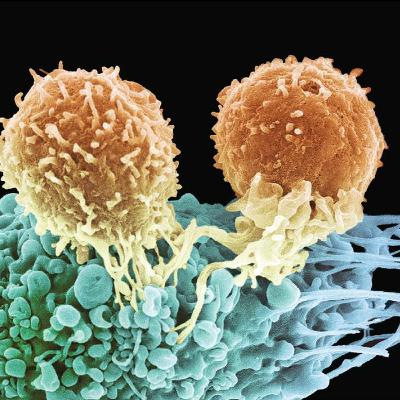

If antigen-presenting cells serve as the bridge between innate and adaptive immunity, then MHC molecules act as the essential tools enabling this connection. These molecules hold antigenic fragments and present them to T-cell receptors, activating the corresponding T cell and initiating the adaptive immune response. As transmembrane proteins, MHC molecules are expressed on the surface of cells and are widely distributed throughout the body. They exhibit significant diversity at both individual and population levels due to evolutionary pressures from pathogens, which have driven gene duplication, polymorphism, and codominant expression patterns. For antigens to associate with MHC molecules, they must first be processed into smaller fragments and transported to cellular locations where they can bind and stabilize the MHC structure before being presented on the cell surface. The shape and chemical properties of the MHC antigen-binding groove, determined by the inherited alleles at this locus, dictate the types of antigenic fragments that can be presented to T cells. This, in turn, determines which portions of infectious agents are recognized and which naïve T cells are activated. Since most B cells, which do not require MHC involvement for antigen recognition, depend on T-cell assistance for full activation, MHC-mediated antigen presentation becomes central to the adaptive immune response. Consequently, diversity in the MHC gene locus benefits individual hosts and enhances species survival by maintaining a diverse MHC gene pool within the population.