To Lock Death in a Dark Room

Update: 2025-09-30

Description

By Thomas Harrington at Brownstone dot org.

[The following is an excerpt from Thomas Harrington's book, The Treason of the Experts: Covid and the Credentialed Class.]

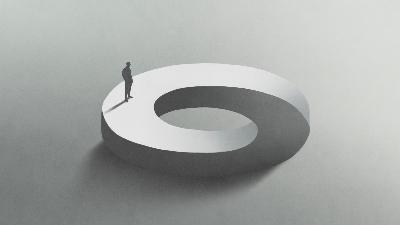

Most of us, I suspect, have had the experience of walking into a darkened room we presume to be empty, only to find someone sitting silently in the shadows observing our movements. When this happens, it is, initially at least, an unnerving experience. Why? Because, though we don't often speak about this, there are things we do, think about, and say to ourselves when alone that we would never allow ourselves to do, think about, or say to ourselves in the presence of others.

When seeking to understand what Bourdieu called the "structuring structures" of a culture it helps to have a keen ear for language, and more specifically still, an ability to register the ways in which certain terms have entered or left the culture's everyday lexicon over the course of our lives.

For example, while terms like "fuck" and "suck," which were once reserved for the expression of our most savage emotions have gone banally mainstream, words like dignity and integrity, which embody timeless and universal ideals have become surprisingly scarce.

On those few occasions when it is uttered today, integrity is pretty much used as a synonym for honesty. While this is not wrong, I think it gives short shrift to the fullness of the concept lurking behind the word. Viewed etymologically, to have integrity is to be integral, that is, to be "one of a piece" and therefore largely devoid of internal fissures.

In practice, this would mean being - or more realistically - assiduously seeking, to become the same person inside and out, to do what we think, and think about what we do.

Going back to the example of the dark room above, having true integrity would mean getting to a point where the sudden presence of the other person in the shadows would not disturb us because he or she would be seeing nothing in us that we would not want to be seen, or that we had not displayed openly on countless occasions in public settings.

There is, I believe, also an important existential correlate to this idea of integrity. It might be summed up as the ability to enter into an active, honest, and fruitful dialogue with what awaits us all: diminishment and death.

It is only through a constant and courageous engagement of the mystery of our own finiteness that we can calibrate the preciousness of time, and the fact that love and friendship may, in fact, be the only things capable of mitigating the angst induced by its relentless onward march.

There is nothing terribly new in what I have just said. Indeed, it has been a core, if not the core, concern of most religious traditions throughout the ages.

What is relatively new, however, is the full-bore effort by our economic elites and their attendant myth-makers in the press to banish these issues of mortality, and the moral postures they tend to channel us toward, from consistent public view. Why has this been done?

Because talk of transcendent concerns like these strike at the core conceit of the consumer culture that makes them fabulously wealthy: that life is, and should be, a process of endless upward expansion, and that staying on this gravity-defying trajectory is mostly a matter of making wise choices from among the marvelous products that mankind, in all its endless ingenuity, has produced, and will continue to produce, for the foreseeable future.

That the overwhelming majority of the world does not, and cannot, participate in this fantasy, and continues to dwell within the precincts of palpable mortality and the spiritual beliefs needed to palliate its day-to-day angst, never seems to occur to these myth-makers.

At times, it is true, the muffled screams of these "other" people manage to insinuate themselves into the peripheral reaches of our public conversation. But no sooner do they appear than they are summarily banished under a concerted rain of imprecation, ...

[The following is an excerpt from Thomas Harrington's book, The Treason of the Experts: Covid and the Credentialed Class.]

Most of us, I suspect, have had the experience of walking into a darkened room we presume to be empty, only to find someone sitting silently in the shadows observing our movements. When this happens, it is, initially at least, an unnerving experience. Why? Because, though we don't often speak about this, there are things we do, think about, and say to ourselves when alone that we would never allow ourselves to do, think about, or say to ourselves in the presence of others.

When seeking to understand what Bourdieu called the "structuring structures" of a culture it helps to have a keen ear for language, and more specifically still, an ability to register the ways in which certain terms have entered or left the culture's everyday lexicon over the course of our lives.

For example, while terms like "fuck" and "suck," which were once reserved for the expression of our most savage emotions have gone banally mainstream, words like dignity and integrity, which embody timeless and universal ideals have become surprisingly scarce.

On those few occasions when it is uttered today, integrity is pretty much used as a synonym for honesty. While this is not wrong, I think it gives short shrift to the fullness of the concept lurking behind the word. Viewed etymologically, to have integrity is to be integral, that is, to be "one of a piece" and therefore largely devoid of internal fissures.

In practice, this would mean being - or more realistically - assiduously seeking, to become the same person inside and out, to do what we think, and think about what we do.

Going back to the example of the dark room above, having true integrity would mean getting to a point where the sudden presence of the other person in the shadows would not disturb us because he or she would be seeing nothing in us that we would not want to be seen, or that we had not displayed openly on countless occasions in public settings.

There is, I believe, also an important existential correlate to this idea of integrity. It might be summed up as the ability to enter into an active, honest, and fruitful dialogue with what awaits us all: diminishment and death.

It is only through a constant and courageous engagement of the mystery of our own finiteness that we can calibrate the preciousness of time, and the fact that love and friendship may, in fact, be the only things capable of mitigating the angst induced by its relentless onward march.

There is nothing terribly new in what I have just said. Indeed, it has been a core, if not the core, concern of most religious traditions throughout the ages.

What is relatively new, however, is the full-bore effort by our economic elites and their attendant myth-makers in the press to banish these issues of mortality, and the moral postures they tend to channel us toward, from consistent public view. Why has this been done?

Because talk of transcendent concerns like these strike at the core conceit of the consumer culture that makes them fabulously wealthy: that life is, and should be, a process of endless upward expansion, and that staying on this gravity-defying trajectory is mostly a matter of making wise choices from among the marvelous products that mankind, in all its endless ingenuity, has produced, and will continue to produce, for the foreseeable future.

That the overwhelming majority of the world does not, and cannot, participate in this fantasy, and continues to dwell within the precincts of palpable mortality and the spiritual beliefs needed to palliate its day-to-day angst, never seems to occur to these myth-makers.

At times, it is true, the muffled screams of these "other" people manage to insinuate themselves into the peripheral reaches of our public conversation. But no sooner do they appear than they are summarily banished under a concerted rain of imprecation, ...

Comments

In Channel