Why I Talk About Agorism

Description

by James Corbett

corbettreport.com

October 26, 2025

The always provocative (and thought-provoking) Larken Rose recently posted a video, “Why I Don’t Talk About Agorism.” If you haven’t seen it yet, you should:

(And, after you watch it, you should subscribe to his channel and buy his book.)

Long story short, Larken makes the point that he doesn’t talk about “the philosophy of agorism” because agorism is not a philosophy. It’s a tactic. The philosophy underlying the agorist tactic is voluntaryism. Ergo, he talks about voluntaryism, not agorism.

I understand his point, but I suppose I’ll make the argument for agorism as a philosophy.

So, are you the type of person whose eyes glaze over when people start talking about philosophy? Do you want to gouge your eyes out with a rusty spoon at the mere mention of political ideology? Then you can go on with your day. You will not enjoy this editorial.

Conversely, are you interested in political philosophy? Would you like to know more about agorism, voluntaryism, and the praxis of anarchy? Then this is the editorial for you. Read on!

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

WHAT IS AGORISM?

First, let’s start out as every fruitful discussion on complex topics should: by defining our terms.

Voluntaryism is perhaps most succinctly defined at voluntaryist.com:

Voluntaryism is the doctrine that relations among people should be by mutual consent, or not at all. It represents a means, an end, and an insight. Voluntaryism does not argue for the specific form that voluntary arrangements will take; only that force be abandoned so that individuals in society may flourish. As it is the means which determine the end, the goal of an all voluntary society must be sought voluntarily.

Even in this simple definition, however, you start to see the tensions between philosophy as ideology and philosophy as practice that Larken points to in his own commentary. In this formulation, for instance, voluntaryism is both a means and an end (and, as an added bonus, it’s also an insight!).

But if voluntaryism is indeed a means, than what are those means? Surely, the “means” of a voluntary society is the practice of engaging in voluntary relations with others and eschewing coercion and offensive force. This is where agorism comes in.

The next logical question, of course, is: what is agorism?

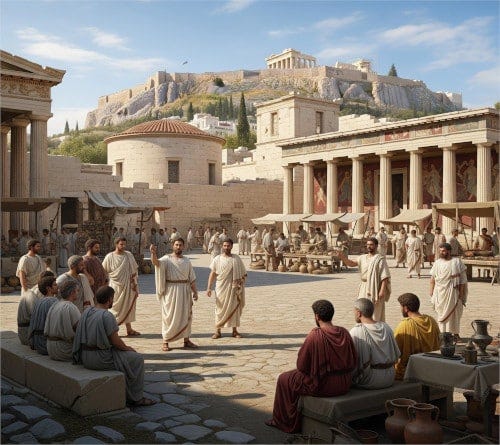

The name itself derives from “agora” (ἀγορά in Greek), which is generally translated as “marketplace.” But the ancient Greek agora was not merely a marketplace in the crass sense of our modern understanding of that word. It was a public square, a gathering place where people could exchange not only goods but also ideas. A place where they could cooperate, argue and καταλλάσσω (katallassó), i.e., not just exchange goods or ideas but engage in the reconciliation that forms the basis of human society.

There is much more to be said about these topics and the associated study of catallactics, but using “a space for the voluntary, mutually beneficial interactions of free people to play out” as a rough definition of the agora, we can now turn to famed voluntaryist philosopher Samuel E. Konkin for a definition of agorism.

Konkin opens his seminal work on the subject, The Agorist Primer, with the simplest explanation of the word “agorism” you will ever read: “Agorism can be defined simply: it is thought and action consistent with freedom.”

But, like all succinct definitions for complex words, Konkin acknowledges that this description, too, leaves much room for interpretation: “The moment one deals with ‘thinking,’ ‘acting,’ ‘consistency,’ and especially ‘freedom,’ things get more and more complex.”

Indeed.

So, how about this definition from later on in the same chapter: “Agorism is the consistent integration of libertarian theory with counter-economic practice; an agorist is one who acts consistently for freedom and in freedom.”

The only problem here is that we encounter yet another new term: counter-economics. Those who have read my editorial on “You’re Already a Criminal: An introduction to counter-economics“ will know that Konkin defines counter-economics thusly:

All (non-coercive) human action committed in defiance of the State constitutes the Counter-Economy.

As I go on to elaborate in my editorial, everything from driving over the speed limit to paying a contractor in cash under the table to cutting someone’s hair without a license could fall under the category of “counter-economic activity”—provided that action is “committed in defiance of the State.” It is by reducing the scope of the state’s power over citizens—and thereby, often depriving the state of its tax revenue—that the counter-economist helps to create a freer world.

There is obviously much more to learn and to understand about the counter-economy, about the consistent application of libertarian principles, and about “acting consistently for freedom and in freedom,” but at least we n