Wired into Pain

Description

This is a repost from 2018, an article caled Wired Into Pain: a history of the science of pain. I hope you enjoy it. I’ve also recorded an audio version to go with it!

[2024 AUTHOR’S NOTE: I think this piece (from 2018) is still a hugely valuable introduction to the history of pain science, rich in detail. But there are some mis-steps towards the end, where it veers into a bit of a triumphalist view of recent pain science. I can’t spot much that is flat-out wrong, but I wish there were other perspectives. Don’t let that put you off reading].

I am a Physiotherapist. Almost every person I see in clinic is in pain, and most already have an idea about what has caused their pain. If they are old enough, they might say ‘overuse’, or ‘wear and tear’; if they are younger, they might say ‘bad posture’ or ‘tight muscles’; if they have had a scan, they might say a ‘slipped disc’ or a ‘bone spur’. We accept these explanations prima facie. We consider pain to be a readout on the state of the body’s tissues. Or, as one doctor wrote in 1917, it is “the unerring medical compass that serves as a guide to the pathological lesion”.

But it is only very recently that we have come to understand our aches and pains in this way. Since medieval times, until surprisingly recently, people commonly understood their pains in terms of their relationship to God, often as punishment for sin. Physical and emotional pain were entangled, along with mind, body and soul. This was the grim logic of medieval torture and self-flagellation: the truth of the soul could be accessed through the pain of the body.

But, as historian Joanna Bourke records in her book The Story of Pain, this mixture of mind, body, soul and God also allowed people to feel pain as comforting: a “vigilant sentinel […] stationed in the frail body by Providence”, as one writer put it in 1832. For others, pain was redemptive: take, for example, the early nineteenth-century labourer Joseph Townend, who resolved himself to God after undergoing surgery without anaesthetic, and reflected at the end of his life on his “sincere thanks to the Almighty God” for his agonising conversion.

Pre-modern physicians had a different perspective. Most understood pain according to humoural theory. Hippocrates and his disciple Galen considered all illness to be caused by an imbalance of the body’s humours — phlegm, yellow bile, black bile and blood — which ebb and flow in response changes in the body or its environment. This notion endured for many centuries. To one 18th century writer, pain was a consequence of “viscid blood [stopping] at every narrow passage in its progress”; to another, it was a “Nature throw[ing] a Mischief” about his body. Humoural theory is pre-scientific and seems quaint to us now. But, as Bourke points out, it accounts for an abundance of influences, from our personal temperament and our relationships to the alignment of the planets above our heads, on the pain that we feel.

Over the coming centuries, at great cost to people suffering from pain, this insight was lost. This is the story of that loss; of how we arrived at the strange, wrong idea that pain is a straightforward “guide to the pathological lesion”; and of how an emerging re-understanding of pain shows us that it is more complex and more astonishing than we have thought for centuries.

Descartes, dualism and the labelled line

“The ghost in the machine” — Gilbert Ryle

It is in the sixteenth century that we find the beginnings of the dominant modern understanding of the body and its pains. The rise of Protestantism and, amongst secular thinkers, of humanism, contributed to an increased focus on the individual and an understanding of the body as a natural, rather than a supernatural entity. Medicine became more interested in anatomy and the physical laws of nature. Vesalius published his On the Fabric of the Human Body, a compendium of illustrations of dissected cadavers based on the author’s strict, first-hand observations at a time when doctors were not accustomed to performing their own dissections. Later, physicians like William Harvey took principles from physics and astronomy to show that in many ways, our bodies can be understood as machines: pumps, pulleys and levers. Slowly, the body became less sacred and more scientific.

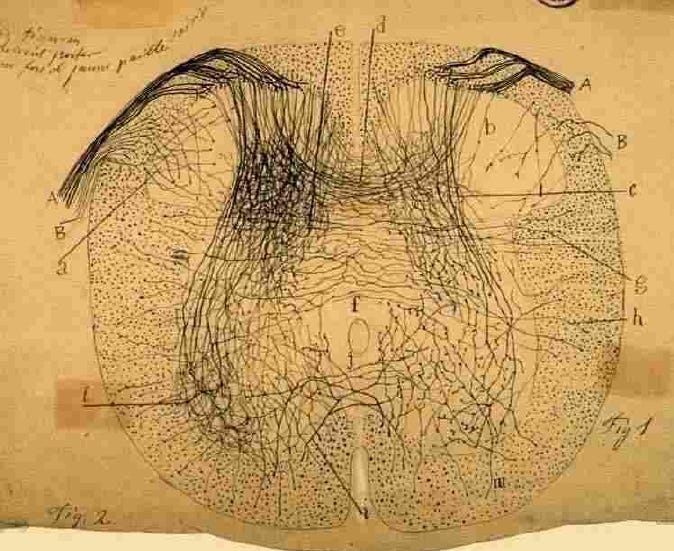

It was in this spirit that, in 1641, the French polymath Renes Descartes published his Meditations on First Philosophy. This work contains a drawing that became the seminal image of pain for the next three hundred years. The picture shows a kneeling boy with one foot perilously close to a small campfire. The heat of the flame sends a signal (an “animal spirit”) up a channel to the boy’s pituitary gland, which Descartes reckoned was the seat of consciousness. There, the signal elicits pain, “just as pulling one end of a cord rings the bell at the other end”.

This picture makes sense to us, it seems intuitively correct. But this is because in matters of pain we are most of us now, in the Western world at least, the children of Descartes. For pain scientists on the other hand, who have fought in recent decades to emancipate themselves from Descartes, this picture has has come to represent the original sin, the first big lie of the Western world’s understanding of pain.

It’s crimes are twofold. First, it is the essence of an idea called dualism, which holds that mind and body are separate. The body feels pain, and passes this information on to the mind. For Cartesian dualists, the body is a machine and we are a kind of ghost in the machine, receiving information about its status.

Second, the picture represents pain as being felt by a specific detector in the body, and passed up a specific pathway, the long hollow tube, to a specific location in the boy’s brain. Pain detectors, at the end of a pain pathway, that leads to a pain centre. This idea is called specificity theory, but in this post I’m going to use the term labelled line theory because although it is less common, I think it is more descriptive — a labelled line for pain.

As it happens, Descartes’ idea was more subtle than the picture and its subsequent interpretations made out. In his defence, the historians Jan Frans van Dijkhuizen and Karl A.E. Enenkel point out that Descartes knew that pain is not merely perceived, like a mariner perceives his ship, but felt, as if the mind and body are “nighly conjoin’d […] so that I and it make up one thing”. Descartes knew that we don’t just have a body; we are a body. But this subtlety was lost: the picture of the little boy with his foot in the fire has a memetic power that has carried it, along with dualism and the labelled line, through the centuries.

The nineteenth century

“Nothing less than the social transformation of Western medicine” — Daniel Goldberg

This change came gradually. It was not until the nineteenth century, two hundred years after Descartes’ Meditations, that dualism and the labelled line for pain finally established their authority in medicine.

They set in as part of a wider change in the history of medicine following the French Revolution that is sometimes now called the ‘Paris School’. The physicians of the Paris School transformed large teaching hospitals in the city to dedicate them, for the first time, to furthering scientific knowledge through rigorous observation of patients and cadavers, and the classification of disease. They explicitly rejected humoural theory, which held that illnesses are processes that are distributed around the body through the movement of viscous humours. Rather, physicians of the Paris School considered diseases to be the result of lesions localised to a single, solid organ.

Influenced by the Paris School, Victorian physicians across the Western world began to search their suffering patients’ bodies for a local, solid lesion to blame for their pain. As one New York physician wrote in 1880, “we fully agree that there can be no morbid manifestations without a change in the material structure of the organs involved”. For the first time, doctors began to think like detectives on the hunt for the smoking gun, following clues provided by the body and its sensations (it is no coincidence that Arthur Conan Doyle was a doctor before he wrote the Sherlock Holmes stories, or that he made his character Watson one, too).

This approach has tremendous diagnostic power. But, as we will see, even modern researchers find that our pain, particularly our chronic pain, resists reduction by detective work. How did Victorian physicians respond when their investigations failed to turn up a local lesion to explain pain? According to historian and medical ethicist Daniel Goldberg, many doubled down, hunting for anything they could find. As one surgeon put it, “any lesion anywhere in the body will do to account for an otherwise inexplicable pain”. And that meant any lesion: the surgeon Joseph Swann, or example, baffled by a woman’s 11-year history of pain in an apparently healthy knee, eventually attributed it to an imperfection he found, after much searching, in a nerve in her hand.

Those that could not find a lesion anywhere explained unexplained pain as one inevitably must if one subscribes to the logic of dualism: if it’s not in the body, it must be in the mind. Goldberg tells the story of the surgeon Josiah Nott who, in 1872, took on the care of an American soldier whose leg was crushed in a railway accident. The leg had already been amputated by another surgeon at a point about halfway up the calf, but the soldier had developed phantom limb

![The mechanisms of radicular pain, with Annina Schmid [Repost!] The mechanisms of radicular pain, with Annina Schmid [Repost!]](https://substackcdn.com/feed/podcast/30808/post/120725418/648a121404e9ec2f43a3efe90cc51640.jpg)