‘We are fully sustainable’ - The rise of Catholic microschools

Description

At the beginning of the school year in autumn 2022, St. Athanasius had $8,000 in the bank, a $4,000 bill, around 80 students enrolled, and a brand new principal.

The small Catholic school in Long Beach, California was on the verge of shutting down — and it was Sonia Nuñez’s job to save it.

She took out a $5,000 payroll loan, hired new staff members and announced that the school would be switching to a microschool model — grouping multi-age students in the same classroom.

Under the new model, the number of classes was reduced from 10 to five, staffing was cut in half, and Nuñez focused on learning the names of all 82 students.

—

Four years later, enrollment has increased by 20 students, test scores have improved dramatically, parents are more engaged and the school ended last year with $100,000 in the bank.

“Microschooling was a last-ditch effort to save the school financially,” Nuñez told The Pillar. “Now, we are fully sustainable. We have gone basically from so deep in the red we almost had to close our doors, to the black now.”

“Our students were not receiving curriculum at their grade level but when we started teaching in the multi-grade classroom approach, we saw test scores starting to go up,” Nuñez added. “We have also noticed that the current second graders who are the students that have had nothing but microschooling are the highest performing students in the school.”

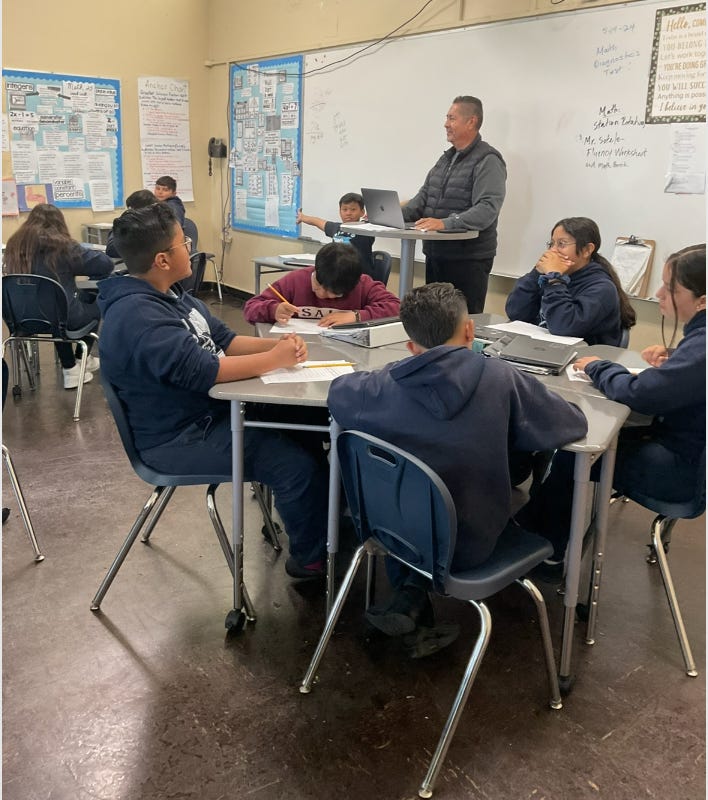

Microschooling is an approach for institutions with fewer than 150 students; it involves teaching students in multi-age classrooms, where teachers focus on teaching to individual students, rather than the class. The National Microschooling Center reports that there were 800 registered microschools as of May 2025.

The center reports that 50% of microschools are private centers serving homeschooled students, 30% are private institutions — including Catholic schools, 5% are charter schools, and the other 11% split among other structures.

The center notes that a microschool’s defining elements ”are innovative small learning environments, which have generally been established outside of traditional public education systems.”

The data

St. Athanasius is one of five microschools in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and one of the 22 Catholic microschools in the United States that has registered with the National Catholic Educational Association.

There are others, even if they’re harder to count — independent classical institutions like Chesterton Academies, or homeschooling co-ops.

The pandemic altered the landscape of Catholic education as both homeschooling and Catholic liberal education grew in popularity. Since the pandemic, microschooling has become a growing trend across the United States in both Catholic and secular circles as more small schools faced the prospect of shutting down.

There are 5,852 Catholic schools in the country, 30% of which have 150 students or fewer.

In the 1960s more than 5 million students attended Catholic schools — a high point for Catholic education. But since then, enrollment has dropped. Ten years ago there were 1,939,574 students enrolled in Catholic schools according to the National Catholic Educational Association. Today, there are 1,683,506 students.

A decline of more than 250,000 students in one decade is no small thing.

And according to data released by the NCEA, that declining enrollment meant that in recent years, about 100 U.S. Catholic schools have closed annually — and in 2021, 209 schools closed across the country, the most in any year.

During the pandemic, as hundreds of Catholic schools faced closure, Dr. Jill Wierzbicki, a former vice president at NCEA, and Dr. Kevin Baxter, former superintendent at the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and former NCEA chief innovation officer, aimed to address the issue.

The two researched microschools for their book: “Greatness in Smallness: A Vision for Catholic Microschools.”

“The traditional mindset is that if a school has [low] enrollment you ask, where do I find more kids?” Baxter told The Pillar. “Sometimes, that’s a really good approach. But in our world today, kids might just not be there, or there might be factors at play preventing a boost in enrollment.”

“Thus we started thinking about this more intentionally, asking if there was a way we could start to plan more thoughtfully about how to help schools sustain themselves, if their enrollment was not going to be sufficient [to support a traditional school model].”

Microschools seemed to be the answer — at least as Wierzbicki and Baxter saw it.

“It is almost like we put the cork in the sinking ship,” Wierzbicki told The Pillar. “We found a way to greatly decrease the number of closures. Once we published the book, suddenly people were talking about their smaller schools differently. They saw an option that wasn’t an immediate closure.”

After the pandemic, Catholic school closures have decreased with 71 closing in 2021-2022, 37 between 2022-2023, 55 between 2023-2024 and 63 between 2024-2025.

“We were closing a few hundred schools in 2019, 2020, 2021,” Wierzbicki said. “Then it got down to like two digit numbers, as soon as we started talking about microschooling.”

As dioceses continue to address declining enrolments, Baxter believes they should consider microschools, before presuming they’ll need to close or merge schools.

“Each parish and school has its own identity, and they want to maintain that community, and they want to continue to serve the community that they’ve served for generations,” Baxter said. “