Discover Museum Archipelago

Museum Archipelago

Museum Archipelago

Author: Ian Elsner

Subscribed: 620Played: 3,145Subscribe

Share

© 2025 Ian Elsner

Description

A tiny show guiding you through the rocky landscape of museums. Museum Archipelago believes that no museum is an island and that museums are not neutral.

Taking a broad definition of museums, host Ian Elsner brings you to different museum spaces around the world, dives deep into institutional problems, and introduces you to the people working to fix them. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes, so let’s get started.

Taking a broad definition of museums, host Ian Elsner brings you to different museum spaces around the world, dives deep into institutional problems, and introduces you to the people working to fix them. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes, so let’s get started.

111 Episodes

Reverse

Museums today are filled with software, yet they've largely avoided being "eaten" by the tech industry. Unlike music or movies, exhibitions can't be downloaded or scaled infinitely. There's only one Mona Lisa. But if the wrong platform finds the right leverage, that immunity may not last.

Which is why the kind of software museums choose matters. TilBuci (https://tilbuci.itch.io/tilbuci) is a free, open-source tool used by museums to build touchscreens, kiosks, and projections. It was created by Brazilian software developer Lucas Junqueira after watching too many digital exhibitions quietly break down once the opening buzz faded. Designed to be usable by museum staff long after developers leave, TilBuci treats software not as a product, but as infrastructure.

In this episode, Lucas Junqueira talks about what it takes to build museum software that lasts. Through the story of a projection still running on the facade of the Space of Knowledge museum in Belo Horizonte over a decade after it opened, we explore how open, locally controlled tools extend the life of museum systems, and what's at stake if a tech platform ever inserts itself between museums and their audiences.

Image: A projection animates the façade of the Espaço do Conhecimento (Space of Knowledge) museum at Praça da Liberdade (Liberty Square) in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Lucas Junqueira's software Managana, a previous version of TilBuci is running the projection.

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 The Rise of Software in Museums

00:56 Software Eating the World

02:19 Why Are Museums Different?

03:16 Lucas Junqueira and TilBuci (https://tilbuci.itch.io/tilbuci)

05:09 Challenges and Innovations

08:09 The Flash Apocalypse

10:12 What's at Stake

11:48 Jurassic Park on Club Archipelago (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

13:00 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

DIVE DEEPER WITH CLUB ARCHIPELAGO 🏖️

Unlock exclusive museum insights and support independent museum media for just $2/month.

Join Club Archipelago

Start with a 7-day free trial. Cancel anytime.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

🎙️Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don't make it into the main show.

🎟️ Archipelago at the Movies, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies and other pop culture that reflect the museum world back to us.

✨A warm feeling knowing you're helping make this show possible.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 111. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsner. Museum Archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes. So let's get started.

If you've been to a museum lately, any museum big or small, you've probably noticed ever more software-driven experiences. Interactive touchscreens, projections, buttons, videos are all controlled by software.

Lucas Junqueira: I've seen mostly all exhibitions have at least some kind of interaction or some pieces of the exhibition that require some kind of software to enable it.

This is Lucas Junqueira, a Brazilian museum professional and software developer.

Lucas Junqueira: Okay. My name is Lucas Junqueira. I've been working on this exhibition museum scene for quite some time right now.

It's tempting to see the increase of software in museums as another example of software eating the world. This phrase, "software eats the world", was coined by investor Marc Andreessen in a 2011 Wall Street Journal opinion piece.

The idea isn’t that software replaces everything. It’s that software absorbs the value layer of company after company, industry after industry.

In the "software eats the world" thesis, traditional music labels only exist to provide software companies (like Apple Music and Spotify) with content. The software, everything from how the app looks on your phone to what song is recommended next, sits higher on the value chain than the music itself. Even the network effects of which app your friends use, matter more than what you listen to.

Netflix, Salesforce, and the game Angry Birds are some examples Andreessen mentioned back in that 2011 essay, plus plenty of other companies I barely remember. But the core of the thesis, even if it's not explicitly mentioned, is the zero-marginal cost nature of distributing software. Whatever the up-front cost of developing Angry Birds is, it doesn't actually matter since the company can distribute it to every phone on the planet for zero dollars. Once it exists, it can be copied endlessly, instantly, and globally. Which is exactly what museums can’t do.

And this is where museums are different.

Museums aren’t infinitely scalable, and they aren’t frictionless. You can't really download an exhibition in the way that you can download a song. You have to show up. There's only one Mona Lisa.

And that's why software in museums is (so far at least) immune from software eating the rest of the world.

Yes, there's more software in museums than ever, but that software rarely becomes the value layer.

Museum software doesn't own the audience relationship, and it doesn't become the product like Spotify was able to do. Instead, it supports the product. As long as museums continue to control distribution, software remains infrastructure: a tool to help museums tell their stories.

Lucas and I are both software developers, specializing in building exactly that infrastructure.

One of Lucas's early projects was creating software to project images onto the facade of the Space of Knowledge museum, which faces Liberty Square plaza in the Brazilian town of Belo Horizonte.

Lucas Junqueira: We provided them a tool so they can make, a projection. They do have a projection on the front wall of the museum. It's a very big projection, and it is right in front of a square here in my city that is very crowded all the time.

So they wanted to use this to show something they are exhibiting right now the museum is funded by a university, so they wanted to show some scientific evolutions. They want to use it like an information tool. They wanted to do that and provided them with the software used to produce the content to show on this big projection.

Almost always, the cost of these projects is front-loaded: museums pay Lucas, or me, to create the software that projects the images and everyone is focused on that opening day. Lucas explains that this focus on new exhibitions is related to sponsorship funding.

Lucas Junqueira: We see that,, most of the museums had some requirements when they start a new exhibition, they usually have some kind of budget and some kind of funding to that. And that doesn't really happen when these institutions have to maintain their spaces. They can get some sponsors to new exhibitions, but they don't get so many sponsors when they are just keeping the museum open, right?

And this is what happened to the projection on the facade of the Space of Knowledge museum. Long after Lucas finished building the software, and long after the project had successfully finished, the museum wanted to update that projection to show new content.

Lucas Junqueira: And it was these, that, brought me the idea of creating a tool so the people on museum can use it without technical knowledge, because I felt they were needing to create some interactive content, but they needed to do it by themselves.

Lucas wanted to make software that acted like infrastructure.

Lucas Junqueira: And I felt this need to create something that the museums and the, institutions can use to both create the big exhibitions, the big interactions for the new exhibitions, but also something that they can use, on by day, day basis.

Lucas Junqueira: Because they don't have that sort of technical people or budget to fund these on a day by day basis. Right? And so when I started thinking about creating something that they can used for both things. They can use it when something new is coming and they can hire people to do it. They can hire technical people, they can hire developers to do it, but something that they can install on their computers and with minimal knowledge they can use to solve day by day problems.

The result is TilBuci, a piece of software that Lucas developed on his own. It's a tool for helping build the software infrastructure a museum might need. The name TilBuci comes from Lucas's dog.

Lucas Junqueira: His name is Busi He, he keeps company for me. He is always where I am. When I'm working, he's close to me all the time. So when I had to think about that name first I thought, that would be perfect, let's name after him!

TilBuci, which you can download for free on any OS platform you want, is an impressive suite: capable of doing anything from slideshows, interactive menus with animation, dialogue systems, survey kiosks, and quiz games.

Lucas Junqueira: It started growing slowly with the functions that started growing slowly because of course it's a free software and it's not funded by anyone. Well, it's funded by my own work. Right? So, I started creating like this. So when someone hired me to develop, for example, a kiosk and I had to build a, a in specific function instead of creating it somewhere else, I use it on that case, I create, I use it to create the code and incorporate it on the base software.And so the, the, the basis of, of TilBuci started that. It started growing from the day by day work, my of myself.

But it wasn’t without setbacks. Lucas’s early code was written to be distributed on Flash. Flash Player was, for a long time, an easy way to make interactive media work on the web and in museums. It w

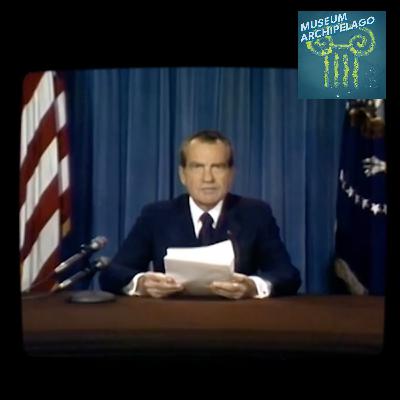

For the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum planned to display the Enola Gay, the Boeing B-29 that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The plane was restored to be part of a full exhibit, presented alongside context about the atomic bombing's mass civilian casualties.

But that exhibit never opened. Instead, after years of script revisions and intense pressure from veterans' groups and Congress, the museum displayed the restored bomber's fuselage with minimal interpretation. The exhibit was primarily dedicated to the technical process of restoring the aircraft; as one visitor noted, "I learned a lot about how to polish aluminum, but I did not learn very much about the decision to drop the atomic bomb."

In this episode, historian Gregg Herken, who served as Chairman of the museum's Space History Division during the controversy, recounts how the exhibit went from reckoning with the bomb's full impact to re-enforcing a patriotic narrative. He recalls the specific moments that led up to one of the museum industry's cautionary tales, like when the director agreed to remove evocative artifacts like a schoolgirl's carbonized lunchbox from Hiroshima from the exhibition plans, and how the Air Force Association demanded the exhibit say the bombing saved 1 million American lives and other assertions that have been challenged by generations of historians.

Today, as a new presidential executive order (https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/03/restoring-truth-and-sanity-to-american-history/) dictates how the Smithsonian interprets American history, we realize the "Enola Gay Fiasco" isn't just a cautionary tale—it's the blueprint for a more aggressive campaign to justify anything.

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 The Enola Gay in the 1980s

01:07 Gregg Herken

02:21 Initial Planning

02:40 Martin Harwit

03:48 Herken's Visit to Hiroshima

04:39 'The Lunchbox' (https://hpmmuseum.jp/modules/exhibition/index.php?action=DocumentView&document_id=362⟨=eng)

05:32 Initial Exhibit Script

06:26 Opposition and Controversy

07:15 Revisions and Criticisms

10:49 Air Force Association's Demands

11:59 Exhibit Cancellation

13:37 "Pale Shadow"

14:10 Reflecting on History and Censorship

20:55 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

DIVE DEEPER WITH CLUB ARCHIPELAGO 🏖️

Unlock exclusive museum insights and support independent museum media for just $2/month.

Join Club Archipelago

Start with a 7-day free trial. Cancel anytime.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

🎙️Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don't make it into the main show.

🎟️ Archipelago at the Movies, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies and other pop culture that reflect the museum world back to us.

✨A warm feeling knowing you're helping make this show possible.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 110. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsner. Museum Archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes. So let's get started.

By the late 1980s, the Enola Gay – the Boeing B-29 Superfortress that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima – had been sitting disassembled at the Smithsonian's Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland for decades. What was once a beautiful shiny machine with four powerful engines, just powerful enough with the right banking maneuver to escape the hell it unleashed, was scattered and severed, with disheveled tubes where the wings used to be and the remains of birds nests in the turrets.

Gregg Herken: It was shortly after I joined the museum and I went out to the restoration facility that the Smithsonian operates in Garber in Maryland. And they wanted to show me around. And since I was the new chairman of the Department of Space History, they said I could get into the fuselage of the Enola Gay.

This is Gregg Herken, retired professor of American Diplomatic History at the University of California, and Chairman of the National Air and Space Museum's Space History Division from 1988 to 2003.

Gregg Herken: Hello. My name is Gregg Herken. I'm a retired professor of American Diplomatic History at the University of California.

Herken was part of the team planning the exhibition at the National Air and Space Museum that would feature the restored Enola Gay and of course he accepted the invitation and climbed up into the fuselage.

Gregg Herken: So I sat in Tibbets' seat, in the pilot seat for a second, and then I sat in the bombardier seat. And off to the left was a panel that had, I think it was five toggle switches. And one of them had the label "bombs." And actually on the day of the Hiroshima mission, it would've said in a little tag underneath that "special."

Gregg Herken: But I remember just thinking that I could sit in, I'm sitting in that seat, I could just reach over and flip that switch. And that was the switch that released the Little Boy bomb on Hiroshima. And I thought there is bad juju with that. I did not want to touch it.

At the other end of that switch was about 80,000 people, civilians of Heroshima.

Herken was chosen to be part of the exhibition team by the museum's new director, Martin Harwit.

Gregg Herken: I've written about and taught the subject of nuclear history, and that's why I think Martin chose me to begin at last the effort to get the Enola Gay on exhibit.

Director Martin Harwit, who was hired in 1987, was a bit of a departure from previous National Air and Space Museum directors who tended to be pilots or astronauts. Harwit was an astrophysicist. Gregg Herken thought that it was a signal that the Smithsonian was interested in not just displaying but also interpreting the artifacts that represent the nation's past.

The planned exhibition intended to showcase the restored plane along with multiple perspectives on the first atomic bombings in warfare – including their devastating human toll. Harwit still has his first written notes from when he first arrived at the museum and started thinking about, which show his brainstorm about the historical context of the bombing of Hiroshima in the escalation of bombing in World War II.

"This is not an exhibit about the rights and wrongs of war," Harwit wrote in 1987, "about who started what, and who were the bad guys and who the good. It is about the impact and effects of bombing on people and on the strategic outcome of conflicts. Is bombing strategically effective? Are the costs worth the strategic gains? How great is human error?"

As part of the early planning process, Gregg Herken visited the Hiroshima Museum in Japan in 1991.

Gregg Herken: Yes, Martin asked me to go to Hiroshima. The exhibit was just getting started and really in the planning stages. And we wanted to see if we could get artifacts from the Hiroshima Museum. So I was sent there and I met with the director. And I was frankly a little concerned about how I'd be received, that the idea of shipping artifacts about the atomic bombing to the Smithsonian for an exhibit they didn't really know about. I thought they might be hostile or at least suspicious, but he was very welcoming. He was actually a survivor of the atomic bombing.

The director offered to loan the Smithsonian any of the artifacts his museum had in its collection, for as long as the "Enola Gay" remained on display at the National Air and Space Museum.

Gregg Herken: I do remember walking around the museum and there was one artifact that really stood out to me and we wanted to include it in the exhibit and we nicknamed it "the lunchbox" and it was just a ceramic tube that had contained rice and peas and it had been taken by a young girl to school as her lunch. And she obviously did not survive the bombing and the tube - you could see that the rice and the peas in it had been carbonized by the heat of the bomb.

Gregg Herken: So we were never going to show any terrible pictures of burned bodies. We didn't need to. That's all any adult had to do was to look at this lunchbox, at the carbonized food in the little ceramic tube to realize what had happened to that little girl and what it must have been like to have been on the ground at Hiroshima at that time.

Back in the United States the exhibition team continued developing their plans and by early 1994, the National Air and Space Museum had completed the script for the exhibit, now titled "The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb, and the Origins of the Cold War."

The team sought input from various stakeholders including veterans' groups and the Air Force Association. Initially, feedback seemed positive.

Gregg Herken: The Air Force Association is basically a private lobby based in Washington DC for the Air Force. And we knew – the museum, Martin knew that they might be early critics, so they were brought into the planning of the exhibit as was the Air Force historian, Richard Hallion, and were shown the original exhibit script. And I remember we had a meeting in the director's conference room and everybody seemed to be, "Well, this looks good."

But behind the scenes, an opposition was mobilizing.

Gregg Herken: And then they all left. And then we found out that the Air Force Association had hired a public relations firm in DC to essentially stop the exhibit going forward, at least as it was conceived. Even though there had been no criticism at the meeting itself.

This was the beginning of what would become a full-scale public relations battle over how the Enola Gay should be represented at the Nation

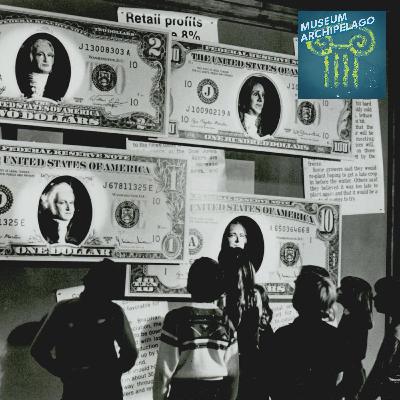

For the last few decades of the 20th century, if you visited Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, you could have been serenaded by a barbershop quartet of audio-animatronic portraits of America's founders as framed on U.S. currency. This was one of the many exhibits at Enterprise Square, USA, a high-tech museum dedicated to teaching children about Free Market Economics. The museum, which found itself out of money almost before it opened, shut down in 1999.

Barrett Huddleston first encountered these exhibits as a wide-eyed elementary school student in the 1980s, mesmerized by the talking puppets, giant electronic heads, and interactive displays that taught how regulation stifled freedom. Years later, he returned as a tour guide during the museum's final days, maintaining those same animatronics with duct tape and wire cutters, and occasionally being squeezed inside the two-dollar bill to repair Thomas Jefferson.

He joins us to explore this collision of education, ideology, and visitor experience, and how the former museum shapes his own approach to teaching children today.

Cover Image: Children watch audio-animatronic portraits of America's founders, as framed on U.S. currency, sing a song about freedom. [Photograph 2012.201.B0957.0912] (https://gateway.okhistory.org/ark:/67531/metadc465532/) hosted by The Gateway to Oklahoma History

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 Buzludzha Again (https://www.museumarchipelago.com/101)

00:46 Enterprise Square, USA

01:32 Barrett Huddleston

02:05 The Origins and Purpose of Enterprise Square

03:09 The Boom and Bust of Oklahoma's Economy

05:47 The Disney Connection and Animatronics

07:54 The Decline of Enterprise Square

11:42 Huddleston's Reflections on Education

13:41 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

DIVE DEEPER WITH CLUB ARCHIPELAGO 🏖️

Unlock exclusive museum insights and support independent museum media for just $2/month.

Join Club Archipelago

Start with a 7-day free trial. Cancel anytime.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

🎙️Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don't make it into the main show.

🎟️ Archipelago at the Movies, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies and other pop culture that reflect the museum world back to us.

✨A warm feeling knowing you're helping make this show possible.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 109. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsner. Museum archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes. So let's get started.

Buzludzha comes up a lot on Museum Archipelago. The monument was built in 1981 to look like a futuristic flying saucer parched high on Bulgarian mountains. Every detail of the visitor experience was designed to impress, to show how Bulgarian communism was the way of the future. Once inside, visitors were treated to an immersive light show, where the mosaics of Marx and Lenin and Bulgarian partisan battles were illuminated at dramatic moments during a pre-recorded narration.

But within a year of Buzludzha welcoming its first guests, all the way across the world in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, another museum opened to promote the exact opposite message. And it even had its own flying saucer connection.

Barrett Huddleston: The framing device of the museum is you have these two alien puppets that crash down in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and they need to get fuel for their spaceship so they can go back. I saw these animatronic puppets and I was like, oh, well this is just like Disney World, except they're talking about having to commodify their space technology so they can buy gold to put in their spaceship so they can get back to their planet or whatever.

This is Barrett Huddleston, who first visited Enterprise Square, USA as an elementary school student in the mid-1980s, and later worked there as a tour guide.

Barrett Huddleston: Hi, my name is Barrett Huddleston. I am an educational enrichment provider. I own a business called Mad Science of Central Oklahoma and Finer Arts of Oklahoma. I travel all over my state and a few others, delivering STEAM based workshops and assemblies to elementary school students. But In this instance, I also worked as a tour guide for Enterprise Square USA for over two years.

The story of Enterprise Square, USA begins in a boom, actually a few overlapping booms. In the late 1970s, oil had been found in the nearby Anadarko Basin and energy companies and money were rushing into Oklahoma City. As Sam Anderson puts it in his excellent book Boom Town, which is also where I first learned about this museum:

Excerpt from Boom Town: “Capitalism had blessed Oklahoma City, and the city wanted to express its thanks. At the height of the boom, local businessmen pooled their money to create a brand-new attraction that, even by the standards of Oklahoma City, was spectacularly strange. It was an interactive museum, a kind of secular shrine to free enterprise, designed to help local children appreciate the sanctity of capitalism.”

Barrett Huddleston: And I think at that point in the state of Oklahoma, it was one out of every six or eight people were either directly or indirectly employed by big energy in one respect. Now it's way, way, way lower than that. And we've got a much more diversified economy. But Enterprise Square was also attached to an evangelical Christian university at a time where there was a lot of deregulation in education because of the Reagan administration. So if you were evangelical. And if you were pro laissez faire capitalism then you were definitely going to get the kind of funding that it would take from the donor class to build a museum for children that was pro free market.

Huddleston also turned me on to a different kind of boom – the baby boomer’s children were beginning to go to college around this time too. Echo booms are always more diffuse than the original boom, since people choose to have children at different times. But pretty much any college or university in the country, including Oklahoma Christian University, which hosted the museum on their campus, could expect increasing enrollment year after year no matter what they did.

Barrett Huddleston: Enterprise Square opened in 1982, and I believe as early as first, second, or third grade, school trips were being taken there, and I must have been about seven or eight years old. So much of my childhood education was, sort of, that curriculum that was created between the Great Society and the Reagan administration. So a lot of the education that I got as hand me down education from the previous generation was very pro regulation, very pro safe market approaches, et cetera, et cetera.

And I think that by the time that Enterprise Square came along, it was like, well no, we need to, we need to unlearn what these kids have learned in school and then retrain them about how bad regulation can be and how wonderful a free market can be and how they need to really pay attention to the weather forecast if they're going to make their own lemonade stands and that kind of thing.

And it’s clear from the contemporary news coverage, like this one from Action 4 in Oklahoma City, that Enterprise Square, USA represented something different.

Contemporary News Coverage: This is the first group to tour the nation's only museum devoted solely to free enterprise. The 15 million Enterprise Square, USA has been six years in the making. Every penny and minute of time spent shows up in a big way on the inside. It's an economic learning experience. And with a touch of animation. It's Disneyland in a classroom. But there’s more. These digital readouts update all sorts of nationwide figures, minute by minute, on employment, taxes, traffic deaths, and so on. Dan Slocum, Action 4 at Enterprise Square.

Disney comes up a lot in these discussions about Enterprise Square, USA. Epcot, Disney’s second park in Florida, opened just one month before Enterprise Square in October 1982.

Barrett Huddleston: I think at that point, one of the mechanics that designed Enterprise Square was an Imagineer from Epcot Center.

Even the museum’s name evokes “Main Street, USA”, a Disney themed area that’s an amalgamation of feelings or memory or history rather than a specific place. In the late 1950s, eyeing expansion of his Disneyland park, Walt Disney developed -- but never built -- a spur off of Main Street, USA that was to be called Edison Square, dedicated to all things progress and industry. It’s hard not to see the connection.

Another connection is the audio-animatronics. Reading from Boom Town again:

Excerpt from Boom Town: “Next to the world's largest cash register, four enormous paper bills hung on the wall, and their giant Founding Father heads sang a barbershop quartet about freedom, the animatronic faces jerking around like figures in a Chuck E. Cheese band.”

[Singing barbershop quartet]

Barrett Huddleston: You've got a barbershop quartet of sort of the hall of president's heads of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, singing about freedom, freedom, freedom. they're inside the paper currency. It's hollowed out. When I was, and. a tour guide. I remember on several occasions Thomas Jefferson had a tendency to just break down by that time because it had been 15 or 20 years. So because I was the smallest tour guide, they would remove his head and shove me through his 2 bill and have me get back there with a pair of needle nose pliers.

Ian Elsner: Oh my god.

Barrett Huddleston: Cut the blue wire so that Thomas Jefferson could s

The tension is right there in the name of the Museum of Utopia and Daily Life. It sits inside a 1953 kindergarten building in Eisenhüttenstadt, Germany, a city that was born from utopian socialist ideals. After World War II left Germany in ruins, the newly formed German Democratic Republic (GDR) saw an opportunity to build an ideal socialist society from scratch. This city – originally called Stalinstadt or Stalin’s city – was part of this project, rising out of the forest near a giant steel plant.

The museum's home in a former kindergarten feels fitting – the building's original Socialist Realist stained glass windows by Walter Womacka still depict children learning and playing with an almost religious dignity. But museum director Andrea Wieloch isn't as interested in the utopian promises as she is in the "blood and flesh kind of reality" of life in the GDR. The museum's collection of 170,000 objects, many donated by local residents who wanted to preserve their history, tells the story of the GDR through the lens of how people actually lived during the country's 40-year existence.

The approach of the Museum of Utopia and Daily Life is to treat the history of the GDR as contested, full of stories and memories that resist simple narratives. In this episode, Wieloch describes how her approach sets the museum apart from other GDR museums in Germany including ones that cater to more western audiences.

Image: Socialist Realist stained glass windows by Walter Womacka welcome visitors in this former kindergarten.

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 Post-War Germany and the GDR's Vision

00:59 The Planned City of Eisenhüttenstadt

3:00 Andrea Wieloch

03:15 The Museum of Utopia and Daily Life (https://www.utopieundalltag.de/en)

03:56 Daily Life in the GDR

07:35 GDR History in modern Germany

14:43 Future Plans for the Museum

17:44 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

DIVE DEEPER WITH CLUB ARCHIPELAGO 🏖️

Unlock exclusive museum insights and support independent museum media for just $2/month.

Join Club Archipelago

Start with a 7-day free trial. Cancel anytime.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

🎙️Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don't make it into the main show.

🎟️ Archipelago at the Movies, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies and other pop culture that reflect the museum world back to us.

✨A warm feeling knowing you're helping make this show possible.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 108. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsener. Museum archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes. So let's get started.

After World War II, all of Germany was in ruins. Almost nothing was left standing after 12 years of Nazi rule and 6 years of war. Mass migration, hunger, and homelessness defined the immediate post-war period as millions of displaced people sought to rebuild their lives among the rubble.

For the newly formed German Democratic Republic or GDR, the chance to start over – and demonstrate the utopia of the socialist system – took on a great importance. The East German government saw urban planning as a way to both solve the housing crisis and showcase socialist ideals through modern, centrally planned cities built from scratch. I visited one of these planned cities about an hour and a half east of Berlin.

Andrea Wieloch: Where we are sitting now was basically forest 75 years ago, and then they decided to plant a steel factory and a city around it. It was back in the days where there was really everything destroyed by war. An island of a real utopia with nice housing and facilities for everyone. So people from all over GDR came here and when the city was first founded, it was called Stalinstadt. So, “city of Stalin”.

Stalinstadt, which started being built in 1951, is now called Eisenhüttenstadt, which literally means Iron Hat City for the steel plant. Planning and building a new city and a steel factory in a place that was just a forest during the Nazi regime was a sharp break with the past – the planned city reminds me of parts of Bulgarian cities also built in the socialist times, and unlike most places I’ve visited in Germany, I’m not immediately on the lookout for dark signs of the Nazi past. I can imagine the relief of this place for the first people who moved here. Maybe, for a moment, it did feel like utopia.

Of course, this utopia didn't actually happen, no utopia has. But the GDR lasted about 40 years and those 40 years covered a lot of daily life. I'm here to visit a museum that puts the tension of utopia right in the name: the Museum of Utopia and Daily Life.

Andrea Wieloch: I do like the space in between utopia and daily life. That is my focus, that tension or ambivalence. And I'm frankly not really interested in utopia, I think, because it's a mind fabricated thing and I do like the blood and flesh kind of reality.

This is Andrea Wieloch, director of the Museum of Utopia and Daily Life.

Andrea Wieloch: Hello, my name is Andrea Wieloch. I am a German museum professional and I am the director of the Museum of Utopia and Daily Life.

The museum – a kind of documentation center of everyday life in the GDR – is built inside a former kindergarten which opened in 1953. The central staircase still features the original, very colorful, stained glass windows by Socialist Realist artist Walter Womacka depicting children learning and playing with an almost religious dignity.

Wieloch says that a big part of the collection comes from a public announcement for people to bring in objects that they wanted to save. Today the collection has 170,000 objects of everyday life and of every aspect of GDR life. The permanent exhibition, which opened in 2012, called Everyday Life: GDR, uses these objects to give the visitor an introduction to politics, society and everyday life in the country.

Right inside the entrance to the museum, under the stained glass kindergarten scene, is one of these objects: a rusty TV antenna.

Andrea Wieloch: The antenna you see in the front is a really great example for a life hack, basically, because someone did it himself.

People living in Eisenhüttenstadt could fashion an antenna to get western television broadcasts in part because of their proximity to West Berlin and favorable terrain. It started as something you could do if you were brave enough to do something forbidden, but by the 70s, it became a special privilege.

Andrea Wieloch: One privilege you would get here but only starting in the late 70s was getting West TV and radio, which was forbidden. But they needed workers, so that was a privilege here, not in other parts of the country.

Amazing. Well, it also illustrates, so before it was a privilege, it was a hack. And I feel, feel like that is the bridge between utopia and daily life. It's because , in a true utopia, there would be nothing to hack because everything is already perfect.

Andrea Wieloch: Yeah and that's a two-way street. You go from hacking to utopia again, because of course in the 40 years that the GDR was existing, there were really waves. And you've seen upstairs the new exhibition we are putting on with plastic furniture, that was a wave of utopia again, in order to also make people not jealously look at the West, but really a propaganda to really tell we are able here, we are future, we can send a man to the moon as well, kind of, you know.

The privileges associated with working in the Steel Factory is an example of the centrality of work in the way this utopia was structured.

Andrea Wieloch: All aspects of life in the socialist society were organized around work. Which means your housing was organized around work. The way you made holidays, where you would put your children to kindergarten or school, how you would spend your free time. There were club houses all over the city. There were artists coming into the factories and the worker was very well taken care of in the socialist society. And here in that city, it meant you had a beautiful flat, you had all the facilities that would really enable you to be a good worker, be at work and not think of anything else.

Wieloch was born in 1983 in the GDR, and so has a better memory of the period after 1989 when the Berlin Wall fell, the GDR dissolved, and the process of German reunification began.

Andrea Wieloch: I was six years when the Wall came down and I was living with my family at the Polish border, so really far away from what was happening. And I remember my parents sitting in front of the TV and relatives coming in and that it was something special, I remember that. But besides that, I'm more shaped by the reality of the 90s, mass unemployment and lots of friends leaving the area with their families in order to look for better places and a more prosperous life.

The Museum of Utopia and Daily Life, and the way it presents the history of the GDR, is unique in Germany.

Andrea Wieloch: Yeah, I think we are talking about a very young history. And it's – I hope I get the word right – it's a contested history. It's one that is not set yet. Where we know no history is set, but as soon as people who can talk about the history aren't there anymore, we rely on what we by then have agreed upon. And there are very different ways in which the history of GDR got told within the last, let's say, 30 years.

Wieloch says that she’d classify four types of museums that interpret the history of the GDR in modern Germany. The first is the entertaining museum, places like the slick GDR Museum in Berlin which caters to int

In November 2021, an extremely rare first printing of the U.S. Constitution was put up for auction at Sotheby's in New York, attracting a unique bidder: ConstitutionDAO, a decentralized autonomous organization. This group had formed just weeks earlier with the sole purpose of acquiring the Constitution – and would not have been possible without crypto technology.

While museums and crypto don't commonly coexist at the moment, they may increasingly intersect in the future. They actually address similar fundamental issues: trust and historical accuracy. Both can help answer the question: what really happened? To explore this overlap, we speak with Nik Honeysett, CEO of the Balboa Park Online Collaborative in San Diego, who helps trace the story of ConstitutionDAO's bid for the Constitution. We explore key crypto concepts like blockchains and smart contracts, and how they might apply to the wider museum world – particularly around questions of provenance and institutional trust.

Image: Nicolas Cage in 2004's National Treasure. Supporters of ConstitutionDAO drew parallels between his character's fictional theft of the Declaration of Independence and the DAO's real-life attempt to purchase the Constitution.

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 Auction of the U.S. Constitution (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1TBa-9Lx3vc)

00:43 Constitution DAO (https://www.constitutiondao.com)

01:36 The Role of Governance Tokens

02:02 Nik Honeysett (http://honeysett.com)

02:45 Balboa Park Online Collaborative (https://bpoc.org/)

04:29 Museums and Crypto

05:24 Blockchain and Provenance

07:40 Smart Contracts and Museum Governance

09:56 The Outcome of the Auction

11:58 Museums as Trustworthy

14:00 Museum Archipelago Ep. 39. Hans Sloane And The Origins Of The British Museum With James Delbourgo (https://www.museumarchipelago.com/39)

16:41 Conclusion and Future of Crypto in Museums

17:44 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

Museum Archipelago is a tiny show guiding you through the rocky landscape of museums. Subscribe to the podcast via Apple Podcasts (https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/museum-archipelago/id1182755184), Google Podcasts (https://www.google.com/podcasts?feed=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cubXVzZXVtYXJjaGlwZWxhZ28uY29tL3Jzcw==), Overcast (https://overcast.fm/itunes1182755184/museum-archipelago), Spotify (https://open.spotify.com/show/5ImpDQJqEypxGNslnImXZE), or even email (https://museum.substack.com/) to never miss an episode.

DIVE DEEPER WITH CLUB ARCHIPELAGO 🏖️

Unlock exclusive museum insights and support independent museum media for just $2/month.

Join Club Archipelago

Start with a 7-day free trial. Cancel anytime.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

🎙️Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don't make it into the main show.

🎟️ Archipelago at the Movies, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies and other pop culture that reflect the museum world back to us.

✨A warm feeling knowing you're helping make this show possible.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 107. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

In November 2021 an extremely rare, first printing of the U.S. Constitution was available to buy at auction. While the item was special – only 13 copies existed according to the auction house – the bidders were the usual assortment of wealthy individuals.

Auctioneer: “And now let's begin the auction. Lot 1787. The United States Constitution. We’ll start the bidding here at 10 million dollars. 11 million.12 million ”

Except for one. Among the individuals trying to buy the Constitution was not an individual at all. It was a new kind of organization – a decentralized autonomous organization better known as a DAO. This organization, ConstitutionDAO, had formed just a few weeks earlier for this exact purpose – to buy the Constitution.

I remember the memes – backers of the project posted images of Nicolas Cage in 2004’s National Treasure, drawing parallels between his character’s fictional theft of the Declaration of Independence and this real-life attempt to purchase the Constitution.

In the weeks leading up to the auction, thousands of people contributed money to ConstitutionDAO using the cryptocurrency Ether. That money funded the bid – the amount ConstitutionDAO could pay to try to acquire the constitution. What the contributors were actually buying was a so-called governance token: governance rights, the ability to vote on what to do with the Constitution, specifically, which museum to send it to, and what text would be displayed next to the document in the gallery.

Nik Honeysett: The ConstitutionDAO is an interesting example of the public claiming back ownership of a document that, you know, really should be owned by the public. And I think, you know, that's the challenge for museums.

This Nik Honeysett, CEO of the Balboa Park Online Collaborative in San Diego, California.

Nik Honeysett: Hello, my name is Nick Honeysett. I'm CEO of the Balboa Park Online Collaborative, known as BPOC. We are a nonprofit, technology and strategy company located in San Diego's Balboa Park, which is a cultural park of about 30 institutions. And we provide a range of services on a shared service model. And we also work with museums across the U. S. and outside the U.S. largely providing digital strategy, to help organizations figure out what they should be trying to figure out as we enter a more prevalent digital world.

The genesis of BPOC came in the early 2000s. Because there’s such a high density of museum institutions in San Diego’s Balboa Park, museums realized they could pool their resources and they wouldn't need to start from scratch to build each individual institution’s technology stack,

Nik Honeysett: It's a very dense cultural environment. Some of the institutions are actually physically in the same building. There has to be an opportunity for us to do this collaboratively. To create a team of IT professionals that would provide IT support. So essentially a kind of separate IT service department that would serve the institutions. That they would pay for those services. So you were gaining the economy of scale. And so we did a lot of, in the early days, a lot of digitization, kind of collaborative digitization projects. We have a couple of collaborative infrastructure applications like digital asset management. And really the benefit is there's an altruistic need. So the larger institutions are offsetting the costs for some things for the smaller institutions. And we do serve some volunteer-only institutions and they have access to the same level of IT service and support that the larger ones do.

While BPOC’s shared service model pools resources from lots of different museums, it still operates as a normal organization with a board of directors and a CEO making decisions and some sort of legal counsel and a sustained collaborative relationship with museums. The focus is technology, but the methods are more traditional.

ConstitutionDAO, by contrast, was a spontaneous, decentralized effort to acquire a historical document that probably wouldn’t have been possible without crypto technology.

I’ve been working on this episode about crypto in museums for years: I recorded this interview with Honeysett in March of 2022, two and a half years ago. Most museum people I know are reluctant to talk about crypto for various reasons: concerns about the massive energy use of some blockchains, how from the outside, it looks like speculative hype cycle, and – maybe most importantly – there’s a wide cultural gap between the centralization of museum power and the decentralized ideals of blockchain culture. “Move fast and break things” doesn’t sound too appealing if your job is to make sure the ancient vases don’t shatter.

But I will argue that museums and crypto have some interesting overlaps. Museums and crypto both address the same fundamental issue: trust, and they seek to answer the same question: what happened?

Blockchains keep an unchangeable record of what happened, stored not in a warehouse or a datacenter, but distributed without a point of control or a single point of failure. The first and most famous use for these blockchains is to power cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, but they can do a lot of things, like, for example, provenance.

Provenance is the record of ownership and history of an item, tracking where it has been and who has owned it over time. Right now institutions like museums and auction houses handle provenance but maybe there are better ways.

Nik Honeysett: Provenance is extremely important in the museum world and I think provenance seems to be the ideal application for blockchain. Here is the irrefutable, definitive, provenance of this work. And we saw a huge issue with provenance, which is the Nazi era provenance issue, you know, when a lot of works of art disappeared from the record because they were confiscated by the Nazis during World War II. And there's been a lot of research to reestablish the true provenance of works of art and repatriate them, in certain circumstances. Collections held in the public trust need to be presented to the public. If you look at what really engages audiences, there are some emerging strategies that think about collection objects, as a sequence of experiences. The first experience is it was created. A painting was painted. The second experience is maybe shown in a show. The third is that it was sold to its first owner. And then it was transported and then it was acquired by a museum or whatever it is. So you have these sequences of experiences and the painting interacting with a whole set of things, again, all which happened in a particul

I remember visiting – and loving – The Streets of Old Milwaukee exhibit at the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) as a child. Opened in 1965, it’s an immersive space with cobblestone streets and perfect lighting that evokes a fall evening in turn-of-the-20th-century Milwaukee. The visitor experience isn’t peering into a diorama, it’s moving through a diorama, complete with lifelike human figures.

And I’m not the only one with fond memories. When the museum announced that the exhibit would not move over to the planned new museum down the street, the public reacted negatively. Dr. Ellen Censky, president and CEO of the MPM, describes the reasons why the museum can’t – and most interestingly shouldn’t – move The Streets of Old Milwaukee exhibit. It’s a story involving cherished memories, the distinction between collections and exhibits which isn’t always at the top of visitors’ minds, and public trust.

In this episode, we explore why the Milwaukee Public Museum decided to move (it’s the fourth relocation in its history) and Milwaukee Revealed, the planned new immersive gallery that will be the spiritual successor to The Streets of Old Milwaukee, which will cover a much larger swath of the city’s history. Plus, we get into the meta question of whether museums are outside of the history they are tasked with preserving.

Image: Bartender in Streets of Old Milwaukee at Milwaukee Public Museum. Photo by Flickr user JeffChristiansen (https://www.flickr.com/photos/jeffchristiansen/20054374028/in/photolist-G3EgWm-vwai8W-wy9puA-wyiczB-wQ49p3-vTHZv5-vTJ8gW-wy8HgG-wQ1Yvu-wRgrox-vTJC95-wygrep-wygP9B-wQLb7T-wy8UHs-vTTe2e-wQ25WW-wNrDDh-vTTh5D-vTTkQV-vTJ1Ab-wygSr8-wRgpXX-wQ1Rsb-wy8PBW-vTJ3Vw-wyfXCH-wy9r8A-vTSPUH-wy9goN-wNqT5N-wy9DFb-vTT87t-wRgCsr-wygXRg-vTTGDD-vTTKzZ/)

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 The Streets of Old Milwaukee’s 2015 Renovation

01:17 The Streets of Old Milwaukee’s Visitor Experience

03:40 Dr. Ellen Censky, President and CEO of the Milwaukee Public Museum

04:10 The Decision to Move the Museum

04:45 AAM Accreditation (https://www.aam-us.org/programs/accreditation-excellence-programs/accreditation/)

06:21 The Current Museum

07:42 Funding the New Museum

08:55 Milwaukee Revealed

11:14 Milwaukee WTMJ4 from January 11th, 2023 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kcVPpHX9FxY)

11:40 The distinction between collections and exhibits

12:45 “We owe future museum goers the opportunity to see something different”

13:44 Local Talk Radio Coverage

14:07 Museum Designers

15:29 Closing Thoughts and the “Next Best Thing”

17:00 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

Museum Archipelago is a tiny show guiding you through the rocky landscape of museums. Subscribe to the podcast via Apple Podcasts (https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/museum-archipelago/id1182755184), Google Podcasts (https://www.google.com/podcasts?feed=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cubXVzZXVtYXJjaGlwZWxhZ28uY29tL3Jzcw==), Overcast (https://overcast.fm/itunes1182755184/museum-archipelago), Spotify (https://open.spotify.com/show/5ImpDQJqEypxGNslnImXZE), or even email (https://museum.substack.com/) to never miss an episode.

DIVE DEEPER WITH CLUB ARCHIPELAGO 🏖️

Unlock exclusive museum insights and support independent museum media for just $2/month.

Join Club Archipelago

Start with a 7-day free trial. Cancel anytime.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

🎙️Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don't make it into the main show.

🎟️Archipelago at the Movies a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies and other pop culture that reflect the museum world back to us.

✨A warm feeling, knowing you're helping make this show possible.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 106. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

I first learned about the impending closure of the popular The Streets of Old Milwaukee exhibit at the Milwaukee Public Museum, or MPM, back in 2015. The news came in the form of an email from a family member who had lived in the Milwaukee area her whole life. It was only a year after I started working in the museum world, and she was eager to talk to me – then a newly-minted museum professional! -- about what a colleague had told her: that Streets of Old Milwaukee, which had been there quote "forever", was about to close.

She wrote, "I was upset since this was always one of my favorite exhibits (along with the bison hunt/rattlesnake diorama, of course)."

A little later in the email she expresses a sense of relief learning that the exhibit wasn't closing permanently. The confusion turned out to be a renovation that would temporarily close the exhibit for about six months and reopen in December 2015. The panic faded a bit.

The Streets of Old Milwaukee, which opened in 1965, is beloved for good reason: it’s an immersive space with cobblestone roads and perfect lighting that evokes a fall evening in turn-of-the-20th-century Milwaukee. The visitor experience isn’t peering through a diorama, it’s moving through a diorama, complete with lifelike human figures. Visitors go in and out of inviting storefronts, old-timey police boxes, and a candy shop.

I used to visit as a kid and I loved how it transported me. I couldn’t say exactly where it transported me, but it was exciting. I remember staring at a figure of a grandma – who everyone just called granny – in a rocking chair on a front porch and trying to figure out the mechanism by which she was rocking.

Today’s guest, Dr. Ellen Censky, told me in 2015 when she was academic dean of the Milwaukee Public Museum, the MPM, on one of the first episodes of Museum Archipelago, that this attention to detail was one of the reasons why the museum punches above its weight.

Dr. Ellen Censky: It's an experience that you get when you're here. It's this immersive experience. And so we really need to understand that as we move forward to make sure that as we enhance things, that we don't take away what people love.

That skittishness over a beloved exhibit closing, or even changing, was apparent in the way that the museum presented their 2015 renovation plans. Listen to Al Muchka, then Curator of History Collections at the MPM, describe the renovation in an official video:

Al Muchka: “Don't you change my streets of old Milwaukee. That ownership came through and we understood that. I mean, many of the people here in the museum that work here, we, we grew up here, so we understand the idea of this is our place. These are our things. So when people would call us to say, don't change my exhibit, we get it.”

But that was 2015. Now, almost 10 years later, that fear has come true.

In a few years, The Streets of Old Milwaukee will close for good – not just for a temporary refurbishment.

And, predictably, the reaction has not been good.

Dr. Ellen Censky: Hi, my name is Ellen Censky and I am president and CEO of the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Today, Dr. Censky is president and CEO of the MPM. The Streets of Old Milwaukee is closing for good because the museum itself is moving to a new building and the museum says it can’t move the exhibit as it is since it’s literally built into the old building – and even if they could, they probably wouldn’t.

So let’s explore each in turn.

Dr. Censky says that the decision to move the museum was triggered by the American Alliance of Museums, or AAM’s accreditation process. AAM’s accreditation process is a set of industry standards that is effectively shorthand for institutional credibility. The MPM first gained accreditation in 1972 and the accreditation process should be done about every ten years. If a museum is not accredited, it might have difficulty winning grants or handling loan agreements for traveling exhibits.

Dr. Ellen Censky: Back in 2016, as we were approaching reaccreditation for the museum, we were reflecting back on the past reaccreditation and in that reaccreditation, they had cautioned us that the condition of the building was not adequate for housing the collections. It was deteriorating to the extent that it could be causing harm to the collections. And, of course, That's what we are, is a collections based museum. And they said you need to do something about this. And, of course when we were thinking about reaccreditation which was coming up in 2020.

The building continued to deteriorate. It had not gotten better. And it had built up a significant amount of deferred maintenance. The building is not owned by the museum. The building is owned by the county. And the county has financial challenges as they own many, many buildings and have lots of things that they need to take care of.

And so building maintenance for the museum was just not a high priority for them. So we headed into this study to see what we could do should we invest in money. Putting money into this building to bring it up to AAM standards and thereby receive accreditation, or should we build a new building?

The museum decided to build a new building. This annoyed me at first. Surely any maintenance fixes would be cheaper and – well – less wasteful than building a new building?

I’m fond of the current building, on 800 W Wells St in Milwaukee. In addition to trying to figure out how the granny rocked, one of my formative museum experiences was noticing how the floor ramped down in the Living Oceans exhibit as we went deeper underwater. I remember feeling nervous as the lighting changed and I descended the depths. It’s all very cool and effective.

But you can find videos online highlighting the poor shape of the building itself. Not so much on the exhibit floors, which again, are awesome, right down to the rattlesnake button on the Bosion Hunt diorama. But down in the basement col

While working at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History during the pandemic, Dr. Morgan Rehnberg (https://www.morganrehnberg.com) recognized the institution's limited capacity to develop new digitals exhibits with the proprietary solutions that are common in big museums. This challenge led Rehnberg to start work on Exhibitera (https://exhibitera.org), a free, open-source suite of software tools tailored for museum exhibit control that took advantage of the touch screens and computers that the museum already had.

Today, as Vice President of Exhibits and Experiences at the Adventure Science Center in Nashville, Rehnberg continues to refine and expand Exhibitera, which he previously called Constellation. The software is crafted to enable institutions to independently create, manage, and update their interactive exhibits, even between infrequent retrofits. The overarching goal is to make sure that smaller museum’s aren’t “left in the 20th century” or reliant on costly bespoke interactive software solutions.

Exhibitera is used in Fort Worth and Nashville and available to download. In this episode, Rehnberg shares his journey of creating Exhibitera to tackle his own issues, only to discover its broader applicability to numerous museums.

Image: Screenshot from a gallery control panel in Exhibitera

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 Computer Interactives in Museums

01:00 Dr. Morgan Rehnberg (https://www.morganrehnberg.com)

01:40 Rehnberg on Cassini (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cassini–Huygens)

02:14 The Adventure Science Center in Nashville (https://www.adventuresci.org)

03:30 A Summary of Computers in Museums (https://www.museumarchipelago.com/103)

05:00 Solving Your Own Problems

06:30 Exhibitera (https://github.com/Cosmic-Chatter/Exhibitera)

07:45 “A classroom teacher should be able to create a museum exhibit”

08:30 Built-In Multi-Language Support

09:30 Open Source Exhibit Management (https://github.com/Cosmic-Chatter/Exhibitera)

10:30 Why Open Source?

12:30 Go Try Exhibitera for Your Museum (https://cosmicchatter.org/constellation/tutorials.html)

13:20 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club/)

Museum Archipelago is a tiny show guiding you through the rocky landscape of museums. Subscribe to the podcast via Apple Podcasts (https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/museum-archipelago/id1182755184), Google Podcasts (https://www.google.com/podcasts?feed=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cubXVzZXVtYXJjaGlwZWxhZ28uY29tL3Jzcw==), Overcast (https://overcast.fm/itunes1182755184/museum-archipelago), Spotify (https://open.spotify.com/show/5ImpDQJqEypxGNslnImXZE), or even email (https://museum.substack.com/) to never miss an episode.

Support Museum Archipelago🏖️

Club Archipelago offers exclusive access to Museum Archipelago extras. It’s also a great way to support the show directly.

Join the Club for just $2/month.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don’t make it into the main show;

Archipelago at the Movies 🎟️, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies that take place at museums;

Logo stickers, pins and other extras, mailed straight to your door;

A warm feeling knowing you’re supporting the podcast.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 105. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsner. Museum Archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes, so let's get started.

I’ve spent most of my career building interactive exhibits for museums. These are all visitor-facing: touchscreens for pulling up information or playing games based on the science content, projection walls for displaying moving infographics, and digital signage for rotating through ticket prices or special events.

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg: Well I think most computer interactives in museums are pretty bad. And I don't think that's because they were necessarily bad when they were first installed, but major exhibitions can last for 10, 15, 50 years, and it's often quite difficult to go back and retrofit and improve something like technology as time goes on.

This is Dr. Morgan Rehnberg, Vice President of Exhibits and Experiences at the Adventure Science Center in Nashville. Rehnberg offers that long-term maintenance is the reason most computer interactives in museums are pretty bad – and that is kindly letting us programmers off the hook for the other reasons why computer interactives can be bad. But I agree with him. When I build an interactive exhibit for a museum, I’m optimizing for opening day, and generally leave it up to the museum to maintain it for years after.

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg: Hello, my name is Dr. Morgan Rehnberg and I'm the Vice President of Exhibits and Experiences at the Adventure Science Center in Nashville.

I actually started my journey in science. I did my PhD work in astronomy. And I worked as part of NASA's Cassini mission, which studied Saturn for many years. And it got to a point where we sort of dramatically crashed the spacecraft into Saturn. And I realized at that point that I was going to need to find something else to do. And kind of thinking back,I realized that I had been having more fun when talking about the work that we were doing than actually doing it.

So I started to look and see how I could turn that into a career, and I ended up in Texas at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History and spent five lovely years there, including the time during the pandemic. And as the world started coming back,, I felt like it was time for a change of scenery and made the switch to Nashville. And I've been thrilled to be here at the Science Center for just under two years now.

Like many science museums, we focus on families with young kids, full of hands-on exhibits, exploring all the areas of STEM. And we serve the public, we do field trips, we run summer camps, all the things that science museums do. But we do it with a team that's maybe a little bit smaller than you would have at some of the big museums, in cities like New York or San Francisco or Chicago.

And that team size becomes relevant to the long-term maintenance of computer interactives.

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg: Here in Nashville. We have touch screens that we installed in 2008 that still do everything that they did then, but what the world around them has done since 2008 has changed a lot. And so while the experience is the same as it always was, the expectations of visitors coming in are quite a bit different.

On the back end, most of the computers running in museum galleries are general purpose computers, normal PCs running Linux or Windows. Similarly, the interactive exhibit software running on them are often built using game development engines like Adobe Flash or Unity.

There are advantages and disadvantages to building on top of these platforms. On the one hand, museums get to benefit from the rapid iteration of consumer technology. On the other hand, these tools that were not designed for the museum environment, so there are all sorts of situations where you end up working at cross-purposes with your tools.

A good example: any general purpose computing environment needs to have an easy way, in fact many easy ways, for a user to close an app. However, in a museum's touchscreen setup, you wouldn't want visitors to be able to close the exhibits, so you have to invent ways to prevent that .And every time Windows updates, you might have to do it all over again in a different way.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve walked out of a museum server room, satisfied with a job well-done, only to notice that a smart kid on the gallery floor has figured out how to close my interactive software and has pulled up a game of solitaire. And let me tell you – solitaire is the best case scenario. If that computer is connected to the internet, things can get a lot worse.

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg: I think a lot of us who work in medium or larger museums forget that by number, the vast majority of museums in this country or anywhere in the world have staffs of one or two or three and have budgets measured in, you know, thousands of dollars or tens of thousands of dollars.

Those places are never going to be able to afford the sorts of bespoke custom software that you might see at Boston Museum of Science. They're just never going to have that. But they shouldn't be left in the 20th century of all we've learned about the value of interactivity in museums.

So while working at the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History during the covid pandemic, Rehnberg started looking for a solution.

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg: As I was looking at sort of this big idea of what could be a piece of software that would solve all my problems.I started looking at that and sort of subdividing those problems. And one category of problem was wanting to have new touch sensitive, visitor facing things. And I didn't have the money during the pandemic to hire a vendor to redo all the things everywhere. The second piece of it was how can I, with greatly reduced exhibit technician staff, manage all of these things with the least amount of effort. Because I know if I have one tech who needs to cover the whole building, they can't spend a bunch of time debugging a thing after a visitor has smashed the screen 50,000 times and frozen the computer. Those two parallel ideas have lent themselves to the structure of Constellation.

Constellation is the name of the free and open source exhibit control software that Rehnberg developed. Today, he calls it Exhibitera, but you still might catch him referring to it by its old name. And those two parallel ideas have turned into a suite of tools that a museum can use to build their own inter

The Murney Tower Museum (https://www.murneytower.com) in Kingston, Ontario, Canada is a small museum. Open for only four months of the year and featuring only one full-time staff member, the museum is representative of the many small institutions that make up the majority of museums. With only a fraction of the resources of large institutions, this long tail distribution of small museums offers the full range of museum services: collection management, public programs, and curated exhibits.

Dr. Simge Erdogan-O'Connor (https://linktr.ee/simgeerdogan) has dedicated her studies to understanding the unique dynamics and challenges faced by small museums, and is also the Murney Tower Museum’s sole full-time employee.

In this episode, Dr. Erdogan-O'Connor describes the operation of The Murney Tower Museum, discusses the economic models of small museums, and muses on what small museums can teach larger ones.

Image: Murney Tower Museum

Topics and Notes

00:00 Intro

00:15 Understanding the Landscape of Small Museums

02:38 Dr. Simge Erdogan-O'Connor (https://linktr.ee/simgeerdogan)

03:00 Murney Tower Museum (https://www.murneytower.com/)

08:29 Overcoming Challenges with Digital Solutions

09:46 What Big Institutions Can Learn from Small Museums

09:54 The Power of Local Connections in Small Museums

13:20 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖 (http://jointhemuseum.club)

Museum Archipelago is a tiny show guiding you through the rocky landscape of museums. Subscribe to the podcast via Apple Podcasts (https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/museum-archipelago/id1182755184), Google Podcasts (https://www.google.com/podcasts?feed=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cubXVzZXVtYXJjaGlwZWxhZ28uY29tL3Jzcw==), Overcast (https://overcast.fm/itunes1182755184/museum-archipelago), Spotify (https://open.spotify.com/show/5ImpDQJqEypxGNslnImXZE), or even email (https://museum.substack.com/) to never miss an episode.

Support Museum Archipelago🏖️

Club Archipelago offers exclusive access to Museum Archipelago extras. It’s also a great way to support the show directly.

Join the Club for just $2/month.

Your Club Archipelago membership includes:

Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don’t make it into the main show;

Archipelago at the Movies 🎟️, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies that take place at museums;

Logo stickers, pins and other extras, mailed straight to your door;

A warm feeling knowing you’re supporting the podcast.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 104. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

View Transcript

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsner.

Museum Archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is rarely longer than 15 minutes, so let's get started.

Let’s say you sorted every museum on earth in order by the number of yearly visitors.

At one end, with yearly visitor numbers in the millions, would be large, recognizable institutions – places like the British Museum in London. There’s a cluster of these big institutions, but as you go further along the ordered list of museums, the visitor numbers start to drop.

At some point during these declining visitor numbers, you reach small museums. Exactly where in the order you first reach a small museum doesn’t really matter – one definition of small museums from the American Association of State and Local History is simply: “If you think you’re small, you’re small.” You could do the same sort by number of staff members or by operating budget – the effect would be more or less the same. The point is that once you reach the threshold where small museums begin, you still have the vast, vast majority of museums to go.

Simge Erdogan-O'Connor: You just realize how many small museums are there in the world. Unbelievable numbers, right? They're everywhere and they hold such an important space in local cultural landscapes. Even if I dare to say more than large institutions.

The sorting exercise illustrates a long tail effect – each small museum, while attracting fewer visitors individually, collectively hosts an enormous number of visitors. There’s just so many of them. The long tail effect was coined in 2004 to describe economics on the internet: the new ability to serve a large number of niches in relatively small quantities, as opposed to only being able to serve a small number of very popular niches.

But unlike the economics of the internet, where distribution costs are minimal, small museums face the challenge of fulfilling nearly all the responsibilities of larger museums without any of the benefits of scale.

Simge Erdogan-O'Connor: What fascinates me most about small museums is despite being so small, they offer almost everything you can find in a large museum, Ian. So do they have collections and do collection management and care? Yes. Do they curate exhibitions? Yes. Do they offer public programs? Yes. Do they organize special events and do marketing and digital engagements? Yes. They make these things happen.

This is Dr. Simge Erdogan-O'Connor, who studies small museums in her academic practice, and works at one.

Simge Erdogan-O'Connor: Hello, my name is Simge Erdogan-O'Connor. I am a museum scholar and professional, currently working as museum manager at a local history museum called the Murney Tower Museum located in Kingston, Canada.

Kingston, Ontario, Canada is a city of about 150,000 people and the Murney Tower Museum is Kingston’s oldest museum.

Simge Erdogan-O'Connor: It will turn 100 years old next year. The museum itself is based in a 19th century military fortification, which was built by the British government as a response to a territorial dispute between England at the time and the United States. And the building itself is called Murney Tower. So the museum, taking its name from that building, but also being based in this building, is very much about that history. Why this building was constructed, what's its relationship to broader Canadian, British, American relationships in the 19th century, but at the same time, the museum is very much about the local history of Kingston as well so we are very local in our focus.

No matter how you define a small museum, Murney Tower is a small museum.

Simge Erdogan-O'Connor: We hold about 1300 objects in our collection and we are seasonal. We are only open to the public from the end of May through September. And I'm the only full time staff member that the museum has, which can also show, I think, many people what small museums are in terms of operational capacity. And then we almost entirely rely on volunteers, interns, and seasonal staff members that we hire in the summer.

Ian Elsner: Right, I was going to make a joke about your, your staff meetings being super quick, but I guess you do have to have meetings nevertheless.

Simge Erdogan-O'Connor: But sometimes I make a joke about that too Ian, meaning, yes, of course, we have board meetings, I constantly have interns, every semester through universities, and in the summer I have three full time staff members. Regardless, sometimes I'm like, I'm the gatekeeper, I am the security guard, I clean the museum, I run the museum, right? I do all of these cool things, like I write the strategic plan, but then there are times that I'm on call waiting for a maintenance person to come to the museum and I just need to be there to open doors to him.

Ian Elsner: I can already see the challenge of having one person do all of those things that you described, but what are some of the other challenges of a small institution or your small institution specifically?