Discover Raised on Rock and Roll Podcast

Raised on Rock and Roll Podcast

Raised on Rock and Roll Podcast

Author: Larry Hicock

Subscribed: 0Played: 0Subscribe

Share

© Larry Hicock

Description

Stories from the days when rock was young – told by musicians from my hometown of Winnipeg (a.k.a. the rock and roll centre of Canada). Based on the book, featuring interview excerpts, out-takes and other delights

larryhicock.substack.com

larryhicock.substack.com

7 Episodes

Reverse

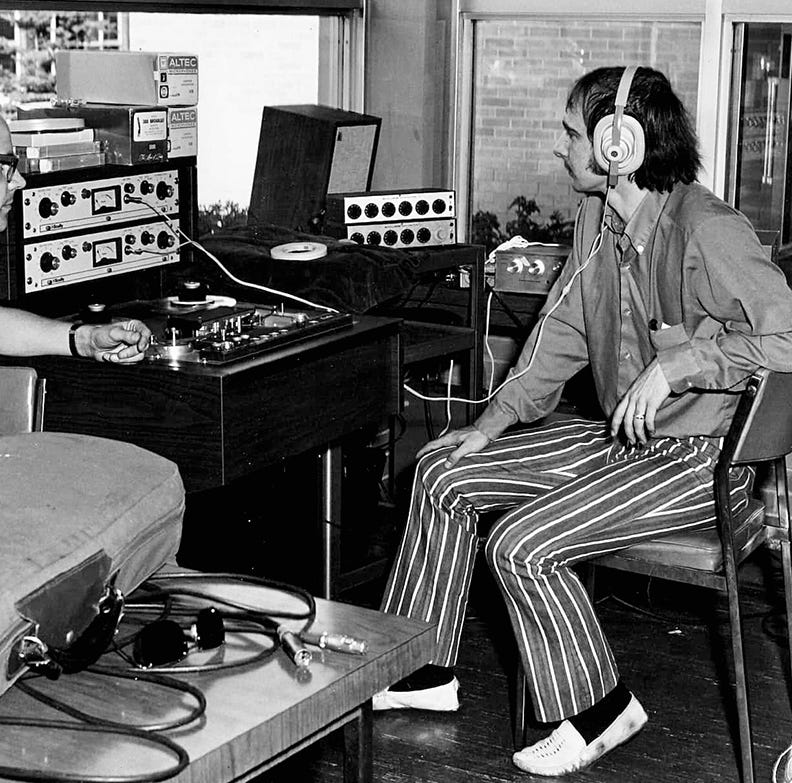

I recently posted a story about the making of Sugar ‘n’ Spice, and Michael Gillespie’s instrumental role (no pun intended) in that band’s remarkable journey. This podcast features the man himself, in his own words.Raised on Rock and Roll – stories from the days when rock was young, and my hometown Winnipeg was the rock and roll centre of Canada…I’m Larry Hicock, author of Raised on Rock and Roll, the book. In today’s podcast, one of Winnipeg’s preeminent behind-the-scenes movers and shakers, Michael Gillespie…Gillespie: I was working at an electronic shop. I was hanging out at this radio station. I was managing the band. And I was designing and building things. My attendance through junior high and high school was spotty, because I was taking university courses at the same time. With some support from a couple of good teachers – they allowed me to do that. So I was actually taking Fortran computer programming at the University of Manitoba when I was in grade nine….Electronics, design and engineering, computer programming (in the early sixties no less). Put all this together and you have the makings of a true super geek, a dyed-in-the-wool propeller head. But then there’s that clue in Michael Gillespie’s remarks that gives lie to the stereotype. What’s this about managing a band?Micheal’s technical and entrepreneurial chops brought him industry-wide acclaim and a thriving international business. The audio components and systems he designed and manufactured are found in the studios and control rooms of broadcasters all over the world. His recording equipment has been used by such major artists as the BeeGees, Fleetwood Mac, Tom Petty, Barbara Streisand, Neil Diamond and countless others.And Michael’s great successes might never have happened without his passion for the music, and the radio stations he heard it on, in the heady days of sixties rock and roll…My mom used to listen to 40s classics, and symphony, and I just became very attracted to music at that time. I got into listening to the radio. As a kid, I would repair old wooden radios, the types of size of small refrigerators. And some of them had a really good sound. So I would recall when blue suede shoes came on, you know, I would crank it up and and enjoy that.But unfortunately, I fall into the same category as every other person I know, that my big epiphany for music was February 1964 on The Ed Sullivan Show. Prior to that I had actually been keen enough and interested enough that I’d been ‘interning’, I’ll say, is a nice way of putting it – at CKY radio. From about the time I was 14. It was in love with the disc jockeys. I was in love with the concept. I became enamoured – I became in lust with broadcasting and music.I would go and spend my time after school in the evenings sitting in the control room at the radio station. I go down in the daytime on weekends, I would go out to remotes that they did – I’d sit in the booth at champs Kentucky Fried Chicken with Darryl Birmingham while he spun records to the drive-in crowd at the place. I would ride in his convertible or Chuck Dan’s convertible out to the sock hops or the dances that they hosted.And that was at age 15. And as enamoured as I was with that, that was going great, it was the Ed Sullivan Show that just changed my my life. Like everybody else – well, not everybody else I know – but the following Monday morning I went to junior high school with my hair combed forward, you know, simply because the Beatles wore their hair forward. And I start getting sent to the principal’s office from that point until I left school, for being ‘out of sorts.’I guess at a certain point during that period, while at university, I became a disc jockey at student radio at U of M. It was not a broadcast, it was actually wired across campus. So it was about as exciting as playing records on the PA system in high school. But I did that too, and did some of my first recording there. So it came from a love of music from my mum, and then just through association with a lot of very influential radio people.I’m not a naturally talented musician. It’s real hard work for me and I personally honestly admit I don’t have the discipline to practice and learn properly, but I fell in love with it. With the first real band I got involved with, watching the other guys in the band, I said well this would be a good way to get a girlfriend. And because I couldn’t play anything else, I decided I could probably play bass. I didn’t know how girls viewed bass players at that point. It was a Hofner bass, an original Hofner bass, Beatle bass, and I got really good. I could pick out the bass lines on the records I heard, but I didn’t have the stamina to play them for the entire length or time with the people that I happened to be around.So – and this is where I did have a major epiphany – I decided I made a better manager than a bass player. And I took over management of the band. My entrepreneurial skills, which I do admit to having, came to the fore, and I booked the band and we played two or three times a week. Neil Young is correct. There were 200 pounds in Winnipeg at that time, we were the Liverpool of Canada. A community club, a Kiwanis hall, a church basement, a hockey rink – we would play anywhere – but we were playing about three times a week. And I managed to get our rate up. I was the salesman, I had to convince them that we were worth the money. We were getting $75 to $80 a night for a five piece band with a manager. And at that time, I remember clearly, I had a separate part time job doing electronic repair. And at that time I was being paid 50 cents an hour. So, put it into perspective of how many days a week did I have to earn to get the 10% I got off of one gig. Seven and a half bucks. Well, that was a long working day. That was two days…That first band, the Griffins, started in 1966. They were still doing well in 1968, but for Michael, things weren’t going well enough. That’s when he had another one of his epiphanies…The one thing that I recognized is that our success and every other band success was our enemy. Because we had so many competitors. We couldn’t raise our rates, we couldn’t get more money because the Mongrels would play for the same rate, or the Other Five would show up, you know, for nothing. It got tough. And that the material, the genre that everyone’s playing was generally the same. So you could go to the same community club every week and hear a different band play, and it was the same music, which wasn’t very creative. And so it was difficult for us to stand out. We’re all long-haired, moustached, sideburns like crazy, we had more sideburns than hair… Wearing tweed British jackets and slacks and Beatle boots, you know – but I mean, if you blinked your eyes, it could be the Mongrels. They looked the same…I said, you know, the music that’s beginning to become very popular is Motown. And there are a lot of female groups coming from there with female harmony, and there isn’t a single band out of our 200 bands that had a female member let alone a female singer or musician. We should find ourselves a really good quality female singer, and we could begin to take on a different genre and be unique amongst the Winnipeg bands.Gillespie put some of the guys from the Griffins together with some new musicians and started a new band. It would have a new carefully designed approach, complete not just with one female singer but three. They called it Sugar and Spice.I wrote a full chapter of my book (plus a Substack feature) on the making of this band and just how close they came to breaking out internationally. It’s a story in itself.For two years Gillespie navigated Sugar and Spice throughout that band’s roller coaster ride. But starting in 1970, his band-managing days would take a back seat.Randy Moffat when he hired me for the job. He says you have two jobs here Michael he says you keep us on the air. Because if we’re not on the air, the 75 people in this building aren’t earning a wage. That was a good point. And he said I want you to make us sound as good as possible. If you can accomplish those two things, your time is your own. You come and go when you want to do what you need to do. You do those two things, you’re doing your job. That gave me the free rein to research. And on CKY’s dime I did a lot of design and fixed, figured out, a lot of things. It was having the opportunity to be there that gave me the ability to research and design a product the way I was trained to design product, and I did it. So I built, installed, designed or renovated 30 AM, FM, TV and recording studios in Canada. That’s my broadcast package.That broadcast package took Michael well beyond Winnipeg, soon enough beyond Canada, and soon after that, beyond the broadcasting industry. The same entrepreneurial chops he’d honed during his rock and roll run would now take him, his products, and his new businesses, into the stratosphere.I’d go into a station and, ‘We need this’ – well, there is no such products by design, we build it. So at a certain point, I end up with a catalog of products that I built special for these places. But now people are phoning me and saying ‘I need one of those things that you put in CKLW,’ or, you know, CKCK or whatever it is. And so I’d be able to sort of piecemeal start to market them. Well, pretty soon I was hiring people to build product so I’d have some when people asked me for them. I wasn’t actually marketing it. So at some point I decided, you know, these things really do have a market. So I went to the NAB show and I showed it to North America’s broadcasters all at once. And it just – straight up – I was doing stuff for everybody.The product I was building to make things sound good on the air – known generally in my terms as audio processors – limiters, compressors, expanders, equalizers, that kind of gear.I had taken everything I learned and I built it into a single product, and I took that to NABA, the natio

From the North End With Love. And Brass Knuckles. And 4-part Harmonies.Raised on Rock and Roll, stories from the days when rock was young – and my hometown Winnipeg was the rock and roll capital of Canada….I used to try and force myself – I was working at a day job, too – but I'd come home and I used to try and write four or five songs every day. Just for practice. I was trying to teach myself phrasing and whatnot. I didn't have anybody showing me – like how can you? How could I show you how to write a song – you can't, it's got to come from your own head. So I would just do that, and every once in a while I’d come up with something that I liked..So anyway, I had this whole big pile of songs, and I’d put them in a briefcase and I used to go around to there were different groups, like the Jury, that were playing around in the city, like the Jury, and I’d sit down with my guitar and I’d play them song after song after song and see if there was anything they liked. And the last one I sang for the Jury was WhoDat, so they recorded it. So yeah, that worked out okay.And then Donnie McDougall, him and I wrote a few tunes one morning, and he ended up going to Vancouver and joining up with a group called Mother Tucker’s Yellow Duck. They were a big band on the west coast. And so they recorded a couple of my songs – Donnie and I wrote two of the songs, yeah.Singer, songwriter Bill Iveniuk is a product of the times – in his case, coming of age in the mid-1950s. And he’s a product of his environment. He was born in Point Douglas, a working class neighbourhood right next to Winnipeg’s infamous North End and just as tough. He was raised alongside his seven siblings. His father, known by most as Big Jim, was a tradesman, a mechanic, a some-time fur trapper. Back in the day, an amateur boxer. He did a little time for punching out a cop. As you might imagine, Big Jim was a big influence on young Bill.It was like the Bowery boys or something that, you know, we were kids, we did a little stealing, like in gardens and that, like cucumbers and stuff, bring them home for our parents. Like, my dad was a labourer, so I mean he wasn't making a whole lot of money. So he would do his regular job at the city, and then he would fix cars. And so we'd be working, you know, like with my dad, like working on cars and stuff like that, you know, he’d say, you know, pass the half-inch socket, and you’d be daydreaming – like you’re a kid, right? And so what he used to do is, he used to get the metal part of the hammer in his hand and whack you in the forehead with the handle. Wham! Wake up, y’a*****e. Like, I had a lot of welts on my head. And my old man was the kind of guy like – he didn't have time to argue with you, ‘cause there's eight kids and they’re all running around, bouncing off the walls and what-not. So it was, you do this or else it was wham, right? But there was no problem. We had a great childhood, right? Like I didn’t see anything wrong with it…When I was about, maybe eight or nine, I got a paper route. Like 75 papers, I was doing the whole neighbourhood with the paper route, in the winter – you know what the winters are like in Winnipeg – and so winter and summer and all that. Then I got a job in the bowling alley setting pins. And a lot of the guys – you had to set pins, you had to sit in the back and set the pins physically, there was no automatic stuff there – and there was a few of the guys who didn't have any front teeth, like from the pins, taking them out, right? Whang, there goes your teeth, right? And sometimes you'd be in the pit, and some arsehole would throw a ball down while you were in there, you know, showing off to his girlfriend or something? So we used to take the ball and come out from behind the screen and whip it overhand back at the arseholes, right?And yeah, you’d have all these different kinds of jobs. I got a job in a factory that was making mattresses right. And so I was working away – the first day, right? I was about two hours into the job – and one of the bosses comes up to me and he says, you know how to run a forklift? And I thought I should know, right? I should know how to operate a forklift. I guess I was about 14. He said I want you to get a load of these springs and bring them back to these tables. So I said ok I’ll go get ‘em. On the forklift, the big pedal is the gas and the little pedal is the brake. And I got confused when I was driving. I got ’er going, right, and like somebody came across from a different way, right, like an intersection kind of thing? And I went to step on the brake and I goosed this forklift and went full speed into a pile of springs, and smashed all these springs. So I guess I was on the job for about two and a half, three hours and got fired. And that afternoon, I got another job in a pickle factory. So it was like, you could get a job just like that. And so I had those kinds of jobs.Still in school, these are just summer jobs. And then I got a job – my dad got me on at Burns – remember Burns? And the job was like making brine for the hams. What you had to do, you go into this room, and it would be full of salt. And you'd be in there, you'd be shovelling the salt into this big vat on the other side of the wall. You’d have to do that all day…When Bill and his best buddies started junior high over in the North End, they found themselves in a whole other world. And it wasn’t because of their new schoolSo we were gong to Aberdeen School, and there was a restaurant just around the corner on Selkirk Avenue called Nancy’s. And Nancy's was the hangout, like one of those Happy Days restaurants, you know, 10-cent milkshakes and all that – and all kinds of lunatics, you know, hanging out in the place.Like the north end, like on a weekend, like on a Friday night or something, could swell to like almost double the population, because the motorcycle gangs from Transcona would come to Nancy’s – riding their motorcycles up Selkirk, with their arms folded, like no hands, and going like 60 miles an hour, you know, coming up the street, right? Just like in The Wild One, like Marlon Brando, you know, they would emulate those, you know, like what they see in the movies, right. And, you know, with the cigars. And then they’d stand around and some of them would be pushing weights and acting tough and and whatnot. And then, Hey Bill, want to go for a ride on the motorcycle? You jump on the back and you’re going like 80 miles an hour down Selkirk. I’d never been on a motorcycle before, right? And I was like, Oh my God, I mean, I’m gonna die, right? But yeah, and so I mean – but everybody, like once in a blue moon there'd be a gang war, like with chains and all that stuff, right? But that was just, that was rare, that never happened that often. I mean, it was usually one-on-one or a fight in the canteen. Or, you know, and it was usually like one hit – that would usually stop the other guy, right?It’s pretty cool to be on the good side of the bikers, but there was another crowd hanging out at Nancy’s too. Bill Iveniuk and company fit right in with this one.A cappella vocal groups – groups sort of like the Four Lads but maybe before that; the Diamonds, sha-boom sha-boom, like those songs – and so in Winnipeg, groups were forming and they would sing those songs. And the odd group would write some with their own material, very little of that, but there was all… – like there must have been 35 groups in Winnipeg at the time, really good groups…There was a group called the Angels. They were probably one of the best groups in Winnipeg, and the lead singer of that group was called Walter Teske. And Walter Teske, he was sort of like, he was a teacher. he would get the young kids – like he was maybe two or three years older than us – and he would teach us. He would say ok, you sing this part, and he would teach you that part, and you, Bill, you sing this part, and Kody, you sing this part – and so the three or four of us would go and we’d get this harmony – and it was like, wow, we didn't know we could do this. Right. And he would just constantly be teaching us. And then he would go and do his own thing with his own group, right.And so he called me up one time and he said, Bill he says, I'm going to come over with a few beers. And he says I got a guitar here for ya. He says, like, it’s about time you learned guitar, right. So my dad was sitting at the dining room table, looking out the window into the lane, and here comes Walter Teske with a garbage bag, a double garbage bag. I have 70 beers in the garbage bag. Well, my old man liked to drink, right? So he ‘C’mon in Walter’– quack quack quack.… So we go downstairs, we're going he's teaching me all day if I didn't have a pic to use the paper from a match book, and you know if we're playing guitar and teaching the chords…He was the key for me, to have an interest. like, it's like, once you start once you start playing an instrument, you started seeing the possibilities that could open other doors for you, right? – with girls, and or to make a few bucks, right? So that's, like Walter Teske was a huge important part, you know, like in my life.I was a kid, right, and he was an older guy, right? And he wasn't hanging out with me. He was just, he just liked me. He liked the way I sang, he liked my attitude. He liked my family, like, you know, my dad, and the friends that I was hanging around with. It was just that it was a community right, it was like – there was no television. You know, there was like, no video games, nothing, so people – how were they spending their time, right, like what were they doing? They were outside. They were interacting. There was community.When I was 17, I wasn't doing well in high school. I didn't give a s**t, right. And so my dad sat me down, my mom was there, and my dad sat me down and said, ‘Okay, you've got three choices. One, you can join the army. Two, you can take a trade. And three, you can get the hell out of the house. O

Raised on Rock and Roll – stories from the days when rock was young, and my hometown Winnipeg was the rock and roll centre of Canada.Marty Kramer: I was the kind of guy that my parents were old school and they said, Oh, guess what? We've got an instrument for you. We're going to give you lessons – violin. Great. So I said look, Dad, I don't want to play the violin. He said you're gonna play the violin. In those days, you never bought the violin. We rented it. I used to go for lessons at a music store on MacPhilips and Aberdeen or something, in a building. I go there, I hated it. He dropped me off. And then he'd go away and an hour later he comes back. Well, I knew if I didn't go in, I'd be in big trouble. So I went in, I'd sit there, your teacher was very good. They show you how to resin the bow and hold it under your chin and start he and all this and that wasn't for me. I think I lasted… one for sure. maximum two lessons. That was it. No more violin. Then I watched these guys playing guitar. I watched these guys playing drums. And of course, they're honing their skills. I wasn't really looking for, nor were they looking for, somebody to join their band. They were looking for somebody to get them sort of exposed and get out there making money.Meet Marty Kramer – ex-violinist and soon to be go-to band manager, tour manager, artist manager – for anybody who’s anybody, or wants to be.One thing led to the other, I started talking to guys who were in bands or wanted to be in bands. And I said, Well, look, maybe I can get you into our school. I talked to the social committee, this that, next thing I know, I'm the guy that sort of placing the bands in a two or three mile radius at the schools and everything. Then I found out that the churches had halls and that they could provide the same type of thing. So when you could offer an agenda to the school guys – that on a Friday they could strut their stuff, on a Saturday, maybe even a Sunday afternoon in the park or something – you ended up getting all these phone calls. And hey, what's what.. and I can remember working bands for $5, the band playing for five hours, me getting 10% of $5, which was 50 cents. Now 50 cents in those days when you got $1 on the weekend allowance from your parents 50 cents was good. You were making money.So if I worked Friday and Saturday, being around hanging around with these guys doing their thing with them, not playing musical instruments or anything just being there, guess what? I was the big shot. I was the go-to guy, Marty'll do this, Marty'll do that for you. He'll get you a booking. So it unfolded. Before I knew it. I had a small roster of guys that were musicians, I was going to their house for rehearsing and this and that, and you ended up getting a commission. I also had a driver's license, which a lot of these guys didn't. I also had an uncle who owned a rental company in Winnipeg. So thus I could rent a van. This was big, because you'd have to put all your stuff in cars or in trunks of cars and station wagons, and trailers. Well, when I showed up with a panel truck, and we could load everything in there, wow, and I could drive. And two of them could sit with me because they had a bench seat. And the others could go with a father or a parent and drive them to the gig. This was the do-all be-all in those days. And thus, I met my very first encounter with anybody that I thought could cut it, was Burton Cummings.As I said earlier, five bucks for a band was a lot of money. With my commission – my commission of 50 cents – after the show we used to go and I could buy a hotdog, chips, a drink, one bubble gum and two licorice, one red, one black, for 50 cents. And that's the God's truth. Now, on a good night, on a good night, Burton Cummings would say – when we were getting our food at the drive-in restaurant – he would order gravy on his fries. That was five cents extra. Well I didn't have that five cents. Remember, it was five bucks. I took 50 cents. There was five guys. Each one of those guys got 90 cents. So they were ahead of me by 40 cents. On a good night, Burton would say – he’d spent 55, he’d say ‘Put gravy on Kramer’s fries too and I'll pay for it. So he ended up paying 60 cents out of his 90 and I ended up getting a gravy on my fries.So that was my first introduction. And then, from that point on, I just stuck with Burton. The Deverons evolved. I became the manager of the Deverons. I did the Deverons for as long as it stayed in existence, and then with Burton leaving the Deverons to go to the Guess Who, then I was introduced to a different ballgame with Randy Bachman. Garry Peterson, Jim Kale, Bob Ashley – the original guys minus Chad Allan. So Chad took a backseat, Burton stepped in, and from then on, it's been a ride of a lifetime. 27 years with Burton 27, 20 years with Randy.Even before going into the business full-time, Marty was working with Winnipeg’s top booking agents – as a go-fer, chauffeur, or part of the show crew – for virtually every major artist passing through town. From Liberace to Led Zeppelin, from Roy Orbison to the Monkees. Fats Domino to the Rolling Stones. For a lot of these events, he made little or no money. He loved the music, he loved the people, he loved the action. By the time he moved to Vancouver in 1979 – still working with Burton Cummings, now at the height of his solo career – Marty knew everybody – artists and their managers, booking agents, promoters across North America. And more important, everybody knew him. He was still the go-to guy and he knew each and every facet of the trade.Here's what I do on any given day – as a tour, band, artist, manager – any of those hats, or all of those hats. So, here's what I do. Contact the artists, the band, once a show or tour is confirmed. That's number one. Number two, hire the band and determine the salaries and the per diems for everybody – salaries meaning what they get paid, per diems meaning cost of living each day for food allowances and so on. Compile the tour budget, which includes all costs, which includes me, sound, lights, buses, transportation, airfare, rooms, you name it. Compile song lists for each performer in the band – with, usually, the lead singer, in this case, Burton. Okay. Confirm a rehearsal date, time and place – because you have to rehearse when you’re going out – I’m talking of touring. Then, establish length of sets and running order of the performance. If there's multiple people on, if you're the headliner, which means you go on last, everybody that precedes you are opening acts. Book airfare, hotels, as well as rental vehicles, book rental gear, sound lights, instruments and technicians. Because we don't usually like to have to bring everything with us and schlep it across the countryside, predominantly. We would bring in the old days – Burton’s piano of course for that sound. The guys would bring their guitars, Garry would bring his drums, but for the most part, all the other amps and necessities, we booked them.Make up set lists and tour itineraries for everybody and distribute them, so they know what they're doing. Transport performers to and from the rehearsals in the venues, which was me, I never let anybody else – I never let that band out of my sight. Nobody touched them. If somebody else picked him up and I didn't drive them, I was sitting in the passenger seat and the band was in the back.Advance all the shows, with stage props, technical riders and showtimes, which means, I need to know the lighting configuration, I need to know how much power I need. I need to know how many men I have to come in. I need to know all the showtimes. I do all that. Then once we're on the road, contact all the venues we're playing at, and the hotels, to confirm everything. Compile rooming lists and distribute them, and the per diems. Once we're at the venue, assign the dressing rooms, see about the catering, staffing, conduct the soundcheck, which me ans you do a sound check with all your stuff. So there's a line check, which is just the instruments minus the artistry. Soundcheck is full-blown sound, everything is going, making sure it all works. Deal with the press media, guest lists such as yourself, merchandise, who’s coming – radio DJs, interviewers, guys writing books, guys wanting to take pictures, we got to sell shirts, got to do all that. Show time, till the end of show time, I'm in charge, and always there for the performers, band and techs. I'm always there. After the show a meet and greet, which is you, backstage passes, whatever, with performers, and sell merchandise. Then, tear down, take everybody back to the hotel, and do it again the next day. And at the end of the tour, pay everybody, fly or drive everybody home until the next time, and that is what Kramer does. On a daily basis. Every day.– Okay. There’s only one thing I’m not hearing here: It was a ball, or, it was a living nightmare…It was a living hell, because you never knew what you're up against. Whether it's the elements, whether it's weather, whether it's airport delays, whether it's vehicle breakdowns. The worst thing that can happen, of course, is accident and sickness. If you're on the road, it’s not like COVID where you get taken right out. But if you've got a flu… And fortunately, I can honestly say that in all the years that I worked with Burton – as the Deverons, as the Guess Who, as Burton Cummings – I only had two cancellations because he lost his voice. With the Guess Who reunion tour, we only had one because he lost his voice. And that's it. So that's pretty damn good. And everybody else – I’ve had all sorts of things happen. But like you say, it's not, oh, here's comes that guy, open the door for him. He's got that plush office, sit down, wine, women and song – you have to have your wits about you. If you're fucked up, excuse the language, and you're bent, this ain't gonna happen. It's gonna be a s**t show. I have a meticulous record, I have a fl

Raised on Rock and Roll, stories from the days when rock was young. In this episode, four little stories from what was being called the folk revival of the nineteen sixties.Len UdowI had a group called the Wayward Four…– Perfect name.I played guitar. And we had three other singers. And some guy joined us later and played banjo. And we were doing a kind of a Brothers Four kind of a – you know, or Kingston Trio. Anyway, we ended up on a TV show called The Talent show, I think, the CKY Talent Show. And this was early 60s. And we won. Like we were the champions for that year. And we were asked what we would like for a prize, and we all elected to get curling sweaters…Bobby Stahr– When did you start, or did you start, to think of music as your career?It’s never been a career, it’s a lifestyle. Right from start. Once I started playing guitar I knew I’d be doing that in my life forever. There was never any doubt about it. But it was never a career. It was just what I did with my life. I’ve already played guitar for an hour, hour and a half, earlier today… – A lifestyle choice. What does that mean? Tell me what that means to you. Well, if I can't bring my guitar, I don't want to be there…. How’s that.– That’s perfect.Like my guitar is part of me. If I want to take it, I will. And if you don’t want me to take it, I won’t go.Rick Neufeld. I'd been writing songs and songwriting was still – you know, ‘singer songwriter’ in the early 60s was still a bit of a novelty. And I never was a great guitar player, or singer for that matter. But people like Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen proved to me that you didn't necessarily have to be if you could write a song…In my hometown, some of the rockers ,like Winnipeg’s own favourite son Neil Young, were exploring acoustic folk music.. And some of the folkies (under Bob Dylan’s shocking turnaround) were going electric. If you were just discovering it, Winnipeg was a pretty great place to experience it. No matter which camp, or which part of the city – or in Rick Neufeld’s case, which part of the countryside, you came from…Rick Neufeld My Uncle Henry played the guitar and, and his sister, my aunt, sang with him. And they would sing in church. And, and yet it wasn't, they weren't singing hymns. They were singing sort of less churchy songs. And that caught my attention, although I did always enjoyed singing in the in the choirs. But that got me interested in wanting a guitar and somehow I got a guitar and then learned how to play it to some extent. And then when I got to the University of Manitoba, studying architecture, I started playing in coffee houses and you know, church basements, the Home Street United Church basement…I did not enjoy being driving that tractor all day. I mean, I screwed up so bad. I would get to the end of a field and I'd be daydreaming so much about being on second base against the New York Yankees or, or whatever my my fascination was at the time, I would go through fences, I would tear up hydraulic hoses. I was a terrible, terrible slave on that farm as an eight, nine year old boy. And all I ever wanted to do was go, and get out there in the world and my uncle Henry's guitar. I don't know, I just saw that as a, as a signal that that's that's something I would do.And back then in the coffee house scene, I remember Mr. Bojangles and Little Bird Come Sit Upon My Windowsill, Jerry Jeff Walker songs that I would do. Eve Of Destruction was one of the first songs I remember doing. And then mixing my own songs in.…I must have just written Moody Manitoba Morning. Because it was after I got back from that trip to Europe trip. And before I headed back to Montreal to work in a record store there and basically where my publisher lived, and he just wanted me in the proximity and, and get me to good writing habits, working habits because in Manitoba, it seemed I was a little bit too sociable in that scene.In Europe Rick befriended another Canadian traveller. They travelled together till they ran out of money and headed back to Canada.His name was Richard Hahn. And he said his father was in the music business primarily as a jingle writer. He wrote off he wrote all those like Dominion, “it’s mainly because of the meat”, and DuMaurier, “for real smoking pleasure”, “drive in at the sign of the big BA” – like all those hits from back in our era, on the radio, advertising. And he was getting into music, into producing music. He was tired of the jingle business. And so when we got back to Canada – we barely made it to to Montreal with what we had left. – after getting a flight from Scotland in Newfoundland and getting from Newfoundland to to Montreal – and I played Bob some of my songs, and he was from Saskatchewan.And he was so enthusiastic about my simple little songs, because he related to them. And I went back to Winnipeg. And when I got back, there was a letter from him saying, you know, I'm going to be producing this album by a band called The Bells. If you can write something we'll get them to record it. And so I wrote Moody Manitoba Morning and sent it to him… And the Bells somehow as a B-side had a lot of radio performances out of it at a time when Canadian music was being promoted, to be played. And I'm not crazy about the version they did, but hey, it was it was a hit. So suddenly, I was a songwriter, an actual songwriter. And that was the beginning of that…Len Udow I'm one of the lucky people. According to one of my neighbours, he was a neighbour and he came up to me said, you know, you're one of the few people that actually made a living, or survived, being a folk musician. But I never thought of myself as a folk musician. I just sort of seeped like water into all these different crevices, you know. I mean, I was trying to be more mercurial than anything, because I knew I had music in me, but I had to try different things, and see where I could fit in.For singer-songwriter Len Udow, trying different things came naturally. It’s what he grew up with…I think I had a pretty complicated childhood, musically, because my mother and my aunt and my uncle were supreme beings, musically. Opera, as well as the American standards – so there was a bit of jazz, there was a bit of folk, and there was a bit of what’s called Yiddish. And my mother sang opera with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. And as a child, I went to rehearsals, and I was fascinated with the kettle drums and, and seeing this room full of fabulous music. So I don't remember a light ever going on, because I don't think light ever went off. I think I was surrounded by such passion and dedication and commitment. And it was the daily expression in our home.Because I mean, look, opera is in itself, it's a European culture, it’s a folk culture, that entered my parents lives along with the American Songbook. What was entering into my life was Odetta, Leon Bibb, Pete Seeger. My mother was buying their records. I was hearing the you know, the Kingston Trio. I remember being fascinated with Greenback Dollar, it was a tune that they did. ‘Some people say I’m a… Others say I'm no good.’ And of course, I'm playing guitar at this point – that my father bought me. My father bought me a guitar from Eaton’s. It was a plywood thing. It had a lady doing a hula, and a little pond, and a tree, a palm tree, and it was awful. The action on it was so bad. And I played with my thumb, I didn't have a pic. And I would bleed, and my hand would be so sore. And… ‘Some people say I’m a… – and I’m into this… I used to do the Ox Driver Song, which came from Australia, with that thing… Anyway… And eventually he bought me my Martin guitar, that I still have today.Sometime around 1963, Len brought his beloved Martin with him to the city’s hippest coffee house. It was called the Fourth Dimension.It was an old nightclub that my grandparents used to go to with a bottle of wine under the table, during Prohibition, and it became a folk club. and you were charged 25 cents an hour to sit and maybe you order a coffee, and catch the the whatever, whatever the the main, the main act was, usually, it was part of a circuit that was Thunder Bay. Winnipeg and Regina. It was a black box. Black. Black walls, black floor, black furniture. And it had a little stage with very minimal lighting. It had a nice sound system, I think. And it had an espresso machine. And they made, I don't know, some kind of primitive food, I guess. So I would go in, and I would be one of those patrons, I guess, when I first began. But I never expected that I would play there, until I realized that anyone could play there on a Sunday. So I guess I was talked into going with my guitar by someone who was already going in, and I performed, and then I sort of got a toehold that way. At the Four D, and then I started being asked into the back room, where you could go and play and be with some of the traveling musicians that came through.These were exciting and inspiring times – meeting all these musicians, hearing their music – and so was the 4D itself. It was way across the city from Len’s West Kildonan neighbourhood. That was part of its attraction.West Kildonan had its own city hall, its own mayor, its own police force. So did St. Boniface, so did St. James. So until it was amalgamated into one city, it was really a city of separateness, you know, separate parts. I was at that point in which it was starting to become amalgamated. Like when I was young, like 13,14, I remember getting on my bicycle and going outside of West Kildonan. Wow.You know, that was unusual, like to actually go to East Kildonan. So that interested me. And folk music, I felt, was the expression anyway, of what it meant to be a human on the planet. And that from our separate cultures came somehow an understanding of how it could work together. And so the Four D was almost like the pinnacle of that. And it wasn’t just a dating game. It was a life passage, that you had to go through in order to enter into this huge amalgamation o

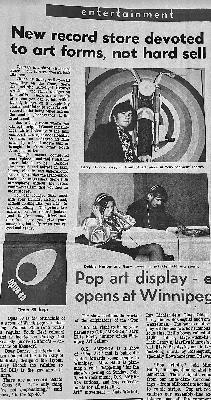

Raised on Rock and Roll – stories from the days when rock was young…In late-1960s Winnipeg, there was a record store that wanted to be a cultural hub. And for a while there, it was. I’m Larry Hicock and this is the story of the making of Opus 69.Norman: It was actually a wonderful experience, a very intimate group, and it was very personal. We had about 50 regulars, but with no money, and I knew all their names, and I went out with two of the girls who were vocalists that were there…Norman Stein launched Opus 69 in… 1969. Before that he’d started a company called Campus Records Distributors, selling records to university bookstores across Canada. Before that he was a teacher – kindergarten to high school. While he was doing that, he was also writing reviews and articles about classical music, ballet, theatre, film, opera. Then he started writing liner notes for RCA Victor’s new classical releases. He shared some of these records with his students – but they weren’t the classical stuff.NS: I had the entire RCA catalog at my disposal in pop music and in rock. They would send me a whole bunch of classical and rock, starting to start rock music, for me to analyze. And they would send me all these LPs that haven’t been on the market yet. In the high school where I taught, I started a rock group, of rock rock and roll. So the kids would vote on what they thought would be successful.Norman’s rock and roll club was a hit with his students. So was his work with the big classical labels – RCA, Columbia, Deutsche Gramophone. By 1961, he’s hobnobbing with the likes of Leonard Bernstein, for whom he’d co-host the New York Symphony Orchestra’s first appearance in Winnipeg. Ne met Leonard Bernstein after a concert in Vancouver in 1959. Bernstein was impressed with Norman.NS: I had some ideas on music I wanted to test for Leonard Bernstein in 1961. So subtract 1932 from 1961 to get an idea how old I was. And he was quite interested in my research with youth, and how to identify members of the orchestra, the different symbols of the orchestra. And I used to get the sound effects records and I taught kindergarten age children how to recognize a viola from a violin, a bassoon and oboe and all that.When somebody like Norman opens a record store – someone bright, well-versed artistically, and maybe a little bit quirky – you just know it’s going to be different.Starting with his young students and for decades to follow, Norman turned a lot of people on to a lot of music that they might not have heard otherwise. I know because I was one of those people. Records you couldn’t find anywhere else, and that you certainly weren’t going to hear on Top 40 radio. That’s what Opus 69 was all about, and it was kind’ve Norman Stein’s mission in life. I know this about Norman too, because I got to know him a few months before Opus. And when he opened the store, the guy he hired to be its first manager was me.*Opus 69 was located right downtown, just off Portage Avenue on the second floor of the very prim and proper Clifford’s Ladies Wear. When people asked Norman how he came up with the name Opus 69, he’d smile and tell them “because it’s 69 steps off Portage.” Nudge nudge. Wink wink. He delighted in these little quips. If someone offered him a cigarette, he’d say no thanks, I don’t smoke… tobacco.The store wasn’t big but it felt big. And modern. And cool. Everything in it was designed by a fourth-year Interior Design student named Doug Barry, including the custom-built furniture and fixtures, right down to the logo – and he won a design award for his efforts.The store had thick purple wall-to-wall carpeting, which also ran up to the top of the sales counter. It had sleek white record bins. It had listening rooms – a first for the city. You could sit back in a big comfy chair, put on a pair of big headphones, and someone at the counter would put on an album for you. You could listen to a whole side; if it wasn’t busy, maybe both sides. If the listening rooms were taken, someone behind the counter would cue up your request and blast the hell out of it over the magnificent sound system.Of course you could buy the record, but nobody pressured you. This itself was part of the store’s appeal, and why it quickly became a popular hangout. But as great as the vibe was, it was the records, the incredible selection of records, that set it apart. And not just for the rockers.Opus carried an eclectic inventory, including rare and exclusive imports – blues and folk music on obscure American labels from the 40s and 50s. Classical and avant garde and electronic and jazz albums from Europe and Japan. The shop carried virtually everything except Top Forty. That was always Norman Stein’s intention.Opus 69 was going to be different. Norman wanted to make a statement to that effect literally from day one. So he put together a truly grand grand opening – a week-long mini-festival of the arts, featuring live music, poetry, an art exhibit. Among its contributors was this techno-wizard guy that everybody called Stytch; he brought in his experimental art film…Jim Stoyka: This voluptuous young lady agreed to do nude scenes with me, which kind of blew us away, but anyway, it worked out quite well. However, we found that she didn't look as sexy when she was nude than if she had her jeans on. And so what we did was, I sat cross-legged talking a blue streak. And then she came in, stage left, cracked an egg over my head, and then left stage right. And that was the opening credits of the film. Then it all went from there.Making films is just one of Stytch’s many talents. His real forte is electronics. By the time he’s 16, Stytch and his buddy Richard are rummaging through the city dump, pulling apart old TV sets for their parts. Next thing you know, they’re running Winnipeg’s first – maybe Canada’s first – underground radio station.JS: Yeah it was a basement radio station. Richard lived a couple blocks away. And he offered to have it at his place, because he had all the records. He had about 400 45s at the time. I guess we got together and started talking about putting together a radio station, because he had all these records and they weren't playing rock on the radio stations at that time, certainly not continuously.– Did you know who was listening to you? Or did you have a sense of who you were connecting with?Yes, because we gave out the telephone number and we had dedications. Once we were on the air, the family whose phone it was, they couldn't use the phone. It was rock solid. We were at the point where you could just hang up and then just pick it up again and say hello. And there's somebody there…– This is pirate radio. Pirate radio… How long did you man the station so to speak…Our hours were six o'clock till six till 10 or 11 – 10 every day except for the weekends, and on the weekends we went to midnight. And we did that every day. And every week. Once we started, we were on the air continuously, except when we saw a Department of Communications truck with all its antennas in the area, we shut down.Jim Stoyka – Stytch, that is – came to Opus initially to set up the store’s audio system, including for the grand opening. With Stytch, Norman got more than he bargained for, and he loved it.NS: I rented the place from Clifford’s Ladies Wear. There was a joint toilet between his staff, downstairs and mine. And my – I don't know what you would call him, a techno-engineer, to be more or less in the vein of Zappa and some others. He said, You know, there's a window there that goes into that small room. But we'll have to take the toilet out because I have to manipulate that.JS: That became the projection room and there was this, we put a sound rack in there, a 19-inch sound rack. And a sound system. It was a 20 seat theatre as I recall. And so it wasn't very big. But all the headphones came back to a jack panel and I could patch in whatever soundtrack I wanted to each individual headphone.So, everyone would take their seat and as the lights went down they’d be asked to put on their headphones. This is where the projectors kicked in. Older listeners might recall seeing one of those things in the classroom or maybe in a business meeting. You’d take your material – a map, a diagram, a business report – and project it onto a big white screen so you could present it to your audience. In the mid-60s, these same projectors started showing up at rock concerts – psychedelic rock concerts. You’d put some water in a curved glass dish, add in a few drops of different coloured oils, and then you’d slide the dish so the colours moved around and blended together, preferably in time with the music, and that would be projected onto a screen behind the band. If you were there, and if you were zonked out on acid or something, what you got was a light show – a mind-bending experience as it were… That’s exactly what our man Stytch was going for. Not with a band, in this case, but for his film.JS: We presented the film on the first day, and it went over like a lead brick. It was called Nowhere Man. I was the lead actor, and it was about, we decided to give them what every – what we thought everybody thought hippies were all about. And, you know, so I was a dope-smoking hippie, and then I’d go to this girl’s place and I’d undress her – and nothing happened. I just undid her buttons – thirty buttons on this stupid thing and I couldn't get them undone. And so that's what made the movie very boring. But I'm very realistic. It is. But to spice it up. We decided, okay, well let's bring in the light projectors. And let's mask the film with the light projectors. So we did. And once we did that, well, this became a very hot, sexy sort of thing, because nobody could see what was going on. You know, as I said, little excerpts of this hippie guy trying to undress this woman. And it worked it, it changed the whole feel of the film.NS: He removed the toilet – it’s a good thing he didn't throw it in the garbage –

Get full access to Raised on Rock and Roll at larryhicock.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome to the first episode! The series begins, like the book does, with some of the youngest musicians and most popular bands in the early- to mid-sixties. After working for some three years just with transcript print-outs from my interviews, it’s been a real joy for me to actually hear these guys again (and later some girls too). In this and future episodes, I’ll include direct quotes from the book along with some “outtakes” and commentary that complement the book’s stories. Special thanks for their contributions: To Ron Paley and Bev Masters for providing tunes by the Eternals, the Crescendos, and the Fifth. And to Gord Osland and Steve Hegyi for permission to use adopt their tune, Wanna Go Rockin, for the series theme. (You can check out more of their music at giantsheadmusic.com.) Get full access to Raised on Rock and Roll at larryhicock.substack.com/subscribe