The Making of Opus 69

Description

Raised on Rock and Roll – stories from the days when rock was young…

In late-1960s Winnipeg, there was a record store that wanted to be a cultural hub. And for a while there, it was. I’m Larry Hicock and this is the story of the making of Opus 69.

Norman: It was actually a wonderful experience, a very intimate group, and it was very personal. We had about 50 regulars, but with no money, and I knew all their names, and I went out with two of the girls who were vocalists that were there…

Norman Stein launched Opus 69 in… 1969. Before that he’d started a company called Campus Records Distributors, selling records to university bookstores across Canada. Before that he was a teacher – kindergarten to high school. While he was doing that, he was also writing reviews and articles about classical music, ballet, theatre, film, opera. Then he started writing liner notes for RCA Victor’s new classical releases. He shared some of these records with his students – but they weren’t the classical stuff.

NS: I had the entire RCA catalog at my disposal in pop music and in rock. They would send me a whole bunch of classical and rock, starting to start rock music, for me to analyze. And they would send me all these LPs that haven’t been on the market yet. In the high school where I taught, I started a rock group, of rock rock and roll. So the kids would vote on what they thought would be successful.

Norman’s rock and roll club was a hit with his students. So was his work with the big classical labels – RCA, Columbia, Deutsche Gramophone. By 1961, he’s hobnobbing with the likes of Leonard Bernstein, for whom he’d co-host the New York Symphony Orchestra’s first appearance in Winnipeg. Ne met Leonard Bernstein after a concert in Vancouver in 1959. Bernstein was impressed with Norman.

NS: I had some ideas on music I wanted to test for Leonard Bernstein in 1961. So subtract 1932 from 1961 to get an idea how old I was. And he was quite interested in my research with youth, and how to identify members of the orchestra, the different symbols of the orchestra. And I used to get the sound effects records and I taught kindergarten age children how to recognize a viola from a violin, a bassoon and oboe and all that.

When somebody like Norman opens a record store – someone bright, well-versed artistically, and maybe a little bit quirky – you just know it’s going to be different.

Starting with his young students and for decades to follow, Norman turned a lot of people on to a lot of music that they might not have heard otherwise. I know because I was one of those people. Records you couldn’t find anywhere else, and that you certainly weren’t going to hear on Top 40 radio. That’s what Opus 69 was all about, and it was kind’ve Norman Stein’s mission in life. I know this about Norman too, because I got to know him a few months before Opus. And when he opened the store, the guy he hired to be its first manager was me.

*

Opus 69 was located right downtown, just off Portage Avenue on the second floor of the very prim and proper Clifford’s Ladies Wear. When people asked Norman how he came up with the name Opus 69, he’d smile and tell them “because it’s 69 steps off Portage.” Nudge nudge. Wink wink. He delighted in these little quips. If someone offered him a cigarette, he’d say no thanks, I don’t smoke… tobacco.

The store wasn’t big but it felt big. And modern. And cool. Everything in it was designed by a fourth-year Interior Design student named Doug Barry, including the custom-built furniture and fixtures, right down to the logo – and he won a design award for his efforts.

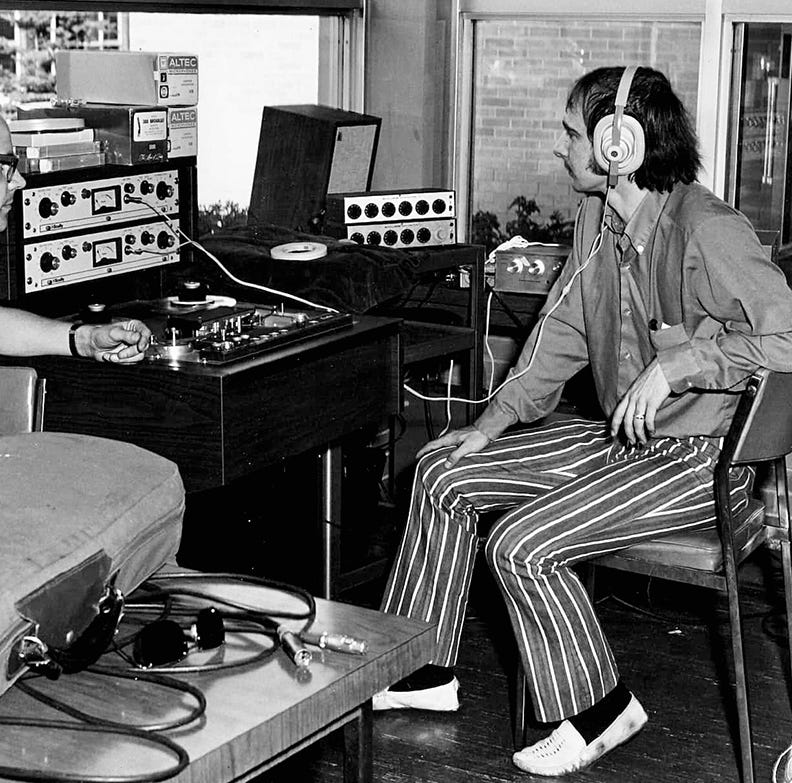

The store had thick purple wall-to-wall carpeting, which also ran up to the top of the sales counter. It had sleek white record bins. It had listening rooms – a first for the city. You could sit back in a big comfy chair, put on a pair of big headphones, and someone at the counter would put on an album for you. You could listen to a whole side; if it wasn’t busy, maybe both sides. If the listening rooms were taken, someone behind the counter would cue up your request and blast the hell out of it over the magnificent sound system.

Of course you could buy the record, but nobody pressured you. This itself was part of the store’s appeal, and why it quickly became a popular hangout. But as great as the vibe was, it was the records, the incredible selection of records, that set it apart. And not just for the rockers.

Opus carried an eclectic inventory, including rare and exclusive imports – blues and folk music on obscure American labels from the 40s and 50s. Classical and avant garde and electronic and jazz albums from Europe and Japan. The shop carried virtually everything except Top Forty. That was always Norman Stein’s intention.

Opus 69 was going to be different. Norman wanted to make a statement to that effect literally from day one. So he put together a truly grand grand opening – a week-long mini-festival of the arts, featuring live music, poetry, an art exhibit. Among its contributors was this techno-wizard guy that everybody called Stytch; he brought in his experimental art film…

Jim Stoyka: This voluptuous young lady agreed to do nude scenes with me, which kind of blew us away, but anyway, it worked out quite well. However, we found that she didn't look as sexy when she was nude than if she had her jeans on. And so what we did was, I sat cross-legged talking a blue streak. And then she came in, stage left, cracked an egg over my head, and then left stage right. And that was the opening credits of the film. Then it all went from there.

Making films is just one of Stytch’s many talents. His real forte is electronics. By the time he’s 16, Stytch and his buddy Richard are rummaging through the city dump, pulling apart old TV sets for their parts. Next thing you know, they’re running Winnipeg’s first – maybe Canada’s first – underground radio station.

JS: Yeah it was a basement radio station. Richard lived a couple blocks away. And he offered to have it at his place, because he had all the records. He had about 400 45s at the time. I guess we got together and started talking about putting together a radio station, because he had all these records and they weren't playing rock on the radio stations at that time, certainly not continuously.

– Did you know who was listening to you? Or did you have a sense of who you were connecting with?

Yes, because we gave out the telephone number and we had dedications. Once we were on the air, the family whose phone it was, they couldn't use the phone. It was rock solid. We were at the point where you could just hang up and then just pick it up again and say hello. And there's somebody there…

– This is pirate radio. Pirate radio… How long did you man the station so to speak…

Our hours were six o'clock till six till 10 or 11 – 10 every day except for the weekends, and on the weekends we went to midnight. And we did that every day. And every week. Once we started, we were on the air continuously, except when we saw a Department of Communications truck with all its antennas in the area, we shut down.

Jim Stoyka – Stytch, that is – came to Opus initially to set up the store’s audio system, including for the grand opening. With Stytch, Norman got more than he bargained for, and he loved it.

NS: I rented the place from Clifford’s Ladies Wear. There was a joint toilet between his staff, downstairs and mine. And my – I don't know what you would call him, a techno-engineer, to be more or less in the vein of Zappa and some others. He said, You know, there's a window there that goes into that small room. But we'll have to take the toilet out because I have to manipulate that.

JS: That became the projection room and there was this, we put a sound rack in there, a 19-inch sound rack. And a sound system. It was a 20 seat theatre as I recall. And so it wasn't very big. But all the headphones came back to a jack panel and I could patch in whatever soundtrack I wanted to each individual headphone.

So, everyone would take their seat and as the lights went down they’d be asked to put on their headphones. This is where the projectors kicked in. Older listeners might recall seeing one of those things in the classroom or maybe in a business meeting. You’d take your material – a map, a diagram, a business report – and project it onto a big white screen so you could present it to your audience. In the mid-60s, these same projectors started showing up at rock concerts – psychedelic rock concerts. You’d put some water in a curved glass dish, add in a few drops of different coloured oils, and then you’d slide the dish so the colours moved around and blended together, preferably in time with the music, and that would be projected onto a screen behind the band. If you were there, and if you were zonked out on acid or something, what you got was a light show – a mind-bending experience as it were… That’s exactly what our man Stytch was going for. Not with a band, in this case, but for his film.

JS: We presented the film on the first day, and it went over like a lead brick. It was called Nowhere Man. I was the lead actor, and it was about, we decided to give them what every – what we thought everybody thought hippies were all about. And, you know, so I was a dope-smoking hippie, and then I’d go to this girl’s place and I’d undress her – and nothing happened. I just undid her buttons – thirty buttons on this stupid thing and I couldn't get them undone. And so that's what made the movie very boring. But I'm very realistic. It is. But to spice it up. We decided, okay, well let's bring in the light projectors. And let's mask the film with the light projectors. So we did. And once we did that, well, this