Discover The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast

The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast

The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast

Author: Stuart Winchester

Subscribed: 141Played: 6,223Subscribe

Share

© Stuart Winchester

Description

239 Episodes

Reverse

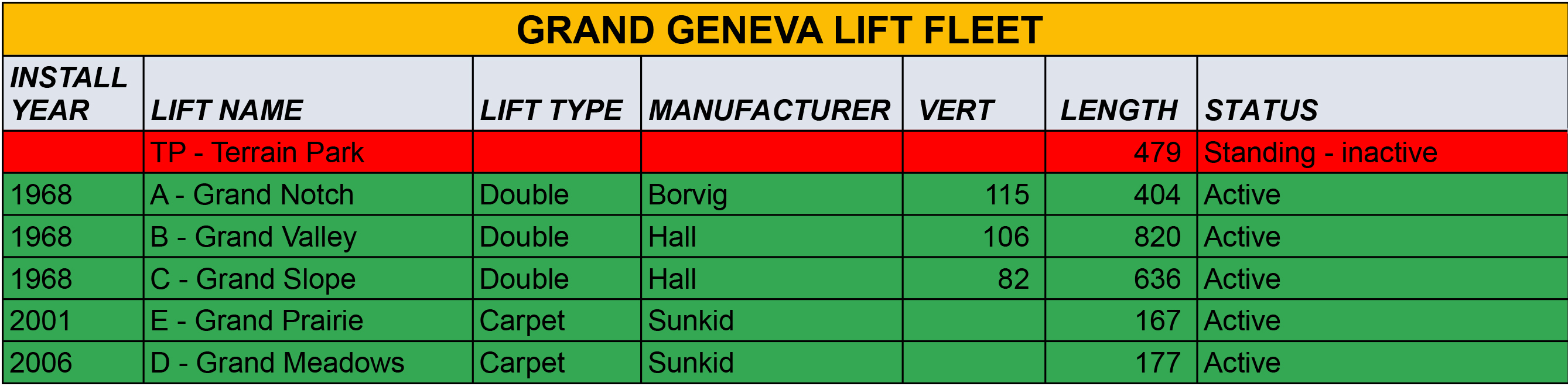

WhoRyan Brown, Director of Golf & Ski at The Mountaintop at Grand Geneva, WisconsinRecorded onJune 17, 2025About the Mountaintop at Grand GenevaClick here for a mountain stats overviewOwned by: Marcus HotelsLocated in: Lake Geneva, WisconsinYear founded: 1968Pass affiliations: NoneClosest neighboring U.S. ski areas: Alpine Valley (:23), Wilmot Mountain (:29), Crystal Ridge (:48), Alpine Hills Adventure Park (1:04)Base elevation: 847 feetSummit elevation: 962 feetVertical drop: 115 feetSkiable acres: 30Average annual snowfall: 34 inchesTrail count: 21 (41% beginner, 41% intermediate, 18% advanced)Lift count: 6 (3 doubles, 1 ropetow, 2 carpets)Why I interviewed himOf America’s various mega-regions, the Midwest is the quietest about its history. It lacks the quaint-town Colonialism and Revolutionary pride of the self-satisfied East, the cowboy wildness and adobe earthiness of the West, the defiant resentment of the Lost Glory South. Our seventh-grade Michigan History class stapled together the state’s timeline mostly as a series of French explorers passing through on their way to somewhere more interesting. They were followed by a wave of industrial loggers who mowed the primeval forests into pancakes. Then the factories showed up. And so the state’s legacy was framed not as one of political or cultural or military primacy, but of brand, the place that stamped out Chevys and Fords by the tens of millions.To understand the Midwest, then, we must look for what’s permanent. The land itself won’t do. It’s mostly soil, mostly flat. Great for farming, bad for vistas. Dirt doesn’t speak to the soul like rock, like mountains. What humans built doesn’t tell us a much better story. Everything in the Midwest feels too new to conceal ghosts. The largest cities rose late, were destroyed in turn by fires and freeways, eventually recharged with arenas and glass-walled buildings that fail to echo or honor the past. Nothing lasts: the Detroit Pistons built the Palace of Auburn Hills in 1988 and developers demolished it 32 years later; the Detroit Lions (and, for a time, the Pistons) played at the Pontiac Silverdome, a titanic, 82,600-spectator stadium that opened in 1976 and came down in 2013 (37 years old). History seemed to bypass the region, corralling the major wars to the east and shooing the natural disasters to the west and south. Even shipwrecks lose their doubloons-and-antique-cannons romance in the Midwest: the Great Lakes most famous downed vessel, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, sank into Lake Superior in 1975. Her cargo was 26,535 tons of taconite ore pellets. A sad story, but not exactly the sinking of the Titanic.Our Midwest ancestors did leave us one legacy that no one has yet demolished: names. Place names are perhaps the best cultural relics of the various peoples who occupied this land since the glaciers retreated 12,000-ish years ago. Thousands of Midwest cities, towns, and counties carry Native American names. “Michigan” is derived from the Algonquin “Mishigamaw,” meaning “big lake”; “Minnesota” from the Sioux word meaning “cloudy water.” The legacies of French explorers and missionaries live on in “Detroit” (French for “strait”), “Marquette” (17th century French missionary Jacques Marquette), and “Eau Claire” (“clear water”).But one global immigration funnel dominated what became the modern Midwest: 50 percent of Wisconsin’s population descends from German, Nordic, or Scandinavian countries, who arrived in waves from the Colonial era through the early 1900s. The surnames are everywhere: Schmitz and Meyer and Webber and Schultz and Olson and Hanson. But these Old-Worlders came a bit late to name the cities and towns. So they named what they built instead. And they built a lot of ski areas. Ten of Wisconsin’s 34 ski areas carry names evocative of Europe’s cold regions, Scandinavia and the Alps:I wonder what it must have been like, in 18-something-or-other, to leave a place where the Alps stood high on the horizon, where your family had lived in the same stone house for centuries, and sail for God knows how many weeks or months across an ocean, and slow roll overland by oxen cart or whatever they moved about in back then, and at the end of this great journey find yourself in… Wisconsin? They would have likely been unprepared for the landscape aesthetic. Tourism is a modern invention. “The elite of ancient Egypt spent their fortunes building pyramids and having their corpses mummified, but none of them thought of going shopping in Babylon or taking a skiing holiday in Phoenicia [partly in present-day Lebanon, which is home to as many as seven ski areas],” Yuval Noah Harari writes in Sapiens his 2015 “brief history of humankind.” Imagine old Friedrich, who had never left Bavaria, reconstituting his world in the hillocks and flats of the Midwest.Nothing against Wisconsin, but fast-forward 200 years, when the robots can give us a side-by-side of the upper Midwest and the European Alps, and it’s pretty clear why one is a global tourist destination and the other is known mostly as a place that makes a lot of cheese. And well you can imagine why Friedrich might want to summon a little bit of the old country to the texture of his life in the form of a ski area name. That these two worlds - the glorious Alps and humble Wisconsin skiing - overlap, even in a handful of place names, suggests a yearning for a life abandoned, a natural act of pining by a species that was not built to move their life across timezones.This is not a perfect analysis. Most – perhaps none – of these ski areas was founded by actual immigrants, but by their descendants. The Germanic languages spoken by these immigrant waves did not survive assimilation. But these little cultural tokens did. The aura of ancestral place endured when even language fell away. These little ski areas honor that.And by injecting grandiosity into the everyday, they do something else. In coloring some of the world’s most compact ski centers with the aura of some of its most iconic, their founders left us a message: these ski areas, humble as they are, matter. They fuse us to the past and they fuse us to the majesty of the up-high, prove to us that skiing is worth doing anywhere that it can be done, ensure that the ability to move like that and to feel the things that movement makes you feel are not exclusive realms fenced into the clouds, somewhere beyond means and imagination.Which brings us to Grand Geneva, a ski area name that evokes the great Swiss gateway city to the Alps. Too bad reality rarely matches up with the easiest narrative. The resort draws its name from the nearby town of Lake Geneva, which a 19th-century surveyor named not after the Swiss city, but after Geneva, New York, a city (that is apparently named after Geneva, Switzerland), on the shores of Seneca Lake, the largest of the state’s 11 finger lakes. Regardless, the lofty name was the fifth choice for a ski area originally called “Indian Knob.” That lasted three years, until the ski area shuttered and re-opened as the venerable Playboy Ski Area in 1968. More regrettable names followed – Americana Resort from 1982 to ’93, Hotdog Mountain from 1992 to ’94 – before going with the most obvious and least-questionable name, though its official moniker, “The Mountaintop at Grand Geneva” is one of the more awkward names in American skiing.None of which explains the principal question of this sector: why I interviewed Mr. Brown. Well, I skied a bunch of Milwaukee bumps on my drive up to Bohemia from Chicago last year, this was one of them, and I thought it was a cute little place. I also wondered how, with its small-even-for-Wisconsin vertical drop and antique lift collection, the place had endured in a state littered with abandoned ski areas. Consider it another entry into my ongoing investigation into why the ski areas that you would not always expect to make it are often the ones that do.What we talked aboutFighting the backyard effect – “our customer base – they don’t really know” that the ski areas are making snow; a Chicago-Milwaukee-Madison bullseye; competing against the Vail-owned mountain to the south and the high-speed-laced ski area to the north; a golf resort with a ski area tacked on; “you don’t need a big hill to have a great park”; brutal Midwest winters and the escape of skiing; I attempt to talk about golf again and we’re probably done with that for a while; Boyne Resorts as a “top golf destination”; why Grand Geneva moved its terrain park; whether the backside park could re-open; “we’ve got some major snowmaking in the works”; potential lift upgrades; no bars on the lifts; the ever-tradeoff between terrain parks and beginner terrain; the ski area’s history as a Playboy Club and how the ski hill survived into the modern era; how the resort moves skiers to the hill with hundreds of rooms and none of them on the trails; thoughts on Indy Pass; and Lake Geneva lake life.What I got wrongWe recorded this conversation prior to Sunburst’s joining Indy Pass, so I didn’t mention the resort when discussing Wisconsin ski areas on the product.Podcast NotesOn the worst season in the history of the MidwestI just covered this in the article that accompanied the podcast on Treetops, Michigan, but I’ll summarize it this way: the 2023-24 ski season almost broke the Midwest. Fortunately, last winter was better, and this year is off to a banging start.On steep terrain beneath lift AI just thought this was a really unexpected and cool angle for such a little hill. On the Playboy ClubFrom SKI magazine, December 1969:It is always interesting when giants merge. Last winter Playboy magazine (5.5 million readers) and the Playboy Club (19 swinging nightclubs from Hawaii to New York to Jamaica, with 100,000 card-carrying members) in effect joined the sport of skiing, which is also a large, but less formal, structure of 3.5 million lift-ticket-carrying members. The resulting conglomerate was the Lake Geneva Playboy Club-Hotel, P

WhoMike Giorgio, Vice President and General Manager of Stowe Mountain, VermontRecorded onOctober 8, 2025About StoweClick here for a mountain stats overviewOwned by: Vail Resorts, which also owns:Located in: Stowe, VermontYear founded: 1934Pass affiliations:* Epic Pass: unlimited access* Epic Local Pass: unlimited access with holiday blackouts* Epic Northeast Value Pass: 10 days with holiday blackouts* Epic Northeast Midweek Pass: 5 midweek days with holiday blackouts* Access on Epic Day Pass All and 32 Resort tiers* Ski Vermont 4 Pass – up to one day, with blackouts* Ski Vermont Fifth Grade Passport – 3 days, with blackoutsClosest neighboring U.S. ski areas: Smugglers’ Notch (ski-to or 40-ish-minute drive in winter, when route 108 is closed over the notch), Bolton Valley (:45), Cochran’s (:50), Mad River Glen (:55), Sugarbush (:56)Base elevation: 1,265 feet (at Toll House double)Summit elevation: 3,625 feet (top of the gondola), 4,395 feet at top of Mt. MansfieldVertical drop: 2,360 feet lift-served, 3,130 feet hike-toSkiable acres: 485Average annual snowfall: 314 inchesTrail count: 116 (16% beginner, 55% intermediate, 29% advanced)Lift count: 12 (1 eight-passenger gondola, 1 six-passenger gondola, 1 six-pack, 3 high-speed quads, 1 fixed-grip quad, 1 triple, 2 doubles, 2 carpets)Why I interviewed himThere is no Aspen of the East, but if I had to choose an Aspen of the East, it would be Stowe. And not just because Aspen Mountain and Stowe offer a similar fierce-down, with top-to-bottom fall-line zippers and bumpy-bumps spliced by massive glade pockets. Not just because each ski area rises near the far end of densely bunched resorts that the skier must drive past to reach them. Not just because the towns are similarly insular and expensive and tucked away. Not just because the wintertime highway ends at both places, an anachronistic act of surrender to nature from a mechanized world accustomed to fencing out the seasons. And not just because each is a cultural stand-in for mechanized skiing in a brand-obsessed, half-snowy nation that hates snow and is mostly filled with non-skiers who know nothing about the activity other than the fact that it exists. Everyone knows about Aspen and Stowe even if they’ll never ski, in the same way that everyone knows about LeBron James even if they’ve never watched basketball.All of that would be sufficient to make the Stowe-is-Aspen-East argument. But the core identity parallel is one that threads all these tensions while defying their assumed outcome. Consider the remoteness of 1934 Stowe and 1947 Aspen, two mountains in the pre-snowmaking, pre-interstate era, where cutting a ski area only made sense because that’s where it snowed the most. Both grew in similar fashion. First slowly toward the summit with surface lifts and mile-long single chairs crawling up the incline. Then double chairs and gondolas and snowguns and detachable chairlifts. A ski area for the town evolves into a ski area for the world. Hotels a la luxe at the base, traffic backed up to the interstate, corporate owners and $261 lift tickets.That sounds like a formula for a ruined world. But Stowe the ski area, like Aspen Mountain the ski area, has never lost its wild soul. Even buffed out and six-pack equipped and Epic Pass-enabled, Stowe remains a hell of a mountain, one of the best in New England, one of my favorite anywhere. With its monster snowfalls, its endless and perfectly spaced glades, its never-groomed expert zones, its sprawling footprint tucked beneath the Mansfield summit, its direct access to rugged and forbidding backcountry, Stowe, perhaps the most western-like mountain in the East, remains a skier’s mountain, a fierce and humbling proving ground, an any-skier’s destination not because of its trimmings, but because of the Christmas tree itself.Still, Stowe will never be Aspen, because Stowe does not sit at 8,000 feet and Stowe does not have three accessory ski areas and Stowe the Town does not grid from the lift base like Aspen the Town but rather lies eight miles down the road. Also Stowe is owned by Vail Resorts, and can you just imagine? But in a cultural moment that assumes ski area ruination-by-the-consolidation-modernization-mega-passification axis-of-mainstreaming, Aspen and Stowe tell mirrored versions of a more nuanced story. Two ski areas, skinned in the digital-mechanical infrastructure that modernity demands, able to at once accommodate the modern skier and the ancient mountain, with all of its quirks and character. All of its amazing skiing.What we talked aboutStowe the Legend; Vail Resorts’ leadership carousel; ascending to ski area leadership without on-mountain experience; Mount Brighton, Michigan and Midwest skiing; struggles at Paoli Peaks, Indiana; how the Sunrise six-pack upgrade of the old Mountain triple changed the mountain; whether the Four Runner quad could ever become a six-pack; considering the future of the Lookout Double and Mansfield Gondola; who owns the land in and around the ski area; whether Stowe has terrain expansion potential; the proposed Smugglers’ Notch gondola connection and whether Vail would ever buy Smuggs; “you just don’t understand how much is here until you’re here”; why Stowe only claims 485 acres of skiable terrain; protecting the Front Four; extending Stowe’s season last spring; snowmaking in a snowbelt; the impact and future of paid parking; on-mountain bed-base potential; Epic Friend 50 percent off lift tickets; and Stowe locals and the Epic Pass.What I got wrongOn detailsI noted that one of my favorite runs was not a marked run at all: the terrain beneath the Lookout double chair. In fact, most of the trail beneath this mile-plus-long lift is a market run called, uh, “Lookout.” So I stand corrected. However, the trailmap makes this full-throttle, narrow bumper – which feels like skiing on a rising tide – look wide, peaceful, and groomable. It is none of those things, at least for its first third or so.On skiable acres* I said that Killington claimed “like 1,600 acres” of terrain – the exact claimed number is 1,509 acres.* I said that Mad River Glen claimed far fewer skiable acres than it probably could, but I was thinking of an out-of-date stat. The mountain claims just 115 acres of trails – basically nothing for a 2,000-vertical-foot mountain, but also “800 acres of tree-skiing access.” The number listed on the Pass Smasher Deluxe is 915 acres.On season closingsI intimated that Stowe had always closed the third weekend in April. That appears to be mostly true for the past two-ish decades, which is as far back as New England Ski History has records. The mountain did push late once, however, in 2007, and closed early during the horrible no-snow winter of 2011-12 (April 1), and the Covid-is-here-to-kill-us-all shutdown of 2020 (March 14).On doing better prepI asked whether Stowe had considered making its commuter bus free, but it, um, already is. That’s called Reeserch, Folks.On lift ticket ratesI claimed that Stowe’s top lift ticket price would drop from $239 last year to $235 this coming season, but that’s inaccurate. Upon further review, the peak walk-up rate appears to be increasing to $261 this coming winter:Which means Vail’s record of cranking Stowe lift ticket rates up remains consistent:On opening hoursI said that the lifts at Stowe sometimes opened at “7:00 or 7:30,” but the earliest ski lift currently opens at 8:00 most mornings (the Over Easy transit gondola opens at 7:30). The Fourrunner quad used to open at 7:30 a.m. on weekends and holidays. I’m not sure when mountain ops changed that. Here’s the lift schedule clipped from the circa 2018 trailmap:On Mount Brighton, Michigan’s supposed trashheap legacyI’d read somewhere, sometime, that Mount Brighton had been built on dirt moved to make way for Interstate 96, which bores across the state about a half mile north of the ski area. The timelines match, as this section of I-96 was built between 1956 and ’57, just before Brighton opened in 1960. This circa 1962 article from The Livingston Post, a local paper, fails to mention the source of the dirt, leaving me uncertain as to whether or not the hill is related to the highway:Why you should ski StoweFrom my April 10 visit last winter, just cruising mellow, low-angle glades nearly to the base:I mean, the place is just:I love it, Man. My top five New England mountains, in no particular order, are Sugarbush, Stowe, Jay, Smuggs, and Sugarloaf. What’s best on any given day depends on conditions and crowding, but if you only plan to ski the East once, that’s your list.Podcast NotesOn Stowe being the last 1,000-plus-vertical-foot Vermont ski area that I featured on the podYou can view the full podcast catalogue here. But here are the past Vermont eps:* Killington & Pico – 2019 | 2023 | 2025* Stratton 2024* Okemo 2023* Middlebury Snowbowl 2023* Mount Snow 2020 | 2023* Bromley 2022* Jay Peak 2022 | 2020* Smugglers’ Notch 2021* Bolton Valley 2021* Hermitage Club 2020* Sugarbush 2020 with current president John Hammond | 2020 with past owner Win Smith* Mad River Glen 2020* Magic Mountain 2019 | 2020* Burke 2019On Stowe having “peers, but no betters” in New EnglandWhile Stowe doesn’t stand out in any one particular statistical category, the whole of the place stacks up really well to the rest of New England - here’s a breakdown of the 63 public ski areas that spin chairlifts across the six-state region:On the Front Four ski runsThe “Front Four” are as synonymous with Stowe as the Back Bowls are with Vail Mountain or Corbet’s Couloir is with Jackson Hole. These Stowe trails are steep, narrow, double-plus-fall-line bangers that, along with Castlerock at Sugarbush and Paradise at Mad River Glen, are among the most challenging runs in New England.The problem is determining which of the double-blacks spiderwebbing off the top of Fourrunner are part of the Front Four. Officially, the designation has always bucketed National, Liftline, Goat, and Starr tog

The Storm explores the world of lift-served skiing year-round. Join us.WhoLonie Glieberman, Founder, Owner, & President of Mount Bohemia, MichiganRecorded onNovember 19, 2025About Mount BohemiaClick here for a mountain stats overviewOwned by: Lonie GliebermanLocated in: Lac La Belle, MichiganYear founded: 2000, by LoniePass affiliations: NoneReciprocal partners: Boho has developed one of the strongest reciprocal pass programs in the nation, with lift tickets to 34 partner mountains. To protect the mountain’s more distant partners from local ticket-hackers, those ski areas typically exclude in-state and border-state residents from the freebies. Here’s the map:And here’s the Big Dumb Storm Chart detailing each mountain and its Boho access:Closest neighboring ski areas: Mont Ripley (:50)Base elevation: 624 feetSummit elevation: 1,522 feetVertical drop: 898 feetSkiable acres: 585Average annual snowfall: 273 inchesTrail count: It’s hard to say exactly, as Boho adds new trails every year, and its map is one of the more confusing ones in American skiing, both as you try analyzing it on this screen, and as you’re actually navigating the mountain. My advice is to not try too hard to make the trailmap make sense. Everything is skiable with enough snow, and no matter what, you’re going to end up back at one of the two chairlifts or the road, where a shuttlebus will come along within a few minutes.Lift count: 2 (1 triple, 1 double)Why I interviewed himFor those of us who lived through a certain version of America, Mount Bohemia is a fever dream, an impossible thing, a bantered-about-with-friends-in-a-basement-rec-room-idea that could never possibly be. This is because we grew up in a world in which such niche-cool things never happened. Before the internet spilled from the academic-military fringe into the mainstream around 1996, We The Commoners fed our brains with a subsistence diet of information meted out by institutional media gatekeepers. What I mean by “gatekeepers” is the limited number of enterprises who could afford the broadcast licenses, printing presses, editorial staffs, and building and technology infrastructure that for decades tethered news and information to costly distribution mechanisms.In some ways this was a better and more reliable world: vetted, edited, fact-checked. Even ostensibly niche media – the Electronic Gaming Monthly and Nintendo Power magazines that I devoured monthly – emerged from this cubicle-in-an-office-tower Process that guaranteed a sober, reality-based information exchange.But this professionalized, high-cost-of-entry, let’s-get-Bob’s-sign-off-before-we-run-this, don’t-piss-off-the-advertisers world limited options, which in turn limited imaginations – or at least limited the real-world risks anyone with money was willing to take to create something different. We had four national television networks and a couple dozen cable channels and one or two local newspapers and three or four national magazines devoted to niche pursuits like skiing. We had bookstores and libraries and the strange, ephemeral world of radio. We had titanic, impossible-to-imagine-now big-box chain stores ordering the world’s music and movies into labelled bins, from which shoppers could hope – by properly interpreting content from box-design flare or maybe just by luck – to pluck some soul-altering novelty.There was little novelty. Or at least, not much that didn’t feel like a slightly different version of something you’d already consumed. Everything, no matter how subversive its skin, had to appeal to the masses, whose money was required to support the enterprise of content creation. Pseudo-rebel networks such as ESPN and MTV quickly built global brands by applying the established institutional framework of network television to the mainstream-but-information-poor cultural centerpieces of sports and music.This cultural sameness expressed itself not just in media, but in every part of life: America’s brand-name sprawl-ture (sprawl culture) of restaurants and clothing stores and home décor emporia; its stuff-freeways-through-downtown ruining of our great cities; its three car companies stamping out nondescript sedans by the millions.Skiing has long acted as a rebel’s escape from staid American culture, but it has also been hemmed in by it. Yes, said Skiing Incorporated circa 1992, we can allow a photo of some fellow jumping off a cliff if it helps convince Nabisco Bob fly his family out to Colorado for New Year’s, so long as his family is at no risk of actually locating any cliffs to jump off of upon arrival. After all, 1992 Bob has no meaningful outlet through which to highlight this advertising-experience disconnect. The internet broke this whole system. Everywhere, for everything. If I wanted, say, a Detroit Pistons hoodie in 1995, I had to drive to a dozen stores and choose the least-bad version from the three places that stocked them. Today I have far more choice at far less hassle: I can browse hundreds of designs online without leaving the house. Same for office furniture or shoes or litterboxes or laundry baskets or cars. And especially for media and information. Consumer choice is greater not only because the internet eliminated distance, but also because it largely eliminated the enormous costs required to actualize a tangible thing from the imagination.There were trade-offs, of course. Our current version of reality has too many options, too many poorly made products, too much bad information. But the internet did a really good job of democratizing preferences and uniting dispersed communities around niche interests. Yes, this means that a global community of morons can assemble over their shared belief that the planet is flat, but it also means that legions of Star Wars or Marvel Comics or football obsessives can unite to demand more of these specific things. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the dormant Star Wars and Marvel franchises rebooted in spectacular, omnipresent fashion within a decade of the .com era’s dawn.The trajectory was slightly different in skiing. The big-name ski areas today are largely the same set of big-name ski areas that we had 30 years ago, at least in America (Canada is a very different story). But what the internet helped bring to skiing was an awareness that the desire for turns outside of groomed runs was not the hyper-specific desire of the most dedicated, living-in-a-campervan-with-their-dog skiers, but a relatively mainstream preference. Established ski areas adapted, adding glades and terrain parks and ungroomed zones. The major ski areas of 2025 are far more interesting versions of the ski areas that existed under the same names in 1995.Dramatic and welcome as these additions were, they were just additions. No ski area completely reversed itself and shut out the mainstream skier. No one stopped grooming or eliminated their ski school or stopped renting gear. But they did act as something of a proof-of-concept for minimalist ski areas that would come online later, including avy-gear-required, no-grooming Silverton, Colorado in 2001, and, at the tip-top of the American Midwest, in a place too remote for anyone other than industrial mining interests to bother with, the ungroomed, snowmaking-free Mount Bohemia.I can’t draw a direct line between the advent of the commercial internet and the rise of Mount Bohemia as a successful niche business within a niche industry. But I find it hard to imagine one without the other. The pre-internet world, the one that gave us shopping malls and laugh-track sitcoms and standard manual transmissions, lacked the institutional imagination to actualize skiing’s most dynamic elements in the form of a wild and remote pilgrimage site. Once the internet ordered fringe freeskiing sentiments into a mainstream coalition, the notion of an extreme ski area seemed inevitable. And Bohemia, without a basically free global megaphone to spread word of its improbable existence, would struggle to establish itself in a ski industry that dismissed the concept as idiotic and with a national ski media that considered the Midwest irrelevant.Even with the internet, Boho took a while to catch on, as Lonie detailed in his first podcast appearance three years ago. It probably took the mainstreaming of social media, starting around 2008, to really amp up the online echo-sphere and help skiers understand this gladed, lake-effect-bombed kingdom at the end of the world.Whatever drove Boho’s success, that success happened. This is a good, stable business that proved that ski areas do not have to cater to all skiers to be viable. But those of us who wanted Bohemia before it existed still have a hard time believing that it does. Like superhero movies or video-calls or energy drinks that aren’t coffee, Boho is a thing we could, in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, easily imagine but just as easily dismiss as fantasy.Fortunately, our modern age of invention and experimentation includes plenty of people who dismiss the dismissers, who see things that don’t exist yet and bring them into our world. And one of the best contributions to skiing to emerge from this age is Mount Bohemia.What we talked aboutSeason pass price and access changes; lifetime and two-year season passes; a Disney-ski comparison that isn’t negative; when your day ticket costs as much as your season pass; Lonie’s dog makes a cameo; not selling lift tickets on Saturdays; “too many companies are busy building a brand that no one will hate, versus a brand that someone will love”; why it’s OK to have some people be angry with you; UP skiing’s existential challenge; skiing’s vibe shift from competition to complementary culture; the Midwest’s advanced-skier problem; Boho’s season pass reciprocal program; why ski areas survive; the Keweenaw snow stake and Boho’s snowfall history; recent triple chair improvements and why Boho didn’t fully replace the chair – “it’s basically a brand-new chairlift”; a novel idea for B

WhoDeb Hatley, Owner of Hatley Pointe, North CarolinaRecorded onJuly 30, 2025About Hatley PointeClick here for a mountain stats overviewOwned by: Deb and David Hatley since 2023 - purchased from Orville English, who had owned and operated the resort since 1992Located in: Mars Hill, North CarolinaYear founded: 1969 (as Wolf Laurel or Wolf Ridge; both names used over the decades)Pass affiliations: Indy Pass, Indy+ Pass – 2 days, no blackoutsClosest neighboring ski areas: Cataloochee (1:25), Sugar Mountain (1:26)Base elevation: 4,000 feetSummit elevation: 4,700 feetVertical drop: 700 feetSkiable acres: 54Average annual snowfall: 65 inchesTrail count: 21 (4 beginner, 11 intermediate, 6 advanced)Lift count: 4 active (1 fixed-grip quad, 1 ropetow, 2 carpets); 2 inactive, both on the upper mountain (1 fixed-grip quad, 1 double)Why I interviewed herOur world has not one map, but many. Nature drew its own with waterways and mountain ranges and ecosystems and tectonic plates. We drew our maps on top of these, to track our roads and borders and political districts and pipelines and railroad tracks.Our maps are functional, simplistic. They insist on fictions. Like the 1,260-mile-long imaginary straight line that supposedly splices the United States from Canada between Washington State and Minnesota. This frontier is real so long as we say so, but if humanity disappeared tomorrow, so would that line.Nature’s maps are more resilient. This is where water flows because this is where water flows. If we all go away, the water keeps flowing. This flow, in turn, impacts the shape and function of the entire world.One of nature’s most interesting maps is its mountain map. For most of human existence, mountains mattered much more to us than they do now. Meaning: we had to respect these giant rocks because they stood convincingly in our way. It took European settlers centuries to navigate en masse over the Appalachians, which is not even a severe mountain range, by global mountain-range standards. But paved roads and tunnels and gas stations every five miles have muted these mountains’ drama. You can now drive from the Atlantic Ocean to the Midwest in half a day.So spoiled by infrastructure, we easily forget how dramatically mountains command huge parts of our world. In America, we know this about our country: the North is cold and the South is warm. And we define these regions using battle maps from a 19th Century war that neatly bisected the nation. Another imaginary line. We travel south for beaches and north to ski and it is like this everywhere, a gentle progression, a continent-length slide that warms as you descend from Alaska to Panama.But mountains disrupt this logic. Because where the land goes up, the air grows cooler. And there are mountains all over. And so we have skiing not just in expected places such as Vermont and Maine and Michigan and Washington, but in completely irrational ones like Arizona and New Mexico and Southern California. And North Carolina.North Carolina. That’s the one that surprised me. When I started skiing, I mean. Riding hokey-poke chairlifts up 1990s Midwest hills that wouldn’t qualify as rideable surf breaks, I peered out at the world to figure out where else people skied and what that skiing was like. And I was astonished by how many places had organized skiing with cut trails and chairlifts and lift tickets, and by how many of them were way down the Michigan-to-Florida slide-line in places where I thought that winter never came: West Virginia and Virginia and Maryland. And North Carolina.Yes there are ski areas in more improbable states. But Cloudmont, situated in, of all places, Alabama, spins its ropetow for a few days every other year or so. North Carolina, home to six ski areas spinning a combined 35 chairlifts, allows for no such ambiguity: this is a ski state. And these half-dozen ski centers are not marginal operations: Sugar Mountain and Cataloochee opened for the season last week, and they sometimes open in October. Sugar spins a six-pack and two detach quads on a 1,200-foot vertical drop.This geographic quirk is a product of our wonderful Appalachian Mountain chain, which reaches its highest points not in New England but in North Carolina, where Mount Mitchell peaks at 6,684 feet, 396 feet higher than the summit of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington. This is not an anomaly: North Carolina is home to six summits taller than Mount Washington, and 12 of the 20-highest in the Appalachians, a range that stretches from Alabama to Newfoundland. And it’s not just the summits that are taller in North Carolina. The highest ski area base elevation in New England is Saddleback, which measures 2,147 feet at the bottom of the South Branch quad (the mountain more typically uses the 2,460-foot measurement at the bottom of the Rangeley quad). Either way, it’s more than 1,000 feet below the lowest base-area elevation in North Carolina:Unfortunately, mountains and elevation don’t automatically equal snow. And the Southern Appalachians are not exactly the Kootenays. It snows some, sometimes, but not so much, so often, that skiing can get by on nature’s contributions alone - at least not in any commercially reliable form. It’s no coincidence that North Carolina didn’t develop any organized ski centers until the 1960s, when snowmaking machines became efficient and common enough for mass deployment. But it’s plenty cold up at 4,000 feet, and there’s no shortage of water. Snowguns proved to be skiing’s last essential ingredient.Well, there was one final ingredient to the recipe of southern skiing: roads. Back to man’s maps. Specifically, America’s interstate system, which steamrolled the countryside throughout the 1960s and passes just a few miles to Hatley Pointe’s west. Without these superhighways, western North Carolina would still be a high-peaked wilderness unknown and inaccessible to most of us.It’s kind of amazing when you consider all the maps together: a severe mountain region drawn into the borders of a stable and prosperous nation that builds physical infrastructure easing the movement of people with disposable income to otherwise inaccessible places that have been modified for novel uses by tapping a large and innovative industrial plant that has reduced the miraculous – flight, electricity, the internet - to the commonplace. And it’s within the context of all these maps that a couple who knows nothing about skiing can purchase an established but declining ski resort and remake it as an upscale modern family ski center in the space of 18 months.What we talked aboutHurricane Helene fallout; “it took every second until we opened up to make it there,” even with a year idle; the “really tough” decision not to open for the 2023-24 ski season; “we did not realize what we were getting ourselves into”; buying a ski area when you’ve never worked at a ski area and have only skied a few times; who almost bought Wolf Ridge and why Orville picked the Hatleys instead; the importance of service; fixing up a broken-down ski resort that “felt very old”; updating without losing the approachable family essence; why it was “absolutely necessary” to change the ski area’s name; “when you pulled in, the first thing that you were introduced to … were broken-down machines and school buses”; Bible verses and bare trails and busted-up everything; “we could have spent two years just doing cleanup of junk and old things everywhere”; Hatley Pointe then and now; why Hatley removed the double chair; a detachable six-pack at Hatley?; chairlifts as marketing and branding tools; why the Breakaway terrain closed and when it could return and in what form; what a rebuilt summit lodge could look like; Hatley Pointe’s new trails; potential expansion; a day-ski area, a resort, or both?; lift-served mountain bike park incoming; night-skiing expansion; “I was shocked” at the level of après that Hatley drew, and expanding that for the years ahead; North Carolina skiing is all about the altitude; re-opening The Bowl trail; going to online-only sales; and lessons learned from 2024-25 that will build a better Hatley for 2025-26.What I got wrongWhen we recorded this conversation, the ski area hadn’t yet finalized the name of the new green trail coming off of Eagle – it is Pat’s Way (see trailmap above).I asked if Hatley intended to install night-skiing, not realizing that they had run night-ski operations all last winter.Why now was a good time for this interviewPardon my optimism, but I’m feeling good about American lift-served skiing right now. Each of the past five winters has been among the top 10 best seasons for skier visits, U.S. ski areas have already built nearly as many lifts in the 2020s (246) as they did through all of the 2010s (288), and multimountain passes have streamlined the flow of the most frequent and passionate skiers between mountains, providing far more flexibility at far less cost than would have been imaginable even a decade ago.All great. But here’s the best stat: after declining throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, the number of active U.S. ski areas stabilized around the turn of the century, and has actually increased for five consecutive winters:Those are National Ski Areas Association numbers, which differ slightly from mine. I count 492 active ski hills for 2023-24 and 500 for last winter, and I project 510 potentially active ski areas for the 2025-26 campaign. But no matter: the number of active ski operations appears to be increasing.But the raw numbers matter less than the manner in which this uptick is happening. In short: a new generation of owners is resuscitating lost or dying ski areas. Many have little to no ski industry experience. Driven by nostalgia, a sense of community duty, plain business opportunity, or some combination of those things, they are orchestrating massive ski area modernization projects, funded via their own wealth – typically earned via other enterprises – or by rallying a donor base.Exampl

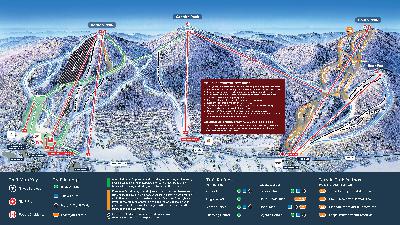

WhoWes Kryger, President and Ayden Wilber, Vice President of Mountain Operations at Greek Peak, New YorkRecorded onJune 30, 2025About Greek PeakClick here for a mountain stats overviewOwned by: John MeierLocated in: Cortland, New YorkYear founded: 1957 – opened Jan. 11, 1958Pass affiliations: Indy Pass, Indy+ Pass – 2 daysClosest neighboring U.S. ski areas: Labrador (:30), Song (:31)Base elevation: 1,148 feetSummit elevation: 2,100 feetVertical drop: 952 feetSkiable acres: 300Average annual snowfall: 120 inchesTrail count: 46 (10 easier, 16 more difficult, 15 most difficult, 5 expert, 4 terrain parks)Lift count: 8 (1 fixed-grip quad, 2 triples, 3 doubles – view Lift Blog’s inventory of Greek Peak’s lift fleet)Why I interviewed themNo reason not to just reprint what I wrote about the bump earlier this year:All anyone wants from a family ski trip is this: not too far, not too crowded, not too expensive, not too steep, not too small, not too Bro-y. Terrain variety and ample grooming and lots of snow, preferably from the sky. Onsite lodging and onsite food that doesn’t taste like it emerged from the ration box of a war that ended 75 years ago. A humane access road and lots of parking. Ordered liftlines and easy ticket pickup and a big lodge to meet up and hang out in. We’re not too picky you see but all that would be ideal.My standard answer to anyone from NYC making such an inquiry has been “hahaha yeah get on a plane and go out West.” But only if you purchased lift tickets 10 to 16 months in advance of your vacation. Otherwise you could settle a family of four on Mars for less than the cost of a six-day trip to Colorado. But after MLK Weekend, I have a new answer for picky non-picky New Yorkers: just go to Greek Peak.Though I’d skied here in the past and am well-versed on all ski centers within a six-hour drive of Manhattan, it had not been obvious to me that Greek Peak was so ideally situated for a FamSki. Perhaps because I’d been in Solo Dad tree-skiing mode on previous visits and perhaps because the old trailmap presented the ski area in a vertical fortress motif aligned with its mythological trail-naming scheme:But here is how we experienced the place on one of the busiest weekends of the year:1. No lines to pick up tickets. Just these folks standing around in jackets, producing an RFID card from some clandestine pouch and syncing it to the QR code on my phone.2. Nothing resembling a serious liftline outside of the somewhat chaotic Visions “express” (a carpet-loaded fixed-grip quad). Double and triple chairs, scattered at odd spots and shooting off in all directions, effectively dispersing skiers across a broad multi-faced ridge. The highlight being this double chair originally commissioned by Socrates in 407 B.C.:3. Best of all: endless, wide-open, uncrowded top-to-bottom true greens – the only sort of run that my entire family can ski both stress-free and together.Those runs ambled for a thousand vertical feet. The Hope Lake Lodge, complete with waterpark and good restaurant, sits directly across the street. A shuttle runs back and forth all day long. Greek Peak, while deeper inland than many Great Lakes-adjacent ski areas, pulls steady lake-effect, meaning glades everywhere (albeit thinly covered). It snowed almost the entire weekend, sometimes heavily. Greek Peak’s updated trailmap better reflects its orientation as a snowy family funhouse (though it somewhat obscures the mountain’s ever-improving status as a destination for Glade Bro):For MLK 2024, we had visited Camelback, seeking the same slopeside-hotel-with-waterpark-decent-food-family-skiing combo. But it kinda sucked. The rooms, tinted with an Ikea-by-the-Susquehanna energy, were half the size of those at Greek Peak and had cost three times more. Our first room could have doubled as the smoking pen at a public airport (we requested, and received, another). The hill was half-open and overrun with people who seemed to look up and be genuinely surprised to find themselves strapped to snoskis. Mandatory parking fees even with a $600-a-night room; mandatory $7-per-night, per-skier ski check (which I dodged); and perhaps the worst liftline management I’ve ever witnessed had, among many other factors, added up to “let’s look for something better next year.”That something was Greek Peak, though the alternative only occurred to me when I attended an industry event at the resort in September and re-considered its physical plant undistracted by ski-day chaos. Really, this will never be a true alternative for most NYC skiers – at four hours from Manhattan, Greek Peak is the same distance as far larger Stratton or Mount Snow. I like both of those mountains, but I know which one I’m driving my family to when our only time to ski together is the same time that everyone else has to ski together.What we talked about116,000 skier visits; two GP trails getting snowmaking for the first time; top-to-bottom greens; Greek Peak’s family founding in the 1950s – “any time you told my dad [Al Kryger] he couldn’t do it, he would do it just to prove you wrong”; reminiscing on vintage Greek Peak; why Greek Peak made it when similar ski areas like Scotch Valley went bust; the importance of having “hardcore skiers” run a ski area; does the interstate matter?; the unique dynamics of working in – and continuing – a family business; the saga and long-term impact of building a full resort hotel across the street from the ski area; “a ski area is liking running a small municipality”; why the family sold the ski area more than half a century after its founding; staying on at the family business when it’s no longer a family business; John Meier arrives; why Greek Peak sold Toggenburg; long-term snowmaking ambitions; potential terrain expansion – where and how much; “having more than one good ski season in a row would be helpful” in planning a future expansion; how Greek Peak modernized its snowmaking system and cut its snowmaking hours in half while making more snow; five times more snowguns; Great Lakes lake-effect snow; Greek Peak’s growing glade network and long evolution from a no-jumps-allowed old-school operation to today’s more freewheeling environment; potential lift upgrades; why Greek Peak is unlikely to ever have a high-speed lift; keeping a circa 1960s lift made by an obscure company running; why Greek Peak replaced an old double with a used triple on Chair 3 a few years ago; deciding to renovate or replace a lift; how the Visions 1A quad changed Greek Peak and where a similar lift could make sense; why Greek Peak shortened Chair 2; and the power of Indy Pass for small, independent ski areas.What I got wrongOn Scotch Valley ski areaI said that Scotch Valley went out of business “in the late ‘90s.” As far as I can tell, the ski area’s last year of operation was 1998. At its peak, the 750-vertical-foot ski area ran a triple chair and two doubles serving a typical quirky-fun New York trail network. I’m sorry I missed skiing this one. Interestingly, the triple chair still appears to operate as part of a summer camp. I wish they would also run a winter camp called “we’re re-opening this ski area”:On ToggenburgI paraphrased a quote from Greek Peak owner John Meier, from a story I wrote around the 2021 closing of Toggenburg. Here’s the quote in full:“Skiing doesn’t have to happen in New York State,” Meier said. “It takes an entrepreneur, it takes a business investor. You gotta want to do it, and you’re not going to make a lot of money doing it. You’re going to wonder why are you doing this? It’s a very difficult business in general. It’s very capital-intensive business. There’s a lot easier ways to make a buck. This is a labor of love for me.”And here’s the full story, which lays out the full Togg saga:Podcast NotesOn Hope Lake Lodge and New York’s lack of slopeside lodgingI’ve complained about this endlessly, but it’s strange and counter-environmental that New York’s two largest ski areas offer no slopeside lodging. This is the same oddball logic at work in the Pacific Northwest, which stridently and reflexively opposes ski area-adjacent development in the name of preservation without acknowledging the ripple effects of moving 5,000 day skiers up to the mountain each winter morning. Unfortunately Gore and Whiteface are on Forever Wild land that would require an amendment to the state constitution to develop, and that process is beholden to idealistic downstate voters who like the notion of preservation enough to vote abstractly against development, but not enough to favor Whiteface over Sugarbush when it’s time to book a family ski trip and they need convenient lodging. Which leaves us with smaller mountains that can more readily develop slopeside buildings: Holiday Valley and Hunter are perhaps the most built-up, but West Mountain has a monster development grinding through local permitting processes: Greek Peak built the brilliant Hope Lake Lodge, a sprawling hotel/waterpark with wood-trimmed, fireplace-appointed rooms directly across the street from the ski area. A shuttle connects the two.On the “really, really bad” 2015 seasonWilber referred to the “really, really bad” 2015 season. Here’s the Kottke end-of-season stats comparing 2015-16 snowfall to the previous three winters, where you can see the Northeast just collapse into an abyss:Month-by-month (also from Kottke):Fast forward to Kottke’s 2022-23 report, and you can see just how terrible 2015-16 was in terms of skier visits compared to the seasons immediately before and after:On Greek Peak’s old masterplan with a chair 6I couldn’t turn up the masterplan that Kryger referred to with a Chair 6 on it, but the trailmap did tease a potential expansion from around 2006 to 2012, labelled as “Greek Peak East”:On Great Lakes lake-effect snow This is maybe the best representation I’ve found of the Great Lakes’ lake-effect snowbands:On Greek Peak’s Lift 2What a joy this thing is to ride:An absolute time machine:The lift, built in 1

WhoBarry Owens, General Manager of Treetops, MichiganRecorded onJune 13, 2025About TreetopsClick here for a mountain stats overviewOwned by: Treetops Acquisition Company LLCLocated in: Gaylord, MichiganYear founded: 1954Pass affiliations: Indy Pass, Indy+ Pass – 2 daysClosest neighboring ski areas: Otsego (:07), Boyne Mountain (:34), Hanson Hills (:39), Shanty Creek (:51), The Highlands (:58), Nub’s Nob (1:00)Base elevation: 1,110 feetSummit elevation: 1,333 feetVertical drop: 223 feetSkiable acres: 80Average annual snowfall: 140 inchesTrail count: 25 (30% beginner, 40% intermediate, 30% advanced)Lift count: 5 (3 triples, 2 carpets – view Lift Blog’s inventory of Treetops’ lift fleet)Why I interviewed himThe first 10 ski areas I ever skied, in order, were:* Mott Mountain, Michigan* Apple Mountain, Michigan* Snow Snake, Michigan* Caberfae, Michigan* Crystal Mountain, Michigan* Nub’s Nob, Michigan* Skyline, Michigan* Treetops, Michigan* Sugar Loaf, Michigan* Shanty Creek – Schuss Mountain, MichiganAnd here are the first 10 ski areas I ever skied that are still open, with anything that didn’t make it crossed out:* Mott Mountain, Michigan* Apple Mountain, Michigan* Snow Snake, Michigan* Caberfae, Michigan* Crystal Mountain, Michigan* Nub’s Nob, Michigan* Skyline, Michigan* Treetops, Michigan* Sugar Loaf, Michigan* Shanty Creek – Schuss Mountain, Michigan* Shanty Creek – Summit, Michigan* Boyne Mountain, Michigan* Searchmont, Ontario* Nebraski, Nebraska* Copper Mountain, Colorado* Keystone, ColoradoSix of my first 16. Poof. That’s a failure rate of 37.5 percent. I’m no statistician, but I’d categorize that as “not good.”Now, there’s some nuance to this list. I skied all of these between 1992 and 1995. Most had faded officially or functionally by 2000, around the time that America’s Great Ski Area Die-Off concluded (Summit lasted until around Covid, and could still re-open, resort officials tell me). Their causes of death are varied, some combination, usually, of incompetence, indifference, and failure to adapt. To climate change, yes, but more of the cultural kind of adaptation than the environmental sort.The first dozen ski areas on this list are tightly bunched, geographically, in the upper half of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula. They draw from the same general population centers and suffer from the same stunted Midwest verticals. None are naturally or automatically great ski areas. None are or were particularly remote or tricky to access, and most sit alongside or near a major state or federal highway. And they (mostly) all benefit from the same Lake Michigan lake-effect snow machine, the output of which appears to be increasing as the Great Lakes freeze more slowly and less often (cold air flowing over warm water = lake-effect snow).Had you presented this list of a dozen Michigan ski areas to me in 1995 and said, “five of these will drop dead in the next 30 years,” I would not have chosen those five, necessarily, to fail. These weren’t ropetow backwaters. All but Apple had chairlifts (and they soon installed one), and most sat close to cities or were attached to a larger resort. Sugar Loaf, in particular, was one of Michigan’s better ski areas, with five chairlifts and the largest in-state vertical drop on this list.My guess for most-likely-to-die probably would have been Treetops, especially if you’d told me that then-private Otsego ski area, right next door and with twice its neighbor’s skiable acreage, vertical drop, and number of chairlifts, would eventually open to the public. Especially if you’d told me that Boyne Mountain, the monster down the road, would continue to expand its lodging and village, and would add a Treetops-sized cluster of greens to its ferocious ridge of blacks. Especially if you’d told me that Treetops’ trail footprint, never substantial, would remain more or less the same size 30 years later. In fact, just about every surviving Michigan ski area on that list - Crystal, Nub’s, Caberfae, Shanty Schuss - greatly expanded its terrain footprint. Except Treetops.But here we are, in the future, and I just skied Treetops 10 months ago with my 8-year-old son. It was, in some ways, more or less as I’d left it on my last visit, in 1995: small vert, small trail network, a slightly confusing parking situation, no chairlift restraint bars. A few improvements were obvious: the beginner ropetows had made way for a carpet, the last double chair had been upgraded to a triple, terrain park features dotted the east side, and a dozen or so glades and short steep shots had been hacked from the woods of the legacy trail footprint.That’s all nice. But what was not obvious to me was this: why, and how, does Treetops the ski area still exist? Sugar Loaf was a better ski area. Apple Mountain was closer to large population centers. Summit was attached to ski-in-ski-out accommodations and shared a lift ticket with the larger Schuss mountain a couple miles away. Was modern Treetops some sort of money-losing ski area hobby horse for whomever owned the larger resort, which is better known for its five golf courses? Was it just an amenity to keep the second homeowners who mostly lived in Southeast Michigan invested year-round? Had the ski area cemented itself as the kind of high-volume schoolkids training ground that explained the resilience of ski areas in metro Detroit, Minneapolis, and Milwaukee?There is never, or rarely, one easy or obvious explanation for why similar businesses thrive or fail. This is why I resist pinning the numerical decline in America’s ski area inventory solely to climate change. We may have fewer ski areas in America than we had in 1995, but we have a lot more good ski areas now than we did 30 years ago (and, as I wrote in March, a lot more overall ski terrain). Yes, Skyline, 40 minutes south of Treetops, failed because it never installed snowmaking, but that is only part of the sentence. Skyline failed because it never installed snowmaking while its competitors aggressively expanded and continually updated their snowmaking systems, raising the floor on the minimal ski experience acceptable to consumers. That takes us back to culture. What do you reckon has changed more over the past 30 to 40 years: America’s weather patterns, or its culture? For anyone who remembers ashtrays at McDonald’s or who rode in the bed of a pickup truck from Michigan to Illinois or who ran feral and unsupervised outdoors from toddlerhood or who somehow fumbled through this vast world without the internet or a Pet Rectangle or their evil offspring social media, the answer seems obvious. The weather feels a little different. Our culture feels airlifted from another planet. Americans accepted things 30 years ago that would seem outrageous today – like smoking adjacent to a children’s play area ornamented with a demented smiling clown. But this applies to skiing as well. My Treetops day in 1995 was memorably horrible, the snow groomed but fossilized, unturnable. A few weeks earlier, I’d skied Skyline on perhaps a three-inch base, grass poking through the trails. Modern skiers, armed with the internet and its Hubble connection to every ski area on the planet, would not accept either set of conditions today. But one of those ski areas adapted and the other did not. That’s the “why” of Treetops survival. It was the “how” that I needed Barry Owens to help me understand.What we talked aboutLast winter’s ice storm – “it provides great insight into human character when you go through that stuff”; record snowfall (204 inches!) to chase the worst winter ever; the Lake Michigan snowbelt; a golf resort with a ski area attached; building a ski culture when “we didn’t have enough people dedicated to ski… and it showed”; competing with nearby ski areas many times Treetops’ size “we don’t shy away from… who we are and what we are”; what happened when next-door-neighbor Otsego Resort switched from a private to a public model in 2017 – “neither one of us is going to get rich seeing who can get the most $15 lift tickets on a Wednesday”; I attempt to talk about golf and why Michigan is a golf mecca; moving on from something you’ve spent decades building; Treetops’ rough financial period and why Owens initially turned down the GM job; how Owens convinced ownership not to close the ski area; fixing a “can’t-do staff” by “doing things that created the freedom to be able to act”; Treetops’ strange 2014 bankruptcy and rebuilding from there; “right now we’re happy” with the lift fleet; how much it would cost to retrofit Treetops’ lifts with restraint bars; timeline for potential ski expansion at Treetops; bargain season passes (as low as $125); and Indy Pass’ network power.What I got wrong* I said “Gaylord County,” but the city of Gaylord is in Otsego County.* I said that Boyne Resorts, operator of 11 ski areas, also runs “10 or 11 golf resorts.” The company operates 14 golf courses.* I said that Michigan had a “very good” road network and that there was “not a lot of traffic,” and if you live there, you’re reaction is probably, “you’re dumb.” What I meant by “very good road network” is this: compared to most ski regions, which have, um, mountains, Michigan’s bumplets sit more or less directly alongside the state’s straight, flat, almost perfectly gridded highway network. Also, the “not a lot of traffic” thing does not apply to special situations like, say, northbound I-75 on a July Friday evening.* I said that Crystal, Nub’s, Caberfae, and Shanty Creek were “close” – while they’re not necessarily all close to one another, they are all roughly equidistant for folks coming to them from downstate.* I said that Treetops was “the fifth or sixth place I ever skied at,” but upon further review, it was number eight (which is reflected in the list above).Podcast NotesOn the ice stormAn ice storm hammered Northern Michigan in late March of this year:On the lightning strike on Treetops’ golf courseOn the Midwest’s terrible 2023-24 ski seasonSkier visits c

Take 20% off a paid annual ‘Storm’ subscription through Monday, Oct. 27, 2025.WhoJared Smith, Chief Executive Officer of Alterra Mountain CompanyRecorded onOctober 22, 2025About Alterra Mountain CompanyAlterra is skiing’s Voltron, a collection of super-bots united to form one super-duper bot. Only instead of gigantic robot lions the bots are gigantic ski areas and instead of fighting the evil King Zarkon they combined to battle Vail Resorts and its cackling mad Epic Pass. Here is Alterra’s current ski-bot stable:Alterra of course also owns the Ikon Pass, which for the 2025-26 winter gives skiers all of this:Ikon launched in 2018 as a more-or-less-even competitor to Epic Pass, both in number and stature of ski areas and price, but long ago blew past its mass-market competitor in both:Those 89 total ski areas include nine that Alterra added last week in Japan, South Korea, and China. Some of these 89 partners, however, are so-called “bonus mountains,” which are Alterra’s Cinderellas. And not Cinderella at the end of the story when she rules the kingdom and dines on stag and hunts peasants for sport but first-scene Cinderella when she lives in a windowless tower and wears a burlap dress and her only friends are talking mice. Meaning skiers can use their Ikon Pass to ski at these places but they are not I repeat NOT on the Ikon Pass so don’t you dare say they are (they are).While the Ikon Pass is Alterra’s Excalibur, many of its owned mountains offer their own season passes (see Alterra chart above). And many now offer their own SUPER-DUPER season passes that let skiers do things like cut in front of the poors and dine on stag in private lounges:These SUPER-DUPER passes don’t bother me though a lot of you want me to say they’re THE END OF SKIING. I won’t put a lot of effort into talking you off that point so long as you’re all skiing for $17 per day on your Ikon Passes. But I will continue to puzzle over why the Ikon Session Pass is such a very very bad and terrible product compared to every other day pass including those sold by Alterra’s own mountains. I am also not a big advocate for peak-day lift ticket prices that resemble those of black-market hand sanitizer in March 2020:Fortunately Vail and Alterra seem to have launched a lift ticket price war, the first battle of which is The Battle of Give Half Off Coupons to Your Dumb Friends Who Don’t Buy A Ski Pass 10 Months Before They Plan to Ski:Alterra also runs some heli-ski outfits up in B.C. but I’m not going to bother decoding all that because one reason I started The Storm was because I was over stories of Bros skiing 45 feet of powder at the top of the Chugach while the rest of us fretted over parking reservations and the $5 replacement cost of an RFID card. I know some of you are like Bro how many stories do you think the world needs about chairlifts but hey at least pretty much anyone reading this can go ride them.Oh and also I probably lost like 95 percent of you with Voltron because unless you were between the ages of 7 and 8 in the mid-1980s you probably missed this:One neat thing about skiing is that if someone ran headfirst into a snowgun in 1985 and spent four decades in a coma and woke up tomorrow they’d still know pretty much all the ski areas even if they were confused about what’s a Palisades Tahoe and why all of us future wussies wear helmets. “Damn it, Son in my day we didn’t bother and I’m just fine. Now grab $20 and a pack of smokes and let’s go skiing.”Why I interviewed himFor pretty much the same reason I interviewed this fellow:I mean like it or not these two companies dominate modern lift-served skiing in this country, at least from a narrative point of view. And while I do everything I can to demonstrate that between the Indy Pass and ski areas not in Colorado or Utah or Tahoe plenty of skier choice remains, it’s impossible to ignore the fact that Alterra’s 17 U.S. ski areas and Vail’s 36 together make up around 30 percent of the skiable terrain across America’s 509 active ski areas:And man when you add in all U.S. Epic and Ikon mountains it’s like dang:We know publicly traded Vail’s Epic Pass sales numbers and we know those numbers have softened over the past couple of years, but we don’t have similar access to Alterra’s numbers. A source with direct knowledge of Ikon Pass sales recently told me that unit sales had increased every year. Perhaps some day someone will anonymously message me a screenshot code-named Alterra’s Big Dumb Chart documenting unit and dollar sales since Ikon’s 2018 launch. In the meantime, I’m just going to have to keep talking to the guy running the company and asking extremely sly questions like, “if you had to give us a ballpark estimate of exactly how many Ikon Passes you sold and how much you paid each partner mountain and which ski area you’re going to buy next, what would you say?”What we talked aboutA first-to-open competition between A-Basin and Winter Park (A-Basin won); the allure of skiing Japan; Ikon as first-to-market in South Korea and China; continued Ikon expansion in Europe; who’s buying Ikon?; bonus mountains; half-off friends tickets; reserve passes; “one of the things we’ve struggled with as an industry are the dynamics between purchasing a pass and the daily lift ticket price”; “we’ve got to find ways to make it more accessible, more affordable, more often for more people”; Europe as a cheaper ski alternative to the West; “we are focused every day on … what is the right price for the right consumer on the right day?”; “there’s never been more innovation” in the ski ticket space; Palisades Tahoe’s 14-year-village-expansion approval saga; America’s “increasingly complex” landscape of community stakeholders; and Deer Valley’s massive expansion.What I got wrong* We didn’t get this wrong, but when we recorded this pod on Wednesday, Smith and I discussed which of Alterra’s ski areas would open first. Arapahoe Basin won that fight, opening today (Sunday, Oct. 26).* I said that 40 percent of all Epic, Ikon, and Indy pass partners were outside of North America. This is inaccurate: 40 percent (152) of those three passes’ combined 383 partners is outside the United States. Subtracting their 49 Canadian ski areas gives us 103 mountains outside of North America, or 27 percent of the total.* I claimed that a ski vacation to Europe is “a quarter of the price” of a similar trip to the U.S. This was hyperbole, and obviously the available price range of ski vacations is enormous, but in general, prices for everything from lift tickets to hotels to food tend to be lower in the Alps than in the Rocky Mountain core.* It probably seems strange that I said that Deer Valley’s East Village was great because you could drive there from the airport without hitting a spotlight and also said that the resort would be less car-dependent. What I meant by that was that once you arrive at East Village, it is – or will be, when complete – a better slopeside pedestrian village experience than the car-oriented Snow Park that has long served as the resort’s principal entry point. Snow Park itself is scheduled to evolve from parking-lot-and-nothing-else to secondary pedestrian village. The final version of Deer Valley should reduce the number of cars within Park City proper and create a more vibrant atmosphere at the ski area.Questions I wish I’d askedThe first question you’re probably asking is “Bro why is this so short aren’t your podcasts usually longer than a Superfund cleanup?” Well I take what I can get and if there’s a question you can think of related to Ikon or Alterra or any of the company’s mountains, it was on my list. But Smith had either 30 minutes or zero minutes so I took the win.Podcast NotesOn Deer ValleyI was talking to the Deer Valley folks the other day and we agreed that they’re doing so much so fast that it’s almost impossible to tell the story. I mean this was Deer Valley two winters ago:And this will be Deer Valley this winter:Somehow it’s easier to write 3,000 words on Indy Pass adding a couple of Northeast backwaters than it is to frame up the ambitions of a Utah ski area expanding by as much skiable acreage as all 30 New Hampshire ski areas combined in just two years. Anyway Deer Valley is about to be the sixth-largest ski area in America and when this whole project is done in a few years it will be number four at 5,700 acres, behind only Vail Resorts’ neighboring Park City (7,300 acres), Alterra’s own Palisades Tahoe (6,000 acres), and Boyne Resorts’ Big Sky (5,850 acres).On recent Steamboat upgradesYes the Wild Blue Gondola is cool and I’m sure everyone from Baton-Tucky just loves it. But everything I’m hearing out of Steamboat over the past couple of winters indicates that A) the 650-acre Mahogany Ridge expansion adds a fistfighting dimension to what had largely been an intermediate ski resort, and that, B) so far, no one goes over there, partially because they don’t know about it and partially because the resort only cut one trail in the whole amazing zone (far looker’s left):I guess just go ski this one while everyone else still thinks Steamboat is nothing but gondolas and Sunshine Peak.On Winter Park being “on deck”After stringing the two sides of Palisades Tahoe together with a $75 trillion gondola and expanding Steamboat and nearly tripling the size of Deer Valley, all signs point to Alterra next pushing its resources into actualizing Winter Park’s ambitious masterplan, starting with the gondola connection to town (right side of map):On new Ikon Pass partners for 2025-26You can read about the bonus partners above, but here are the write-ups on Ikon’s full seven/five-day partners:On previous Alterra podcastsThis was Smith’s second appearance on the pod. Here’s number one, from 2023:His predecessor, Rusty Gregory, appeared on the show three times:I’ve also hosted the leaders of a bunch of Alterra leaders on the pod, most recently A-Basin and Mammoth:And the heads of many Ikon Pass partners – most