98. At the Panama Canal Museum, Ana Elizabeth González Creates a Global Connection Point

Description

When Ana Elizabeth González was growing up in Panama, the history she learned about the Panama Canal in school told a narrow story about the engineering feat of the Canal’s construction by the United States. This public history reflected the politics of Panama and control over the Canal.

Today, González is executive Director of the Panama Canal Museum, and she’s determined to use the Canal and the struggles over its authority to tell a broader story about the history of Panama – one centered around Panama as a point of connection from pre-Colonial times to the present day.

In this episode, González describes the geographic destiny of the Isthmus of Panama, how America’s ownership of the Canal physically divided the country, and how her team is developing galleries covering Panama’s recent history.

Topics and Notes

- 00:00 Intro

- 00:15 The Panama Canal's Politically Sensitive History

- 01:20 Ana Elizabeth González, Executive Director of the Panama Canal Museum

- 01:35 Opening of the Panama Canal Museum in 1997

- 02:44 Making the Museum About Panama, Not Just The Canal

- 03:10 Geography is Destiny

- 03:30 The Isthmus of Panama as a Point of Connection

- 04:20 A Brief History

- 04:50 French Attempt at a Canal

- 05:10 Treaty of Hay–Bunau-Varilla

- 06:30 Construction of the Canal

- 07:00 "Gold Roll" and "Silver Roll"

- 08:00 Martyrs' Day

- 08:50 Work In Progress: Galleries of Panama's Recent History

- 09:10 Panama's Recent History, Briefly

- 11:10 The Museum's Future

- 11:15 Museum Archipelago's 100th Episode Party 🎉

- 12:20 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖

Museum Archipelago is a tiny show guiding you through the rocky landscape of museums. Subscribe to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, or even email to never miss an episode.

Support Museum Archipelago🏖️

- Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don’t make it into the main show;

- Archipelago at the Movies 🎟️, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies that take place at museums;

- Logo stickers, pins and other extras, mailed straight to your door;

- A warm feeling knowing you’re supporting the podcast.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 98. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

<input id="collapsible" class="toggle" type="checkbox">

<label for="collapsible" class="lbl-toggle">View Transcript</label>

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsner. Museum Archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is never longer than 15 minutes, so let's get started.

When Ana Elizabeth González was growing up in Panama, the history she learned in school about the Panama Canal told a narrow story.

Ana Elizabeth González: The history of the canal that was told here was told in a way that was very politically sensitive at the time. So it didn't want to ruffle any feathers.. it's mentioned in schools, but not in depth.

Up until 1979, the United States fully controlled the Panama Canal and a 5 mile zone on either side, and until 1999, the United States jointly controlled the Canal with Panama. The presence of the United States, and the politics of the Canal, meant that the safest story to tell was one that was mostly focused on the technological feat of building it.

Ana Elizabeth González: The history was very carefully constructed so that it praised the engineering feat of the United States, but it completely ignored the fact that Panama was home to people from 97 different countries to build this Canal, which causes such a diversity in our country.

Ana Elizabeth González is now Executive director of the Panama Canal Museum in Panama City, Panama.

Ana Elizabeth: Hello. My name is Ana Elizabeth González and I'm executive director of the Panama canal museum, El Museo Del Canal.

González became director in 2020, but the Panama Canal Museum itself opened in 1997, two years before control of the Canal was returned to Panama. The museum – a non-profit which is not government funded – was created out of a hope that, among all the changes, Pamana’s complex relationship to the Canal would not be forgotten.

Ana Elizabeth González: I was in school at the time, but, I remember it was, I think the then President of Panama and the Mayor and a lot of other people that created the board of trustees and I think it was the idea that this history of this struggle to gain our land and to find our sovereignty and the generational struggle that had been going on. There was a fear that it would have gotten lost in memory or forgotten. So I think that the museum back then was created to preserve and study and research everything surrounding the Canal history and promoting the education of what an impact it had.

So for González, the Panama Canal Museum is really a museum about Panama.

Ana Elizabeth González: I think people come with the preconception that the museum is just going to be about how the Canal works and how the locks open fill with water. And we don't really have that in-depth here. That's why the Canal has a visitor center that explains how it works in terms of technology and engineering. But it's something we just brush over here because we deep dive into the history of Panama as a point of connection. And as this route that changed the world.

The first gallery of the museum begins long before the Canal and highlights the unique features of Panama’s geography: a small isthmus that’s both the only way to travel between the North and South American continents by land and also the narrowest land between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Ana Elizabeth González: We've been a trade route or over a route of connection. Ever since Panama – well, the territory sort of resurfaced from, from the oceans, because we were always a bridge between north and south America for animal species and then indigenous peoples. So we've always sort of been a point of trade and contact both culturally and commercially. You enter, the first exhibition space, which is the sort of emergence of Panama as a land in this sort of Omni globe that we have, and you see how it connects both landmasses of North and South America. And you go through the exhibition towards the pre-colonial living traditions, and what Panama was like before the Spanish colonization, then the importance of Panama as part of the Spanish crown and monarchy until 1821.

After three hundred years as part of the Spanish monarchy, the isthmus’s geography started to look even more useful to outside interests during the 19th century, as global trade started to pick up. Here, goods and passengers could bypass a much longer and much more dangerous journey around the Strait of Magellan on the southern tip of South America. In 1855, a railway was built across the Isthmus, facilitating the movement of people and goods in time for a wave of the California gold rush.

Ana Elizabeth González: And then in 1881, if I'm correct, the French after the success of the Suez Canal, the French chose to build a canal through Panama. Unfortunately, due to yellow fever and other diseases and badly managed funds, the enterprise did not succeed, but it was bought from the French by the United States through the treaty of, Hay–Bunau-Varilla, which we signed upon getting our independence as a country.

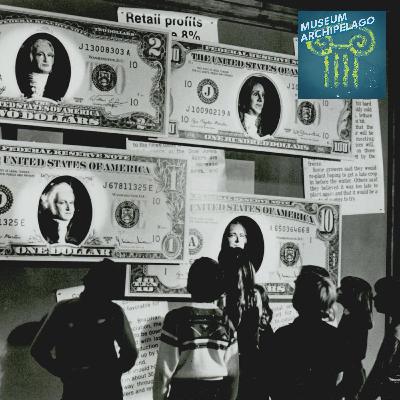

The 1903 treaty of Hay–Bunau-Varilla granted the United States complete ownership over a 50 mile long slice of land that was to be the Canal. In the gallery, visitors walk through a hallway that’s completely covered in words from that treaty. Powerful words like “perpetuity” and “authority” look down on them.

Ana Elizabeth González: The United States had rights for… well for forever it wasn't even a question of whether or not they owned it. They owned the land where it was going to be built and the land where they had to opera