Are Tariffs a Government Theft of your Property?

Description

Tariffs will certainly raise prices at home. That’s their purpose. Tariffs are taxes. When a product crosses the border, a tariff adds a fee. The item is the same, the seller worked no harder, but government tilted the scale to favor domestic goods.

So here’s the real question. If the state forces you to pay more than the market demands, and the extra money flows to a private pocket and not to a public good, is that a government theft of your property? It’s not as black and white as saying yes.

Trade Walls and the Great Collapse

(Background: somber string swell. An overture to a tragedy.)

In 1929 America walked to the cliff’s edge. On the day historians now call Black Monday, October 28, the stock market plunged 13 percent. The next day, it fell another 12. And the slide continued.

By mid‑November the market had surrendered half its value. But this was no abstract loss for wealthy speculators. Credit froze. Banks failed. Capital vanished.

The drop tore through real people’s lives. Factories emptied, foreclosures surged, crime climbed. City tax bases collapsed; boarded windows lined dark streets.

In manufacturing-heavy cities like Detroit and Chicago, unemployment reached 40 percent. On the plains, farmers who had expanded acreage during World War I and loaded themselves with debt to feed Allied armies now could not sell grain for the cost of planting it. Some burned corn for heat because coal was more expensive. Families lived in makeshift shacks made from scrap wood and tar paper.

The shock ran so deep it took twenty-five years and twenty-five days, an entire generation, to recover. Only on November 23, 1954, did the Dow Jones Industrial Average climb back to its 1929 peak.

It took the Second World War, an immense post‑war industrial boom, and the rise of a broad middle class to erase the wounds opened in those brutal weeks of 1929.

…

But in 1929, the nation was still reeling.

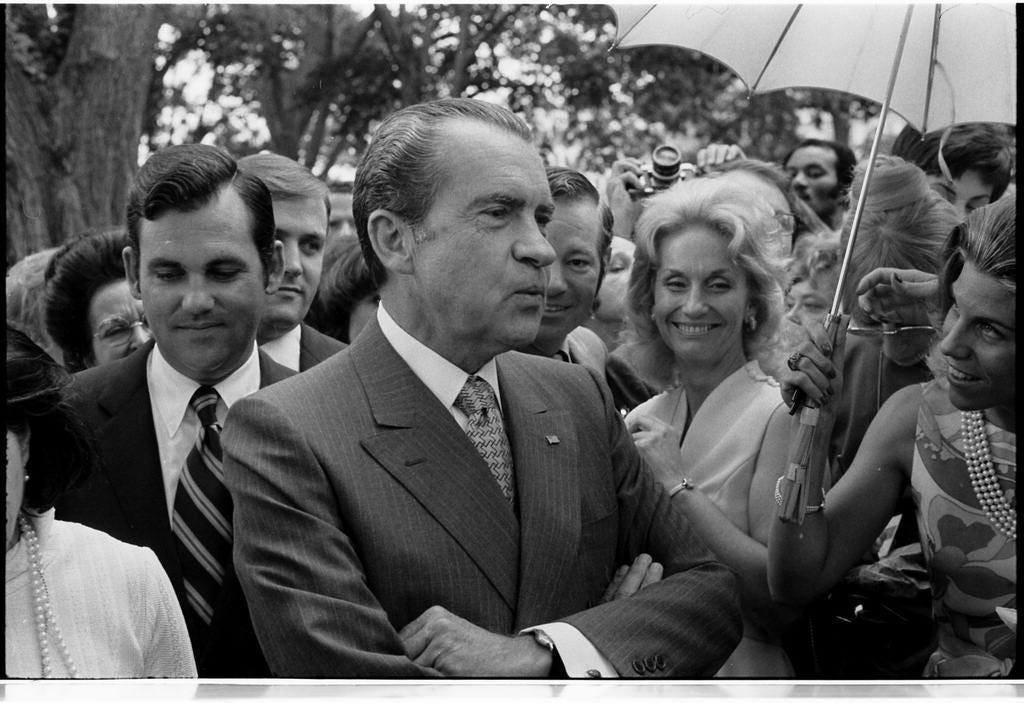

Into that chaos stepped two well-meaning legislators: Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Congressman Willis Hawley of Oregon. Smoot chaired the Senate Finance Committee. Hawley led the House Ways and Means Committee. Both were Republicans. Their fix looked simple on paper. They intended to raise tariffs and shield American jobs, especially in struggling farms and factories.

Tariffs were nothing new. All through the nineteenth century they filled the federal treasury and sheltered northern mills before an income tax even existed.

But by 1930, the economy was global. Exports mattered. War‑debtor Europe owed the United States billions, and America needed foreign buyers to keep those payments flowing. The system was fragile, stretched by World War I debts and sliding prices.

This fragile system was about to get kicked in the teeth.

Smoot and Hawley introduced their bill in 1929 as a narrow farm measure. Washington lobbyists smelled opportunity. Amendments poured in. Every senator, every representative, tacked on protection for home‑state industries. The schedule exploded.

Tariffs climbed on more than twenty thousand imports, including shoes, lumber, eggs, cement, even musical instruments.

[Sound cue: typewriters clacking rapidly, fading into thunder]

Over a thousand economists signed a letter urging President Hoover to veto it. They warned it would spark retaliation and crush trade.

Hoover, boxed in by party pressure and a panicked electorate, signed the Smoot‑Hawley Tariff Act into law on June 17, 1930.

…

That’s when the backlash began.

Canada struck first, taxing American wheat and produce. Europe followed. Germany, France, Britain. The global economy was already fragile. Retaliation sent it into a spiral. Within a few years world trade fell more than sixty percent. American exports were cut in half. Factories shut their gates. Jobs vanished. Farms that hoped for relief found only isolation.

[Background: wind blowing through an empty field]

Unemployment soared past 20 percent. Dust storms rolled across the heartland.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act didn’t cause the Great Depression. But it poured gasoline on the fire. It bruised American credibility and hardened global resentment.

The lesson came fast and harsh: Economic nationalism backfires in a global crisis. Economists still cite the Smoot-Hawley Act as proof that fear-driven policy can deepen disaster .

Voters felt the pain. In the 1930 midterms, Republicans lost both chambers of Congress by huge margins. Smoot and Hawley were “shown the door.”

Even progressive Republicans who had campaigned for Hoover switched sides and backed Democrat Franklin Roosevelt in 1932. By his inauguration on March 4, 1933, banks were closing, unemployment hovered near twenty-five percent, and prices and productivity had fallen to one-third of their 1929 level .

We now know FDR would lead the country through the Great Depression and to victory in World War II. He would go on to win four consecutive presidential campaigns. It would take 20 years and a war hero named Dwight Eisenhower for the Republicans to win the presidency again.

Decades later, economists point to the Smoot-Hawley Act as the moment protectionism went too far.

What are Tariffs?

A tariff is a border tax. Each time a shipment enters the United States, from raw materials to cars, the US importer pays the tariff before the goods clear customs. That cost travels through the supply chain until it lands in the shopper’s cart.

The Constitution calls such a fee an impost and grants only Congress the power to levy it.

In the early Republic, tariffs kept the government running. We only had to pay for a small army, a handful of diplomats, and debt payments. Customs duties and land sales covered it all. No income tax. No redistribution. In that setting, tariffs were neutral revenue.

Today, they play a different role. Lawmakers use them to shield selected industries. The higher price never builds a road or pays the debt. It settles in the profit line of the firm that now faces less competition.

As a buyer, you pay more, without consent, to subsidize a private interest. The protected company can hold prices high and still move product. That extra margin is private gain created by government design.

So the question stands.

If the state makes you pay more than the market asks and the surplus flows to a private pocket, are tariffs a government theft of your property?

Are Tariffs a Government Theft of Your Property?

Let’s look first through the lens of the individual and their natural rights.

The decisive purpose of governance is to preserve your life, liberty, and estate.

Life is your own being. It includes every decision that keeps you alive and whole. By nature, you own yourself.

Liberty is the right to choose a path that leads to fulfillment. When we chart our own course, we observe, plan, and act. Our choices bring results, good or bad, and from those results we develop skill, talent, and personal responsibility. What we do matters, but who we become by doing it matters more.

Estate is the concrete result of that pursuit of happiness. It is your paycheck, the land you work, your tools, the food on your table, the heat in your house. It is everything earned by your labor and freely exchanged with others.

We consent to governance so our representatives can preserve those rights.

When government collects taxes to keep the peace, enforce contracts, and build institutions that enable Americans born in trailers and penthouses alike to be great, it strengthens the pillars. When it shifts wealth from many citizens to a favored few, it weakens them.

The Constitution reflects that balance. Article I empowers Congress to collect tariffs to promote the general welfare. <a href