Does the Civil Rights Act Violate the Constitution?

Description

On September 10th, a gunman killed Charlie Kirk in Utah. The event reminds us that no one should die over speech, and that we must wrestle with big questions calmly. You don’t have to love him or hate him. At times, his message resonated with many across America. At times, it divided us. If we say we disagree with his points, we should be able to make the case. If we can’t, his spears carry weight.

One of his sharpest questions was this: Does the Civil Rights Act of 1964 violate the Constitution?

Let’s sit with that for a moment. If your first thought is, “That law ended Jim Crow. How could it be wrong?” you’re not alone. We wrote the law to strike down a national disgrace. To end segregation. To stop the humiliation of being turned away from a lunch counter, of being told you couldn’t buy a home in a certain neighborhood, of being trapped in second-class status.

We intended the Civil Rights Act to end those humiliations. To tear down the walls of segregation. To give every American a fair shot.

In that moment, justice demanded action.

But justice isn’t just a word. It’s a goal that shapes real lives. It’s the chance for a kid who grows up in a leaky trailer or in project housing to work, to save, and to buy a house in a neighborhood where their children have a good school and a fair shot. From a word on a page to life on the ground.

According to the Constitution’s chief authors, justice may be the most important of the six national goals that bind our Republic.

But justice isn’t a handout program. Justice is the chance to earn your place. It’s not a promise of results. Because the goals in our preamble, meaning union, liberty, welfare, defence, order, and justice, sometimes compete or clash, we must hold them in balance.

In the end, our goal isn’t to win an argument. It’s to get better, together, at pursuing the ideals that bind us.

So here’s the question: in the balance between Union, Liberty, and Justice, does the Civil Rights Act of 1964 violate the Constitution?

Act One. A Plate of Segregation

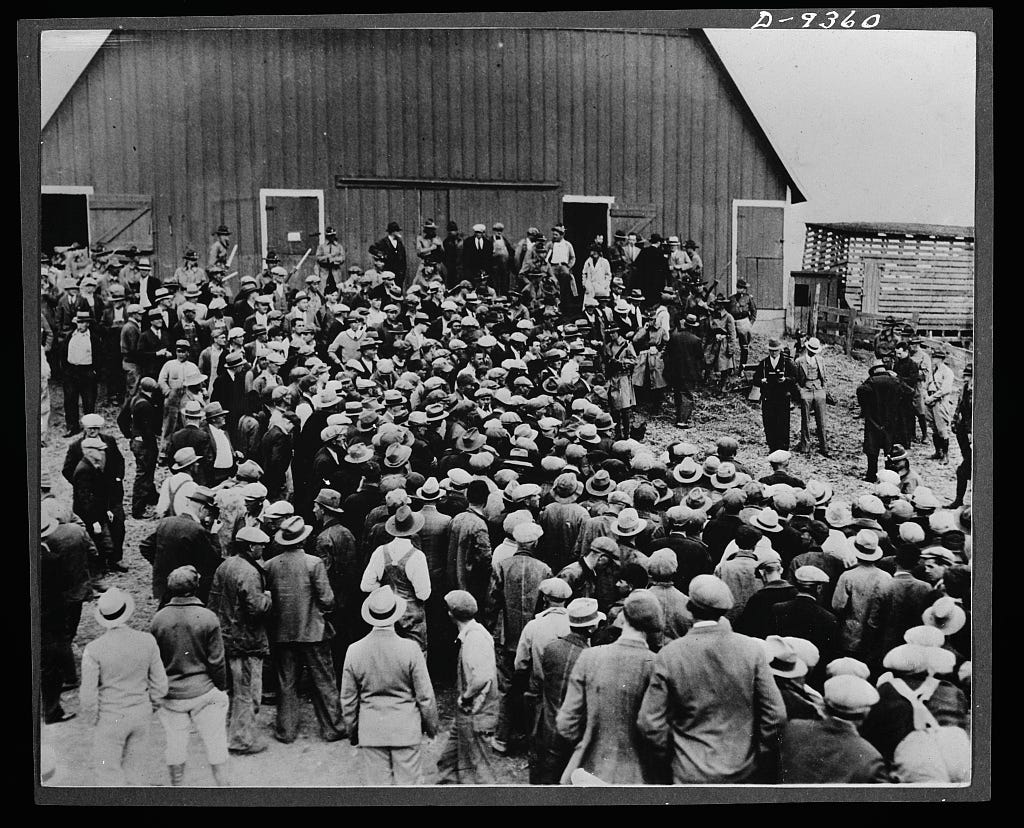

In the mid-1960s, Maurice Bessinger’s Piggie Park barbecue ran popular drive-ins and a sit-down sandwich shop around Columbia, South Carolina. The chain routinely denied Black customers full and equal service. Those who were served had to take food at kitchen windows and were not allowed to eat on the premises.

After Congress approved the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title II barred restaurants and other public accommodations from excluding people by race. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed it on July 2, 1964, in a nationally televised ceremony attended by lawmakers and civil-rights leaders, among them Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Had equality arrived?

Not everywhere. Piggie Park didn’t change. On July 3, Anne Newman, a mother and minister’s wife, wanted a sandwich. Instead, she got a full plate of rejection. She and her friends went to Piggie Park for lunch. The waitress came out, saw she and her friends were Black, and turned back inside without taking the order.

They went back a month later and were again refused service.

The moment sparked a fight for justice. Newman, Sharon Neal, and John Mungin filed a class action suit seeking an injunction to stop the discrimination at the restaurants.

This wasn’t a casual “we can agree to disagree” dispute. Bessinger stocked his restaurants with booklets defending racial separation. You could pick up this reading with your barbecue. It drew on the Genesis 11 story of the Tower of Babel to argue that God scattered the nations and meant them to remain separate. Integration, he preached, defied divine order. Some pamphlets even claimed biblical warrant for slavery.

At first, the courts split. They wrestled with how far the law reached. The district court agreed that there had been discrimination. They also ruled that drive-ins, where most food was takeout, didn’t have to follow the law. The Fourth Circuit disagreed, saying all Piggie Park locations were public accommodations.

Newman v. Piggie Park went to the Supreme Court in 1968. The high court sided with Newman and made it plain: religion is no excuse for segregation in a public restaurant. The justices called Piggie Park’s claim “patently frivolous.”

Piggie Park wasn’t about handouts or special favors. It was about human dignity. The right to walk into a public restaurant and be served like anyone else. Believe what you want. But if you open your doors to the public, you serve the public.

So…did the Civil Rights Act of 1964 violate the Constitution in Columbia, South Carolina?

Did the decision rob Maurice Bessinger of his religious liberty? He was still free to believe, worship, preach, and pass out booklets. What he couldn’t do after choosing to run a public restaurant was use those beliefs to keep people out.

And he didn’t stop speaking his mind. Before he died, he deeded a tiny patch of ground under the flagpole to the Sons of Confederate Veterans for five dollars so that future owners couldn’t take the Confederate flag down.

But the issue isn’t cut and dry. The stories don’t stop in South Carolina.

Act Two. A Seat With Conditions

In the late 1960s, the University of California, Davis School of Medicine faced a stark reality: its classes had almost no Black, Latino, or Native American students. Justice is the opportunity to earn a place, but what does opportunity mean when the doorway to a profession has been locked for decades?

UC Davis tried a fix: Out of 100 seats each year, they reserved 16 for “disadvantaged” applicants. UC Davis judged those applications by a separate committee, with different standards, and the underrepresented minority applicants competed only for those 16 seats.

Enter Allan Bakke. A Marine Corps veteran and engineer in his early 30s, Bakke had set his sights on medicine. He’d spent years preparing, earning strong grades and MCAT scores. He applied to UC Davis in 1973 and 1974, along with a dozen other medical schools, and he was rejected by all of them. Later, he discovered that some minority applicants admitted through the special program had lower scores.

He believed the school had shut him out because he was white. In reality, records later showed that competition was stiff; as many as 67 applicants had higher scores than his.

Nonetheless, Bakke sued. He argued that a publicly-funded state school couldn’t deny him a seat and still honor the commitment to prohibit race discrimination in federally funded programs.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke reached the Supreme Court in 1978. The ruling was messy. Quotas, like the 16 reserved seats, were unconstitutional. They could not exclude Bakke based on race. The court ordered him admitted.

But the Court, led by Justice Lewis Powell, also said diversity in education is a compelling goal. Race could be one factor in a holistic review, as long as every applicant competes in the same pool, with no guaranteed quotas.

So…Did the enforcement of the Civil Rights Act violate the Constitution? Did it violate Bakke’s right to justice?

UC Davis had its opinion of justice. It argued that set-aside wasn’t favoritism. It was a correction for a pipeline bent by decades of exclusion. A diverse medical class would better serve California’s diverse communities.

If you were Bakke, would you see justice denied?

If you were a minority applicant, would you see the set-aside necessary to level a field tilted by history?

The Court decided justice meant the opportunity to compete equally, but not a scripted outcome. There could be no reserved seats, no separate tracks. But a school could consider race as one thread in a larger fabric, if every candidate competed equally.

Bakke went on to have a successful career as a doctor in Minnesota.

But the issue still isn’t settled. Let’s move on to Louisiana.

Act Three. From the Classroom to the Shop Floor

In 1965, President Johnson signed Executive Order 11246. In it, Johnson outlined that if a business wanted to compete for federal contracts, it had to follow the rules. If you wanted to do business with the federal government, you had to take “af