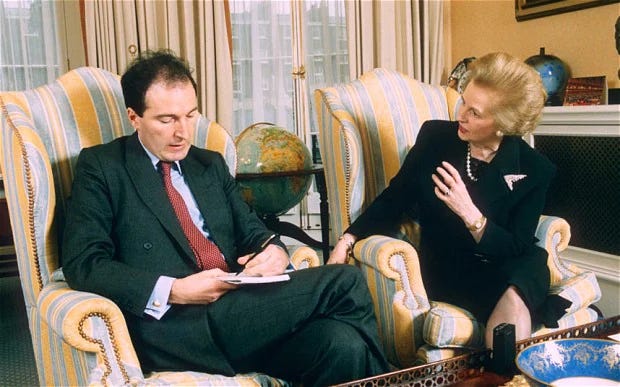

Charles Moore interview

Description

I was very pleased to talk to Charles Moore, who I have read admiringly for many years. His three volume biography of Margaret Thatcher is one of the most interesting biographies published in the last few years. He also edited a volume of T.E.Utley’s journalism. In this discussion you will hear (or read the transcript below!) whether Margaret Thatcher is more left-wing than we think, what Charles thinks of political biography, how his footnotes work, who are the most underrated Thatcher cabinet ministers, the relationship between fiction and biography, why he’s not a natural Thatcherite, and more. I asked a lot of my questions much less elegantly than I had written them, but the answers are frequently models of spoken English. I particularly enjoyed Charles’ use of “jealous” in its original, perhaps now semi-archaic, meaning (i.e. suspiciously vigilant or careful). He also seems to use “cunning” in the way Johnson defined it, pleasingly. I remember reading once how much Charles enjoyed the language of the Book of Common Prayer as a child. Perhaps those lexicographical waters run deep. The transcript is lightly edited for intelligibility. You will notice, sometimes, that the transcript moves from past to present tense when Charles talks about Margaret Thatcher. Here, as elsewhere, he often refers to her in the present tense. One topic we didn’t cover was Margaret Thatcher as a late bloomer. Maybe another time.

Henry: You once wrote that you found political biography boring to read, or you used to. Why did you find it interesting to write?

Charles Moore: I think making one's own enquiries makes you think about it more deeply, which is intrinsically interesting. But also I think the subject, Mrs. Thatcher, is a particularly interesting person because she was very unusual and because she was the first and, effectively at the time, only woman. And so everything's different. And so the impact of her is very strikingly different from that of even very well-known male politicians.

Henry: And do you enjoy reading political biography more now that you've written your book?

Charles Moore: I don't find that I do read it more, particularly. But probably the answer's yes because I can understand more how the work is done. And therefore, I can see who's good at it and who isn't, and when they're evading a subject they don't understand or whether they've really got to the bottom of it and so on.

Henry: How do you assess that? What sort of things make you think that someone's really got a grip on what they're telling you?

Charles Moore: Partly it's their mastery of the sources, of course. And also, it's a matter of, to some extent, perceiving their fairness. And I think that's quite an interesting subject, because fairness doesn't mean, necessarily, that you're neutral about the person. You can be highly sympathetic to the subject, or you can be even unsympathetic to the subject and still be fair. But fairness is something about considering the evidence and trying to give it its right weight. This, I think, is easily detectable in biographies. And some just don't do that. They wish to assassinate the character, or they wish to make a hero of the character, or they're simply rather lazy. If you've walked down that path, you can detect what's going on.

Henry: What parts of Margaret Thatcher's life did you find it most difficult to be fair about?

Charles Moore: Well of course, I wouldn't be the best judge of that, I suppose.

Henry: Were there any bits, though, where you had to work at that practise of fairness?

Charles Moore: One way in which you need to be fair to a subject is simply to try to understand the subject. I don't mean the biographical subject. I mean the issue. And there are certain subjects that I'm less good at and, therefore, have to work harder on like, let's say, monetary policy or details about missiles. Neither of which are my natural territory, and both of which are important in the case of Mrs. Thatcher. So I would have to make more efforts about that, mental efforts, to really understand what's going on than I would about, say, fighting an election or reform of the trade unions or something like that. There's a sort of broad point about being fair, which is that biography naturally and inevitably and rightly must focus on the individual. And therefore, it may do that to the exclusion of other individuals or of a wider milieu, which is an inevitable danger but is also a mistake because the individual in politics doesn't act alone, even a very remarkable character like Margaret Thatcher or Winston Churchill. And one needs, somehow, to convey the milieu and the weight of the other characters while never ceasing to focus on the one character.

One of the extraordinary features of Hilary Mantel's novels about Thomas Cromwell — Wolf Hall etc — is that, I think it's right to say, he is in the room the entire time, or in the field or whatever. I think Thomas Cromwell is in every scene. Sometimes it's reported speech that he's hearing, but still. And, as a biographer one sort of does that. Mrs. Thatcher is almost always in the room, not absolutely always. And that's right. That's fine. But one mustn't let her crowd everything else out.

Henry: Were the Mantel books a conscious model or influence for you, or is that something you've noticed separately?

Charles Moore: Not really because I was reading them more towards the end. Well, I read Wolf Hall quite a long time ago, and then I read the other two pretty much when I was finishing. But I think they're very good. Obviously, they're not biographies. But I think, I hope, I learnt something from them because there's a sustained effort of the imagination, which the novelist has to have, to see through the eyes of, in her case, Thomas Cromwell. And though biography is fact not fiction, imagination is required in biography as well. And so in some ways, it's a similar task.

Henry: On this question of the milieu that Margaret Thatcher was in, you paid a lot of attention in the three books to the biographies of all the people around her, especially in footnotes, but also when you're describing events such as the leadership election in 1990, there's a lot of biographic information. Is this compilation of brief lives, a way of providing not just information, but commentary, almost like a sort of prosopographia? What stood out to me was that, even just through the footnotes, it really details the way that she was very, very different to everyone else in that world, demographically and socially.

Charles Moore: Yes. That's right. So, in putting footnoted autobiographies of most of the characters, that's useful for reference, but it's also a sort of short-hand way of telling you about the milieu and the range of characters she was dealing with, and of course, it brings out the fact that they're almost all male and a very high percentage of them went to public schools and Oxford or Cambridge. She of course went to Oxford, but she didn't go to public school and she wasn't a man. So I think when your eye goes to bottom of the page and picks up one of those biographies, it should be helpful in its own right, but it also should have a cumulative effect of placing Mrs. Thatcher among all of these people and of course, rather like the only woman in the room is very noticeable physically, she's very noticeable as unique in this milieu.

Henry: Is that a technique that you took from somewhere, or is that something that you devised yourself?

Charles Moore: Well, I think she devised it to some extent, and I picked up on that. She always had to wrestle with the point that it was considered a disadvantage to be a woman in the world in which she was moving. And she realized that though in certain respects it was objectively a disadvantage because of prejudice and so on, she could turn it to advantage. And I think one thing she understood very early on, because though she's a very sincere person she's also a very good actress, is that she could see the almost filmic quality of her pos