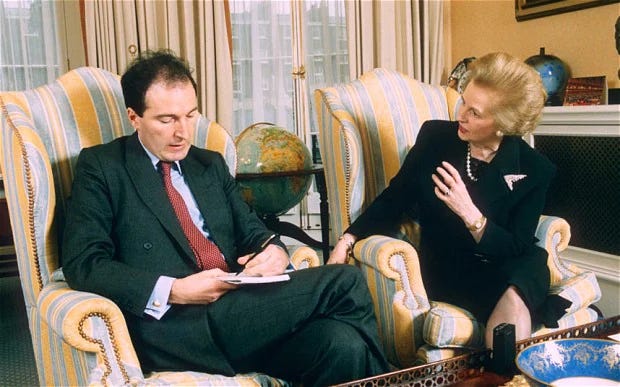

Robin Hanson, interview

Description

This conversation with economist and late bloomer Robin Hanson probably peaks towards the end, when we were bouncing ideas around, but the whole thing is highly interesting. Robin has a habit of rephrasing questions to make sure he is answering something specific, something I have seen in successful lawyers. Robin talked about his idea for a polymath department in universities, why desperation not inspiration was what made him change his life, how to talent spot late bloomers, and whether Robin might become lazy if he lived for ever (I don’t believe him). We also covered ems, the magic of motivation, signalling, and the importance of having a good spouse. Robin is a professor of economics, a former physicist and AI researcher, and the author of two books. He works at George Mason University and blogs at OvercomingBias. Although we didn’t cover it here, he is very interesting on the subject of aliens. This is a very selective description of what Robin does and you can and should read more about his work here. The page of wild ideas Robins thinks are true is especially good value. This is also a good summary of what drove Robin to change his life in his mid-thirties.

Henry Oliver: Did you always wanted to be an economist or are there versions of your life where you could have stayed in AI research?

Robin Hanson: I don't know. That is, my trajectory was one where I changed a number of times, and each time I wasn’t sure that I should change, I was making these guesses about what would be better, and then I guessed economics, but under alternative stars, I could have guessed different things or not made changes. A couple of years before I switched and decided to go into Econ, I applied to a bunch of graduate programs in Social Studies and Science, and I got accepted into some. And I even had told them I accepted their acceptance. And then a day later, I changed my mind. I decided not to do that. So I was on the borderline, I guess, of doing that.

Henry Oliver: And was that... Were you changing your mind for practical reasons or was there just deep uncertainty about what to do?

Robin Hanson: It was more, do I want to go into that world? Is that world going to be good enough or congenial for me? And I initially thought, yes, and then I guess let my subconscious tell me no.

Henry Oliver: So it was kind of instinct, you would just get a feeling and think, “Okay, don't go with it.”

Robin Hanson: Right, it was like... Part of it is about sort of the size of the world you could inhabit, so one of the nice things about physics where I started, and economics where I ended up is that you could just do a lot of things and call them that, and then there’s some other fields where you’re going to be pretty narrowly confined to things close to the prototype of that. And so science studies is more of that second sort, whereas economics is much broader, and physics was much broader as well. I think that I do well there. I think that’s done me very well to be in a much broader place where I can just do a lot of things and call it economics.

Henry Oliver: Do you think that one explanation of why there are late bloomers or how people become late bloomers could be that some people’s talents or interests are just naturally interdisciplinary or broad in the way you're describing, and that there are fewer maps for that kind of thing, and you just will get more late bloomers because it’s not straightforwardly specialized?

Robin Hanson: Well, so the question is, if you’re going to have a wider range, does that take longer training or longer time to recognize?

Henry Oliver: Right.

Robin Hanson: So, certainly, if most standard training is somewhat narrow, and if you’re going to have a broader range than that, then you’re deviating from the usual thing, and you might in fact need to do several things... So I guess somebody who’s just more uncertain about what narrow thing they want to do might similarly take longer, but somebody who’s just more inclined to have a wider range, that also just might take longer both to figure out that that’s what you want and to realise that the wider range just means you’re going to take longer training for the wider range.

Henry Oliver: So in one interview you said this, “Early in life you're a seller not a buyer.” Can you tell us what you mean by that?

Robin Hanson: Well, many people think about what career they want and what life they want, as if they are the main consumer of it, as if it’s about what they want out of it, and when you’re independently wealthy, say, then you could just decide what you wanted to do with your life based on what you liked because you can pay for it. If it’s a job or a career and you need a job or a career to survive, then you can’t just look at what you might want to get out of it, you’ll have to have other people get something out of it. And so that’s the sale that you’re selling yourself to other people. What can they get out of you? So you want to keep an eye on what you want to get out of it, but it isn’t enough, you know, if you decide, I love singing, so I’m going to be a singer. Well, that may not work if the world doesn’t love your singing, you’ll need to pay attention to what the world likes from you, for a while at least, and then if you get some idea of a range of things the world might be okay with from you, then you can start to think about which of those you prefer.

Henry Oliver: And this was the sort of thing you were realising when you worked at NASA?

Robin Hanson: So... I mean, honestly, for my early life, I really wasn't paying attention to buyers, I was just paying attention to what I wanted, and I would just change my mind about what I wanted, and then I would see if anybody else would let me do that, and if somebody else would, then I just switched. But I didn't try to become a singer or actor or something where it’s sort of known to be much more competitive, or Olympic athlete or something else, I wasn't trying to be those things, but I was maybe more on the edge of what I could get away with.

Henry Oliver: But you were doing something pretty competitive?

Robin Hanson: Well, initially, I was just being a grad student and applying to various grad student programs, and so I guess I was good enough to get into the grad student programs, and then I wanted to do computer research, and so I went, asked, applied for jobs and I got some jobs, and so it's more competitive than being a janitor, I guess but...

[laughter]

Robin Hanson: Not as competitive as trying to be an actor or a musician.

Henry Oliver: This is the sort of thing that people often advise you to do, so it’s like the Steve Jobs thing like, “Do calligraphy, do whatever you feel like, and it'll all sort of work out and you'll pull the threads together later,” but you seem to be saying, “Well, it’s one way of living a life, but it’s maybe not a good way.”

Robin Hanson: Well, you have to make a judgment of just how selective something is and how selective you are, right? It’s a matching thing, so I don't think... I mean, so I think it’s basically a brag to tell everybody that I always just did what I wanted. I mean, because some people can get away with that, and you’re basically saying, “I was good enough to get away with that, I could do that, I could pull it off, because I was in high enough demand, I was good enough.” And so I... It is a brag and it does apply to some people, but you have to realize, if you’re just taking it as some sort of inspiration and attitude toward life advice, it’s not going to work for everybody, and so... Now, you’ll have to ask just how good are you and how lucky do you feel punk, about how selective you can be. So, for most people, say, who might be listening to this, they don’t have to just take the first job that appears to them, right? They have some ability to select among jobs out there, and they should use that ability to think about which things they would like better, but they can’t just ask, “What does my heart love?” And just do that, regardless of what the world seems to offer or what abilities they seem to have, and so that it’s a compromise.

Henry Oliver: If you were talent spotting or recruiting, and someone came with a CV a bit like yours, and they said, “Well, I’ve just been doing the stuff I wanted to do,” would this count against them, would this count in their favour, like how would you assess that now?

Robin Hanson: So in some sense, the person I would be most able to assess would be someone who is very like me, that is, when I take a very unusual life path, I’m just going to be much worse at judging people who took other life paths, I’m not going to know who’s good or not in thos