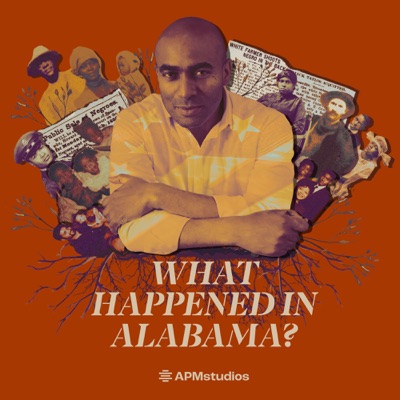

EP 10: Epilogue

Description

In the final episode of What Happened In Alabama, Lee considers the man his father became, despite the obstacles in his way. Later, Lee goes back to Alabama and reflects with his cousins on how far they’ve come as a family. Now that we know what happened, Lee pieces together what it all means and looks forward to the future.

Over the last nine episodes, you’ve listened to me outline the impact of Jim Crow apartheid on my family, my ancestors and me. I’ve shared what I’ve learned through conversations with experts, creating connections to how the effects of Jim Crow manifested in my own family.

In the process of this work I lost my father. But without him, this work couldn’t have been accomplished.

My name is Lee Hawkins and this is What Happened In Alabama: The Epilogue

Rev. James Thomas: You may be seated. We come with humble hearts. We come, dear Jesus, with sorrow in our hearts. But dear Jesus, we know that whatever you do,dear God,it is for your will and purpose. And it is always good.

We buried my father on March 9, 2019. His funeral was held at the church I grew up in. Mount Olivet Baptist Church in St. Paul Minnesota.

Rev. James Thomas: Dear God, I pray that you would be with this family. Like you have been with so many that have lost loved ones and even one day we all know we are going to sleep one day.Thank you for preparing a better place for us.

Mount Olivet’s pastor, Rev. James Thomas, knew my parents well, especially since my father was part of the music ministry there for 30 years. It was a snowy day, but people came from all over Minnesota and from as far away as Prague to pay their last respects. I looked at the packed parking lot and all the cars lined up and down the street, and I felt a sense of gratitude in knowing that my dad had played such a strong role in so many people’s lives, not just the lives of his own children and family.

Rev. James Thomas: Brother Leroy is probably playing the guitar over there. We can hear him with that squeak voice “yeeeee.”

Jalen Morrison: We could talk about Prince, we could talk about gospel music. He was even up on the hip hop music, too, which kind of shook me up. But I was like, okay, Grandpa [laughter]

Naima Ferrar Bolden: He really just had me seeing far beyond where I could see. He had me seeing far past my circumstances. He really changed my perspective, and that was just life altering for me ever since I was a little girl.

Herman Jones: He just had the heavy, heavy accent. He still had that booooy. But you know,he was always smiling, always happy all the time. You know, just full of life.

As I sat and listened to all the speeches that came before my eulogy of my dad, I couldn’t help but recognize both the beauty of their words and the extent to which my father had gone to shield so many of the people he loved from the hardest parts of his life—especially Alabama. It was as if he didn’t want to burden them, or, for most of our lives, his children, with that complexity. Most people remembered and honored him as that big, smiling, gregarious man with the smooth, first tenor voice, who lit up any space he was in and lit up when his wife, children, grandchildren, family, or friends walked into a room. He loved deeply; and people loved him deeply in return. And though he was victimized under Jim Crow, he was never a victim. In fact, after he sat for those four years of interviews with me for this show, opening up the opportunity for so many secrets to be revealed, he emerged as even more of a victor.

In our last conversation, he told me he wasn’t feeling well and that he had been to the doctor three times that week, but was never tested for anything. And Dad, after that third visit, he just accepted it. I do wonder if there was ever a time in those moments that he had a flashback to his mother being sent home in a similar way - 58 years prior - but from a segregated Jim Crow Alabama hospital. I don’t know. I’ll never know.

Tony Ware: Yeah. Mine. You know, I would always ask my mom, you know, about Alabama. You know, she was one of the five that came up here.

That’s my cousin Tony Ware. His mom was my Aunt Betty. The “five” that he’s talking about were my Dad’s siblings who migrated to Minnesota from Alabama - my aunts Helen, Toopie, Dorothy, Betty, and my Dad.

Tony Ware: They kind of hung around together and they would always have sit downs where they would talk. Get a moon pie, a soda. Hmm. Some sardines.

Lee Hawkins: Cigarettes.

Tony Ware: Cigarettes, sardines. And they would start talking. And some white bread. And they would sit there and talk and we would hear some of it. I sat in my mom's lap, and you know, they're talking about this, and it's like they just went into a different world.

When I was a kid in Minnesota, I loved when my dad’s sisters and their kids would come over. Us cousins would play hide-and-seek and listen to our music while our parents sat around the dining room table, talking and laughing, and listening to their own music. Our soundtrack was always great – Prince, Michael Jackson, New Edition, Cameo – but theirs was, too, with Curtis Mayfield, Aretha Franklin, Jerry Butler, Johnny Taylor, and Bobby Womack. The food was even better. They’d talk over one another, smoke clouding the air under the chandelier, and my allergy-sensitive nose could detect that smell from three rooms away. Sometimes, I’d sneak a quick sip from an unattended can of beer in the kitchen. Despite the bitter taste, getting away with it always gave me a thrill. But then, someone would mention the word “Alabama,” and that festive energy would suddenly vanish.

Tony Ware: But I heard Alabama. I heard this. I heard names that I never, you know, heard, you know, because all I knew was my aunt Dorothy, Lee Roy, you know, all I knew was. But then I heard certain names, uncles such and such. And I'm like, Who? Who, what, what?

To us as kids, "Alabama" was more than a place—it was a provocative word that brought a suffocating heaviness to our lives. My cousin Gina remembers, even as a child, that mysterious word and the weariness it triggered in her mother. It left her feeling utterly helpless.

Gina Hunter: And I would just sit there and listen to them talk about home and all the things that bothered them. Oh, my God. And yeah, it would hurt my feelings because I would see my mom just break out and cry for nothing. They would be talking and a song would be playing and Betty would just kind of get, she'd well up.

Lee Hawkins: Yeah.

Gina Hunter: And I'm like, Why are they so sad? Why are they so depressed? They they're together. They've got their kids. We're visiting, we're having fun. But it wasn't fun for them.

That veil of secrecy our parents kept around Alabama, prevented us from seeing it as anything other than ground zero for, in our family, dreadful despair. Even when they talked about the happy memories— the church revivals that they called “big meeting,” and picking fresh strawberries right off the vine – it seemed like a thread of fear just wove through almost every story.

Tony Ware:I knew something was going on more than what I knew here, you know, at a young age. So. I was always interested in finding out. But through my mom, you know, she she would talk about how nice it was down there, how beautiful it was down there. But she never wanted to go back there.

And as Gina remembers– and I agreed– it colored every facet of how they raised us. As she spoke, I just sat there, marveling at the fact that she could have replaced her mom’s name with my dad’s name, or any one of those siblings, and her observations would still be spot on.

Gina Hunter:My mom was and Aunt Helen, they were super, super close. And there was always just a deep seeded paranoia of people in general, just like everything. And I would think, why are these people why are they so scared and nervous and afraid of life and people and experiencing things? It seemed like it led them to live a super sheltered life.

The central question of this podcast is, "What happened in Alabama?"

What happened was Jim Crow apartheid—a crime against humanity committed by the American government against five generations of Black families like mine. This apartheid lasted for nearly hundred years, officially ending in 1964, and created generations of people who perished and millions who survived. I refer to these individuals as Jim Crow apartheid survivors. However, America has yet to acknowledge that Jim Crow was apartheid, that it was a crime against humanity, and that the millions of people who lived through it should be formally recognized as survivors.

In the prologue, I explained that so-called Jim Crow segregation was not merely about separate water fountains and back-of-the-bus seating. Through the accounts of family trauma I’ve shared, we now understand it was a caste system of domestic terrorism and apartheid, enforced by a government that imposed discrimination in every aspect of life through laws and practices designed to maintain white