Integration Generation

Description

Host Lee Hawkins investigates how a secret nighttime business deal unlocked the gates of a Minnesota suburb for dozens of Black families seeking better housing, schools, and safer neighborhoods. His own family included.

Transcript

Intro

LEE HAWKINS: This is the house that I grew up in and you know we're standing here on a sidewalk looking over the house but back when I lived here there was no sidewalk, and the house was white everything was white on white. And I mean white, you know, white in the greenest grass.

My parents moved my two sisters and me in 1975, when I was just four years old. Maplewood, a suburb of 25,000 people at the time, was more than 90% white.

As I rode my bike through the woods and trails. I had questions: How and why did these Black families manage to settle here, surrounded by restrictions designed to keep them out?

The answer, began with the couple who lived in the big house behind ours… James and Frances Hughes.

You’re listening to Unlocking The Gates, Episode 1.

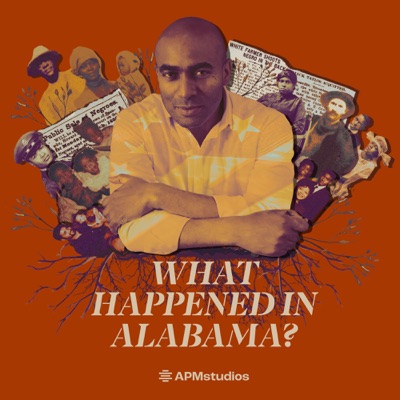

My name is Lee Hawkins. I’m a journalist and the author of the book I AM NOBODY’S SLAVE: How Uncovering My Family’s History Set Me Free.

I investigated 400 years of my Black family’s history — how enslavement and Jim Crow apartheid in my father’s home state of Alabama, the Great Migration to St. Paul, and our later move to the suburbs shaped us.

My producer Kelly and I returned to my childhood neighborhood. When we pulled up to my old house—a colonial-style rambler—we met a middle-aged Black woman. She was visiting her mother who lived in the brick home once owned by our neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Hutton.

LEE HAWKINS: How you doing? It hasn't changed that much. People keep it up pretty well, huh?

It feels good to be back because it’s been more than 30 years since my parents sold this house and moved. Living here wasn’t easy. We had to navigate both the opportunities this neighborhood offered and the ways it tried to make us feel we didn’t fully belong.

My family moved to Maplewood nearly 30 years after the first Black families arrived. And while we had the N-word and mild incidents for those first families, nearly every step forward was met with resistance. Yet they stayed and thrived. And because of them, so did we.

LEE HAWKINS: You know, all up and down this street, there were Black families. Most of them — Mr. Riser, Mr. Davis, Mr. White—all of us can trace our property back to Mr. Hughes at the transaction that Mr. Hughes did.

I was friends with all of their kids—or their grandkids. And, at the time, I didn’t realize that we, were leading and living, in real-time, one of the biggest paradigm shifts in the American economy and culture. We are the post-civil rights generation—what I call The Integration Generation.

Mark Haynes was like a big brother to me, a friend who was Five or six years older. When he was a teenager, he took some bass guitar lessons from my dad and even ended up later playing bass for Janet Jackson when she was produced by Minnesota’s own Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis.

Since his family moved to Maplewood several years before mine, I called him to see what he remembered.

MARK HAYNES: "It's a pretty tight-knit group of people,"

Mark explained how the community came together and socialized, often –

MARK HAYNES: "they—every week, I think—they would meet, actually. I was young—maybe five or six.

LEE HAWKINS: And what do you remember about it? I asked. What kind of feeling did it give you?

MARK HAYNES: It was like family, you know, all of them are like, uh, aunts and uncles to me, cousins. It just felt like they were having a lot of fun. I think there was an investment club too."

Herman Lewis was another neighbor, some years older than Mark—an older teenager when I was a kid. But I remember him and his brother, Richard. We all played basketball, and during the off-season, we’d play with my dad and his friends at John Glenn, where I’d eventually attend middle school. Herman talked to me about what it meant to him.

HERMAN LEWIS: We had friends of ours and our cousins would come all the way from Saint Paul just to play basketball on a Friday night. It was a way to keep kids off the street, and your dad was very instrumental trying to make sure kids stayed off the street. And on a Friday night, you get in there at five, six o'clock, and you play till 9, 10 o'clock, four hours of basketball. On any kid, all you're going to do is go home, eat whatever was left to eat. And if there's nothing left to eat, you pour yourself a bowl of cereal and you watch TV for about 15 to 25-30, minutes, and you're sleeping there, right in front of the TV, right?

LEE HAWKINS: But that was a community within the community,

HERMAN LEWIS: Definitely a community within the community. It's so surprising to go from one side of the city to the next, and then all of a sudden there's this abundance of black folks in a predominantly white area.

Joe Richburg, another family friend, said he experienced our community within a community as well.

LEE HAWKINS: You told me that when you were working for Pillsbury, you worked, you reported to Herman Cain, right? We're already working there, right? Herman Cain, who was once the Republican front runner for President of the United States. He was from who, who was from the south, but lived in Minnesota, right? Because he had been recruited here. I know he was at Pillsbury, and he was at godfathers pizza, mm hmm, before. And he actually sang for a time with the sounds of blackness, which a lot of people would realize, which is a famous group here, known all over the world. But what was interesting is you said that Herman Cain was your boss, yeah, when he came to Minnesota, he asked you a question, yeah. What was that question?

Joe Richburg: Well, he asked me again, from the south, he asked me, Joe, where can I live? And I didn't really understand the significance of that question, but clearly he had a sense of belonging in that black people had to be in certain geographic, geographies in the south, and I didn't have that. I didn't realize that was where he was coming from.

Before Maplewood, my family lived in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood—a thriving Black community filled with Black-owned businesses and cultural icons like photojournalist Gordon Parks, playwright August Wilson, and journalist Carl T. Rowan.

Like so many other Black communities across the country, Rondo was destroyed to make way for a highway. it was a forced removal.

Out of that devastation came Black flight. Unlike white flight, which was driven by fear of integration, Black flight was about seeking better opportunities: better funded schools and neighborhoods, and a chance at higher property values.

Everything I’ve learned about James and Frances Hughes comes from newspaper reports and interviews with members of their family.

Mr. Hughes, a chemist and printer at Brown and Bigelow, and Frances, a librarian at Gillette Hospital, decided it was time to leave St. Paul. They doubled down on their intentions when they heard a prominent real estate broker associate Blacks with “the ghetto.” According to Frances Hughes, he told the group;

FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “You’re living in the ghetto, and you will stay there.”

She adds:

FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “I’ve been mad ever since. It was such a bigoted thing to say. We weren’t about to stand for that—and in the end, we didn’t.”

The Hughes began searching for land but quickly realized just how difficult it could be. Most white residents in the Gladstone area, just outside St. Paul, had informal agreements not to sell to Black families. Still, James and Frances kept pushing.

They found a white farmer, willing to sell them 10 acres of land for $8,000.

And according to an interview with Frances, that purchase wasn’t just a milestone for the Hughes family—it set the stage for something remarkable. In 1957, James Hughes began advertising the plots in the Twin Cities Black newspapers and gradually started selling lots from the land to other Black families. The Hughes’s never refused to sell to whites—but according to an interview with Frances, economic justice was their goal.

FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “Housing for Blacks was extremely limited after the freeway went through and took so many homes. We wanted to sell to Blacks only because they had so few opportunities.”

By the 1960s, the neighborhood had grown into a thriving Black suburban community. The residents here were deeply involved in civic life. They attended city council meetings, started Maplewood’s first human rights commission, and formed a neighborhood club to support one another.

And over time, the area became known for its beautiful homes and meticulously kept lawns, earning both admiration and ridicule—with some calling it “The Golden Ghetto.”

Frances said:

FRANCES HUGHES (ACTOR): “It was lovely. It was a showplace. Even people who resented our being there in the beginning came over to show off this beautiful area in Maplewood.”

And as I pieced the story together, I realized it would be meaningful to connect with some of the elders who would remember those early days

ANN-MARIE ROGERS: In the 50s, Mr. Hughes decided he was going to let go of the farming. And it coincided with the with 94 going through the RONDO community and displacing, right, you know, those peopl