TEN Things I Learned from Jordan Peterson

Description

Dear readers, the following article is taken from the transcript of my latest YouTube video. I hope you enjoy!

I've learned many things from Jordan Peterson since he came on the public scene in 2016. I've learned things about psychology, morality, philosophy and even about Scripture and the Christian faith, things that have bolstered my understanding as a Christian philosopher and theologian.

So without further ado, ten things I learned from Jordan Peterson.

1. The Reality and Importance of Personality

Jordan Peterson is a personality psychologist. Following Carl Jung, he believes in the divisions between different personality traits that can be discovered through empirical study. He’s an advocate, in particular, of the recent Big Five model of personality. In the Big Five, there are five traits along which human beings can vary, openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, assertiveness and neuroticism.

Now, I used to be a bit of a skeptic about psychology in general, but personality in particular. Anytime someone tried to put me in a psychological box, I would resist it. I would hear about the Myers Briggs scale and be put into a category, whatever it was, INTJ, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. It never made any sense to me. It never felt accurate to me.

The interesting thing is, the Big Five is not about putting people in personality types. It's about traits that vary independently.

And so since I've learned about this, you start to see it everywhere. Some people are more extroverted, some less so and more introverted. Some people are more assertive than others. Some people more open to intellectual experience and ideas and so on.

And I think a lot of us resist this out of a sense that it puts us, of course, in a box or that it limits what we can change, what we can become. But there's also a deep reality to this. Not everything about human personality is malleable, and more importantly, some things in human personality are given.

What was even cooler to understand about personality was that so many other aspects of human differences can reduce down to personality differences, differences of ideology, whether that’s in theology or politics.

Try to tell me with a straight face that the difference between a Pentecostal and a Presbyterian isn't a difference of personality!

The same goes for liberals and conservatives. These are very much personality types. People who are extremely high in the trait of compassion, are strongly inclined to be liberal. It doesn't mean they're automatically more moral or righteous for doing so that compassion can lead them astray. It can lead them to be compassionate when it's time for judgment or boundaries.

But it really helps to understand that people don't get their ideas out of nowhere. We can also lower the temperature of ideological disagreements when we realize that we're all mostly just expressing our existing personalities.

2. The Psychology of Evil

Now this is one I'm still processing, but Jordan Peterson, following other psychologists, identifies the dark triad traits of narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy, as the psychological causes of evil behavior.

And I used to think that it was just liberals, in the fundamentalist Christian sense, that believed that there were psychological causes of evil. Isn't evil just caused by sin, just by doing the wrong thing. “BAH — I want to do evil!” Isn't that how evil is explained?

But when you think about it, people vary greatly in their capacities and tendencies to do evil. Not everyone is evil in the same degree, and that creates a kind of catch-22, which is that if some people are more violent by nature, aren't they to that extent, off the hook? Isn't there a sense in which, by explaining their behavioral tendencies, we no longer view them in an explicitly moral sense.

Now you might just say this is the problem of free will, and to some extent it is, but I think it's a problem we all have to wrestle with.

No one does evil without a cause.

No one does evil without some kind of explanation or backstory.

It's not all Freudian backstories about how we were brought up.

Many of them are naturally existing differences in personality traits and tendencies, including the dark triad.

3. The Interest of Allegorical, Moral and Psychological Readings of Scripture

Now, throughout my theological education in a Christian seminary, I was taught to be wary of moral and even allegorical interpretations of Scripture.

Scripture has a literal sense. It says this is what happened, and that's what it means.

If it has a moral application, we risk the idea of moralism, of trying to justify ourselves before God or save ourselves through our own moral action, rather than by accepting the grace of God. All the Old Testament stories, which we might interpret as morality tales, actually foreshadow Jesus Christ and everything that he did for us. So we shouldn't try to be like David fighting our giants, we should accept that Jesus was the David who fought Goliath for us.

But now I've seen that this is very narrow, and it gives up an extremely appealing and compelling dimension of the scriptures.

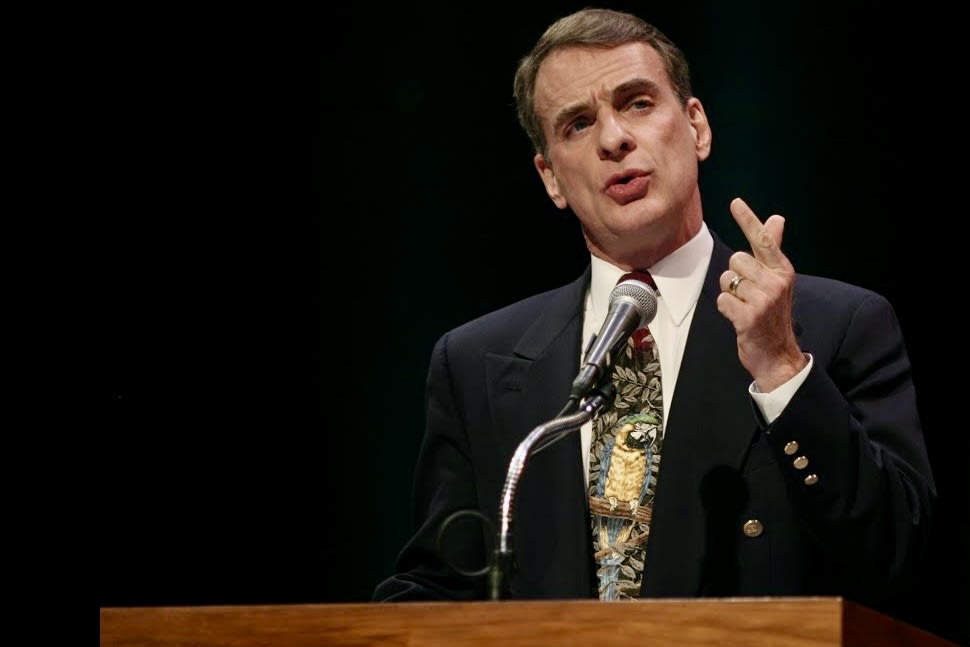

Jordan Peterson, contrary to all those Protestant Christian theologians, packed auditoriums by talking about the allegorical and moral and psychological dimensions of Scripture, the things that these could mean and the ways they could apply to our lives even caveat if they weren't true.

And now I see more and more the poverty of trying to do with just the story of what Jesus did for us. One recent author calls it “The Abridged Gospel.” (Check out Jordan Raynor’s The Sacredness of Secular Work.)

And Jordan Peterson, while we don't actually know if he believes that specific part of the gospel, believes in the further dimensions of the scriptures, both those that precede Christ's coming, the moral teaching, the Old Testament, law and those that come after it, the third use of the law, the application of the Christian scriptures, the Christian message to our life, the life of self, sacrifice and denial that Christ called us to.

That I think should transform Christians view of what our preaching and our message and our evangelism ought to look like.

If you enjoy content like this, please hit like and subscribe below. That'll help me to make more articles like this and videos like the one this is based on. If you like consuming this in video form, check out my YouTube page.

The Natural Theologian is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

4. The Existentialist Argument for the Limits of Materialism

Now I wouldn't be surprised if you had no idea what I was talking about here, but this is actually something from the very earliest lectures that I heard of Jordan Peterson, and from the opening pages of his book, Maps of Meaning.

Jordan Peterson, philosophically, is a Heideggerian, and Heidegger was an opponent of anyone who reduced human life and metaphysics down to the material, to pure science. And he did so not on the basis of a kind of Cartesian or spiritual dualism or an argument that mind was more than matter.

He did so on the basis of the idea that human beings fundamental orientation to the world, our fundamental way of knowing the world, is not scientific or theoretical. Our fundamental mode of being in the world is practical. It is to see things as ripe for action, to see the value in things, the valence, to see affordances for our action.

And Jordan Peterson put it this way:

It’s not only matter that exists; what matters also exists.

— Jordan Peterson (somewhere)

Other Heideggerian philosophers have echoed this, like John Haugeland and Hubert Dreyfus. John Haugeland’s festschrift is called Giving a Damn, because if you give a damn about things, then you're not a materialist. You believe that there is value and disvalue.

And so by that alone, Jordan Peterson disproved materialism.

5. Wisdom and Morality Don’t Have to Come from the Bible (especially wisdom)

Now, as a Christian by background, there's a tendency for Christians to think that all moral truth comes from the Bible. There's no other source for it. You can't get it from just human reflection or philosophy or reading books of ethics by secular philosophers. Now, instead, you've got to go straight to the Bible and find out what God directly commanded us.

But this is a very narrow view of morality. As CS Lewis said in the opening pages of Mere Christianity, everyone's making moral claims all the time. You took a bit of my orange. Now, give me a piece of yours. The smallest little moral attitudes we have that we give expression to show that we actually all believe in morality. We can't get rid of it.

Now Jordan Peterson doesn't get his morality, ultimately, from the Bible, or even what he does get from the Bible, he confirms, through psychology, science and biology. And this is important because it's very narrow to try to get all your morality from the Bible. We also have th