There IS Common Ground Between Believers and Unbelievers

Description

A woman was interviewing for a philosophy professorship at a Catholic university. Though she respected the intellectual tradition of the university, she was not herself Catholic. She hoped to find there similar respect for her own thinking, whatever its metaphysical conclusions.

The interview began well. Potential future colleagues discussed her research and gave her an opportunity to display her considerable knowledge of epistemology and continental thought.

Then a new voice chimed in. A crotchety but not-yet-old Catholic man began to dig into her moral and political views. He settled on the topic of abortion. How could she condone the murder of innocent unborn children? What other wickedness would she countenance?

She tried to respond that, while she was not a Catholic herself, she admired the moral tradition of Catholic theologians and philosophers. Nevertheless, respectfully, she disagreed with it. That was not good enough for the crotchety Catholic philosopher.

While the interview was otherwise successful, its final phase sapped the woman of energy. It left her desiring to be employed as far from this university as possible.

In her place, the university hired a different pro-choice secular philosopher: My dissertation advisor, who fortunately was not subjected to the same treatment.

As a Christian philosopher, I struggle to comprehend why a secular analytic philosopher’s failure to be pro-life would be surprising. And anyway, why would we focus on our points of disagreement, rather than our points of agreement - the rigor of philosophical thought, the merits of the candidate’s research, and the mission of the philosophy department?

Yet often, we approach people who hold different views than us in exactly the way this professor approached the interviewee. In those moments, we are tempted to think that our ideological differences are so fundamental that there is no common ground between us.

But there is common ground, and we’re standing on some of it.

There Is No Common Ground

“There is no common ground between believer and unbeliever.”

That was a dictum of the seminary I attended. Its presuppositionalist philosophy held that Christians and non-Christians do not differ merely in our conclusions. We differ at every level of thinking down to the most fundamental presuppositions of thought - even on the principles of logic and mathematics themselves.

“No common ground” was intended as a pious affirmation of our commitment to have a distinctively Christian worldview. Yet in our zeal to be as Christian as possible, we ignored the deeply divisive and partisan effects of the statement.

Imagine if a progressive activist said, “There is no common ground between progressives and conservatives!” Would that person strike you as open-minded and willing to hear opposing perspectives? Would you be likely to feel comfortable having a conversation with them about matters moral or political?

Personally, I would fear being written off for my beliefs, or being thought evil or irredeemable.

But that’s what we Christians do if and when we say: “There is no common ground between believers and unbelievers.” And even if we don’t say those words, we often act like it.

I wrote about this a few months ago in “Berating the Godfearers.” My friend “Brent,” who is interested in Christianity, was dismissed and shouted at for not being a six-day creationist by a number of evangelical Christians on a Zoom meeting. What had happened? The evangelical guys found one point of disagreement and went hard at it. But that’s not the path to a productive conversation.

As I put it then, the evangelical guys pursued conversion rather than conversation. And ultimately, it was a poor means of persuasion, forget conversion.

Common Ground at F3: Fitness, Fellowship, and Faith

A couple weeks ago, I hosted a philosophy night with my friends from F3, “Fitness, Fellowship, and Faith.” I was especially excited to talk about common ground with them because F3 itself has been for me a major object lesson.

At the end of every workout, someone says, “F3 is not a religious organization. All we ask is that you believe in something higher than yourself. It could be Jesus, Buddha, Allah, or the man next to you.”

But then, if the person is a Christian, he continues, “But I am a Christ-follower, so I’m going to close us out in a Christian prayer. Join me or respect the time. Dear God…”

There’s something very remarkable about this. Americans think that any public display or mention of religion is an attempt to impose faith on others. And many religious Americans publicly express their faith in a very impositional way.

But at F3, I learned a different way of interacting with non-Christians. Our faith or religious commitments are known, but they are not imposed on others, and they are not the source of our commonality. Our commonality is that we just sweated and lifted a concrete block (“the coupon”) together for forty-five minutes. Our commonality is that we want to escape “sad-clown syndrome,” a problem which afflicts many American men. Our commonality is that we believe that there is something higher than ourselves – that living for self-gratification is the wrong goal.

This commonality clears enough ground actually to discuss both normal life and deeper things. We have weekly “QSource” discussions in which we touch on themes of faith, virtue, manliness, community, and more. These discussions go deeper and engage more men than any church men’s group you’ve seen. I even instituted approximately monthly “philosophy nights” when we discussed a book over beer.

The key is that F3 discussions place Christians and non-Christians on a level playing field; we enter conversation as equal partners in the search for truth and goodness. I have indeed seen people become Christian through this. I’ve seen other people at least soften their stance on religion. And at a bare minimum, we are able to be open and understanding of one another’s perspectives.

This is the religion-friendly pluralist ethic on which America was founded. These days, most have more of a more secularist understanding - that religion shouldn’t be brought into the public square. Much better to do it in the manner of that polis within the polis, “F3 Nation.”

Finding Common Ground in Philosophy

My studies in philosophy are another of my attempts to disprove, “There is no common ground between believers and unbelievers.” In the first place, I’m studying philosophy, so none of my arguments can start from Christian premises. We proceed by reason alone, as it were.

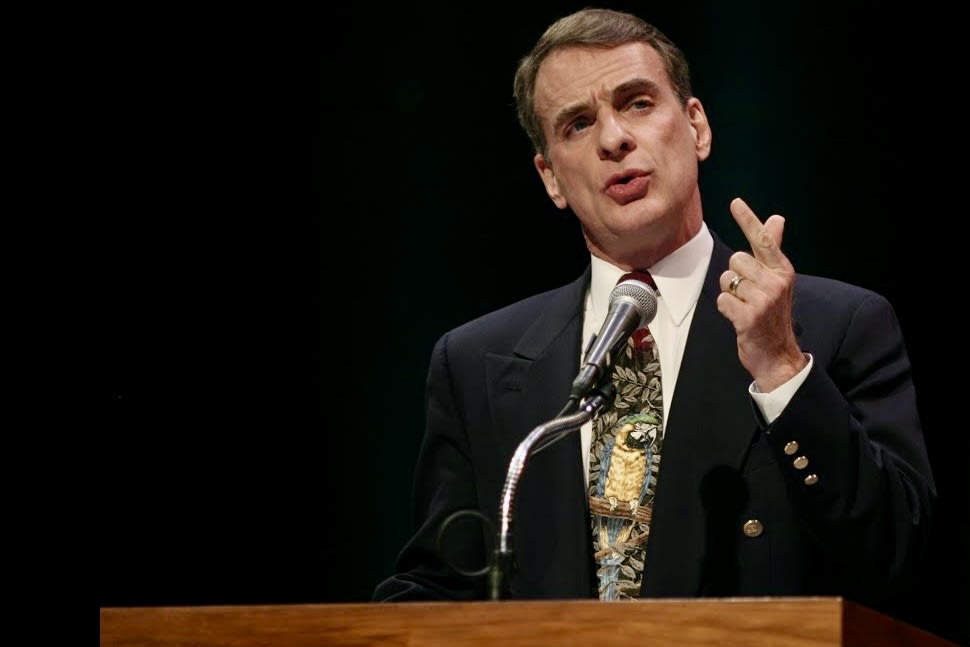

But in the second place, I sought out a non-Christian dissertation advisor as a test of the thesis that there can be common ground between believers and unbelievers.

Now, I first took a course on Plato’s ethics with Dr. B____. I detected that he took a very secular view of Socrates; Socrates was a purely secular guy, whom Plato had corrupted and spiritualized. Whatever seemed to point in a Christian direction could therefore be attributed to Plato, or to later Neo-Platonist interpretations, rather than to Socrates. Socrates was a utilitarian; he didn’t believe in an afterlife; and Platonism was and is consistent with a scientific worldview.

Almost the whole semester, my mind kept thinking of paper topics where I disagreed with Dr. B____. But finally, I realized that I would learn the most by writing about the one topic I’d discovered on which he and I agreed.

After that was a success, I asked him about advising my dissertation, and we followed the topic to the next point of agreement. Eventually, I realized that Dr. B____ and I agree primarily on one thing: Reality exists. We just disagree about what reality is like (i.e., everything else).

But I relish that point of agreement for this reason: I believe that the common ground between all of us, no matter what our different views, beliefs, convictions, faiths, is reality itself. Even the postmodernists who think that reality is nothing but a mental construct - we drive on the same streets, breathe the same air, encounter the same objects in our visual field and so on. No worldview, philosophy, belief, metaphysics, or any of it can obscure the fact that reality itself is the common ground between us.

The common ground between different worldviews is reality itself.

A Philosopher and an MS-13 Member Walk Into a Bar…

The process I went through with my professor can work with anyone. You may disagree with them about ten things, all