The state of Digital Transformation in 2020 and some follow-up on the disruption of Intel

Description

My apologies for the long lapse between writing essays. If I’m honest, the world has been just too much to afford me the mental space to think, write, edit and record these essays. I’ve taken on more responsibilities and simultaneously fell down the rabbit hole with the US presidential elections. And, despite not being directly affected by the ousting of the “Great Orange Liar”, I can’t help but be touched on a personal level. Seeing the once-great nation disintegrating in front of my eyes bothers me much. That’s all I’ll say for the moment.

On a more positive note, as we draw ever-closer to deploying what might be a solution to our number one problem of the novel coronavirus, I thought I’d take a look at what the pandemic has exposed and what digital transformation means today.

One last note on housekeeping, the keen-eyed will notice that I have moved this newsletter to my companies’ domain (dgtlfutures.com). Everything else stays the same and all the existing links still work. It is now easier to find, as it is at newsletter.dgtlfutures.com

The state of Digital Transformation in 2020

When the pandemic appeared to be a real threat to the countries in which it took hold, many including myself estimated that this might be the impetus required to get companies to start, deploy and finish their digital transformations. The reality couldn’t be further from the truth, and it comes back to some difficulties I’ve been discussing for years.

Let’s take a look at where we are in digital transformation today. I’ll go on to show what is missing, what is needed and how we get there.

The first wave - The implementation of computerised back-end systems

The likes of IBM with their AS/400 and DEC with their VAX minis and mainframes were the masters of this. Not because it was hard, but because it was easy and it was a licence to print money. Ever since the first VisiCalc spreadsheet showed the CEO that he or she didn’t need to manually calculate the columns and rows themselves (or have one of the minions to do it), it was inevitable that computerised system would penetrate deeper and deeper in businesses. Those that afforded the outrageous costs of the time, were given an advantage that had not been seen since the invention of the wheel (the innovation that disrupted the movement of atoms from one place to another).

Quickly, IBM and their competitors spun up massive sales teams that crisscrossed the globe demonstrating and selling stock control systems, basic accounting ledgers and simple statistical reporting programs. On the back of this, software-focused companies ramped up work producing ever more complex designs that piggy-backed on the already-deployed hardware. Being that the business model of the IBMs and DECs of the era was to sell high-margin hardware and lucrative support contracts for that hardware, they were pleased to let the software houses integrate their software as it made the hardware even more desirable.

This symbiotic relationship even gave rise to the “Killer App” moniker we use today.

The businesses that needed to make ever-quicker decisions wrote practically open cheques to the manufacturers, as they were confident that the returns on the investments would outdo the spend. And they were right to believe this, as the entire industry structured itself to become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

A long time ago, I interviewed for a support role in one of the world’s largest banks, in their London office. I was applying for a position as a support engineer that would be dispatched to the trading floor. I was genuinely intrigued by the floor and asked if it would be possible to see the environment in which I would be working. After a short pause, the IT manager agreed to the unusual request and led me down the stairs to the big oak doors that displayed an ominous sign on a big brass plate. “Do Not Feed The Animals” it read. I chuckled and braced myself for the spectacle that was a Trading Floor in the early 90s. I’ll tell that story another day. But what I most remember was that each trader had two complete AS/400 systems under their desks. This, a room with perhaps 60 to 100 people in it.

That would be a multi-million pound budget by today's rates. But this was standard issue, as the opportunity cost was so high for traders that were just that slightly slower than their competition during trading hours. Their killer app was the trading platform that operated on super-slim timing to augment the trader’s abilities.

The second wave - The paperless office

After the fury of this first wave of digital transformation, it was clear to businesses that they needed to go further, and hunting season was declared on paper—a hunting season that has not, by any stretch of the imagination, finished yet even in 2020.

But that is beside the point.

End-user facing documents and reports were the next low-hanging fruit, and businesses proceeded to digitise these objects as and when they could based on the technologies at their disposal. Very few companies bought software with the sole intention of moving paper reports to digital versions of themselves. It was just the icing on the cake for most. So now, timesheets, TP reports (see Office Space) and countless other document types were converted.

Operators would export data from the ERP systems like SAP, import them into Excel and produce the charts that ended up in Word and PowerPoint documents. But even at this stage, paper wasn’t entirely eliminated, as often these reports (and I see this still today) were printed out in colour and distributed manually or by mail (the physical internal and external postal systems) for analysis and treatment. At some point, people realised that this could be made more efficient. With the advent of internal email systems gaining popularity, sending the PPT over email was the method of choice that enabled faster and better “collaboration”.

I used the quotes, as, by today’s standards, this could be nothing but further from the truth of what collaboration is. The back-and-forth of individually saved and edited documents on the network led to an exponential growth in data storage needs for both the email systems and the personal data storage systems.

When working on sophisticated archiving systems, I discovered that it was not that uncommon to have approximately 100 copies of the same documents on the network. That email sent to 20 colleagues, saved on their “personal space” produces in one step 41 copies!

The third wave - The age of collaboration

When the apparent limitations of this model became apparent, and the software had caught up, we started to build-out specific collaboration software to address these limitations.

As a side note, it must be said that IBM was (not for the first time) way ahead of this curve. Whilst the likes of Novell and Microsoft were supplying the pipes to connect businesses with unstable and simplistic networking hardware, IBM bought and extended a company that built a virtually limitless collaboration system that was too much too early. Lotus Domino was the first “proper” collaboration tool that let business easily deploy just-what-was-needed software to decision-makers. It included storage, sharing, app-building and elementary database capabilities that were far ahead of the curve at the time. Its complexity and frankly, the hostile user interface was part of its downfall, but it was an essential step in the computing-business interface building world.

Fast-forward to pre-pandemic, and the state of collaboration today. We see that companies that had implemented the new generation of basic collaboration systems could provide some semblance of business continuity. Whilst those who hadn’t yet taken the steps, scrambled to implement tools, shoehorning them into day-to-day operations. With varying degrees of success, it should be noted. The pandemic has forced many companies to evaluate if the tools work. They work that is for sure, and work surprisingly well, as they are developed from years of research and experience testing. Forcing them on to unprepared staff will only expose the frailty of your operations if you don’t do the hard work of real digital transformation.

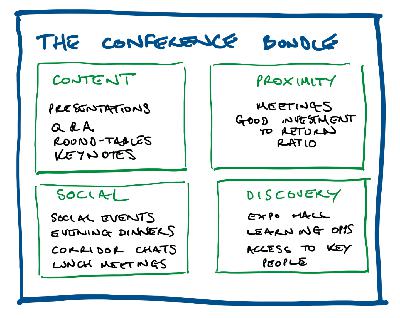

But back to the pandemic. Businesses that have been forced to close their doors to receiving public in their offices and shops have turned to their most pressing problem of managing the customer relationship. How do I sell to someone who would previously wander around my shop for 15 minutes before picking an item and purchasing it?

Facebook and WhatsApp, for example, have provided a means to interact with the client, and possibly vehicle some sales. I’d argue that those sales were probably not lost in the first place, but let’s not split hairs. However, they don’t address the fundamental problems of a wholesale shift in the customer journey fro discovery to purchase and beyond. Plasters on broken leg might make you feel a little better, but they don’t repair the break! So, as we progress in the pandemic, most are preoccupied with the customer-facing elements, ignoring the opportunity to implement real change that would set them up for the afterworld.

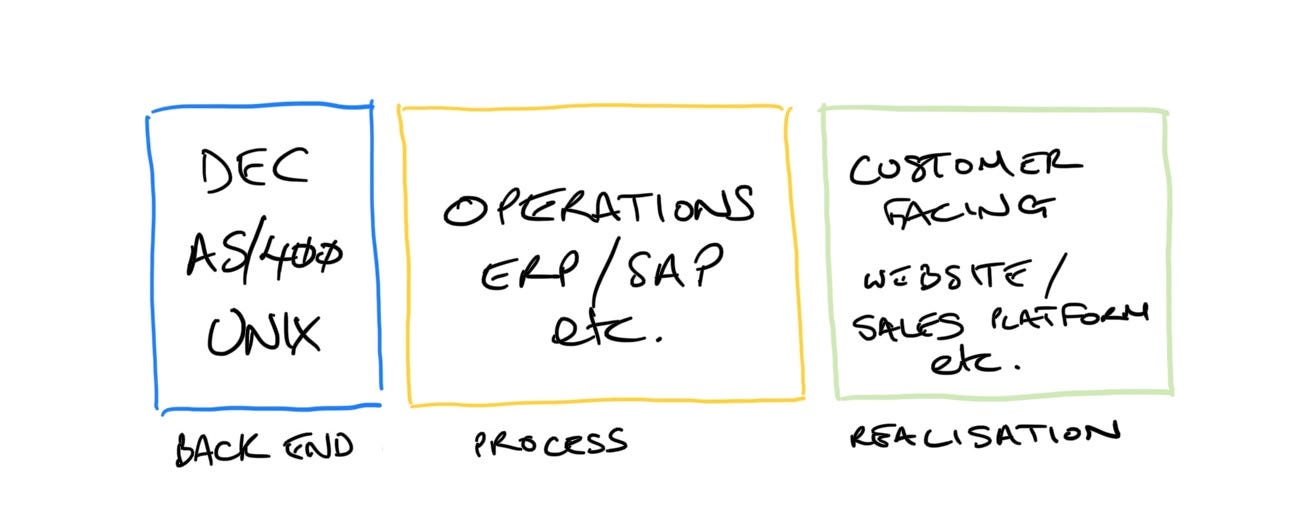

In trying to schematise the idea, I’ve settled on three blocks; the back-end, the operations and the customer-facing parts.

Source: Matthew Cowen

The back-end has been deployed for many years and is efficient at what it does. What is doesn’t do is the problem we have today, however. Legacy AS/400 and DEC systems are still prevalent all around the world. Those legacy systems are notoriously difficult to interface with, notoriously poor at real-time and notoriously poor at providing reusable data for business intellig