Vaccines, Tylenol, and Circumcision?!

Description

We’ve been working on this article for weeks. Poring over studies on the Tylenol-autism topic. Just before we got it scheduled to post... another soundbite.

At today’s Cabinet meeting, Health Secretary RFK Jr. claimed that “children who are circumcised early have double the rate of autism,” adding “it’s highly likely because they’re given Tylenol.” President Trump backed him up, saying there’s “a tremendous amount of proof or evidence, I would say as a non-doctor.”

Here’s just the tip of what’s wrong with this claim: Kennedy mentioned “two studies,” but didn’t specify which. A quick search turns up two likely candidates. One is a 2015 Danish registry study that found a modest statistical bump in autism diagnoses among circumcised boys, especially under age five. The authors themselves highlighted big limitations—such as incomplete circumcision data and the inability to prove causation. (By the way, the study never mentioned Tylenol, acetaminophen, or any pain medications. The researchers were investigating whether the circumcision procedure itself - the pain and stress - might be linked to autism.) The other is a 2013 ecological paper that used circumcision rates as a stand-in for acetaminophen exposure. Even its authors described it as “hypothesis-generating,” not proof. And just to underline how shaky the circumcision link was, a 2015 published critique of the Danish study pointed out that its autism findings rested on very small numbers and questionable assumptions.

But RFK Jr.’s real logical leap is collapsing these into one neat story: some circumcised boys get Tylenol for pain, and some are later diagnosed with autism—therefore, Tylenol causes autism. That’s like saying umbrellas cause car accidents because both are more common on rainy days. The studies don’t actually connect those dots. The Danish analysis wasn’t about Tylenol at all, and the ecological paper was little more than circumcision-as-proxy guesswork.

Kennedy’s stance? “None of this is positive, but all of it is stuff we should be paying attention to.” This immediately brought to mind that scene in Dumb and Dumber—when Lloyd Christmas hears his chances with Mary are “one out of a million” and responds: “So you’re telling me there’s a chance!”

Now, on to what we actually came here to discuss: the broader claims about Tylenol and autism that have pregnant women wondering if they really need to “tough it out”...

At a press conference on September 22, the Trump administration urged pregnant women to “tough it out” and avoid Tylenol, citing a link to autism. The claim surprised many, including the researchers whose work is being cited. Scientists say that’s not what the research shows. The strongest evidence to date shows that if there is any link, it’s not a cause-and-effect relationship.

Here’s what you should know…

For starters, acetaminophen is the active ingredient in Tylenol and many other over-the-counter medications, making this warning broader than just one brand.

The Review That Doesn’t Say What They Claim

The centerpiece of the government’s claim is a review of 46 studies published in August. Yes, 27 studies reported some association between acetaminophen and neurodevelopmental issues. In science and public health, “association” means that two things are related or connected in some way, but it does not mean that one causes the other. A third thing might be influencing the relationship and causing both of the first two things to happen at the same time. The review’s own lead author, Dr. Didier Prada, confirmed: “We cannot answer the question about causation—that is very important to clarify.”

He even used a perfect analogy: ice cream sales and violent crime both rise in summer, but nobody thinks Rocky Road causes assault. (Association, not causation.)

They also relied on the Navigation Guide, a framework built for environmental toxins, not medications. With medications, we can measure exactly what people took and when. But with environmental toxins—think lead paint from childhood homes or industrial chemicals from old factories—researchers have to guess based on decades-old records. The Navigation Guide was designed for those messy situations. Applied to medications—where we have prescriptions and clear records—it treats weak hints like strong evidence. Medical standards like GRADE correctly start with more skepticism about observational studies; the Navigation Guide doesn’t. Small, questionable associations get inflated into findings that seem more certain than they are.

The review gave high ratings to studies with fundamental flaws—including one where every single baby had detectable acetaminophen in their cord blood, making a true unexposed comparison impossible—while penalizing a massive Swedish sibling study for not having trimester-specific timing data. Reviews like this are extremely sensitive to how studies are weighted—small changes in weighting can flip the overall conclusion from positive to negative. When the methodology lacks transparency about these crucial decisions, readers can’t evaluate whether the conclusion reflects the data or the authors’ choices.

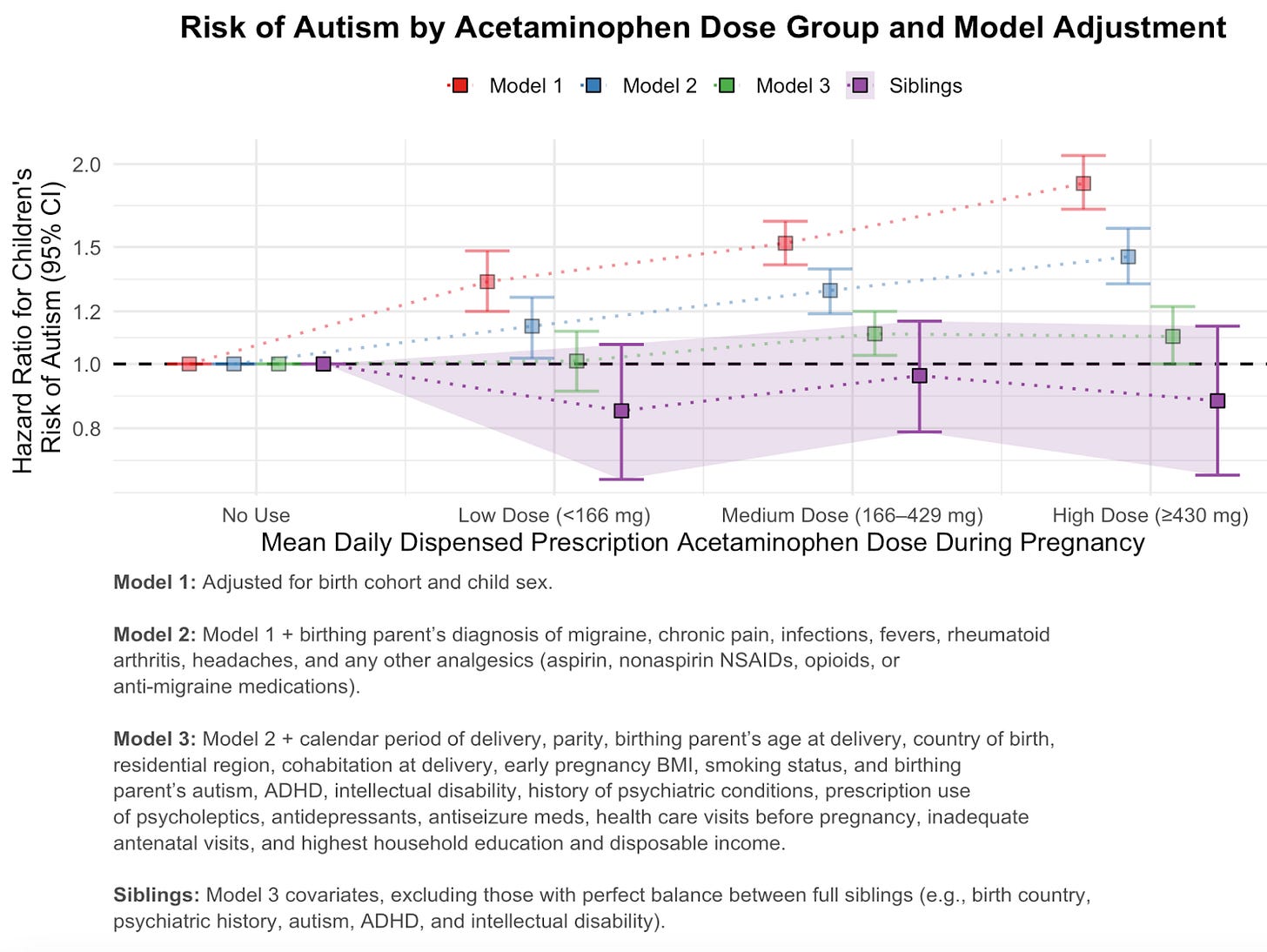

Finally, the review leaned heavily on ‘dose-response’ as a sign of causation. If a drug is harmful, higher doses should mean higher risk. But most dose-response patterns came from small or poorly adjusted studies. In the large Swedish sibling study—our best evidence—the gradient vanished once family factors were controlled (as indicated by the purple line below). Low, medium, or high use all showed essentially the same risk which hovered around no effect (as indicated by the black dashed line at HR=1), suggesting the apparent dose-response patterns indicated in red, blue, and green came from confounding by genetics, maternal health, or the underlying condition being treated rather than the medicine itself.

Credibility matters, too. The senior author, Harvard Dean Andrea Baccarelli, disclosed he was a paid expert witness for plaintiffs suing acetaminophen manufacturers. When a federal judge reviewed his testimony last December, she ruled it “lacked scientific evidence“ and dismissed every case.

What The Swedish Study Shows

The administration is overlooking the most rigorous evidence available: Sweden’s sibling study, which followed essentially every child born over two decades—2.5 million in total, including 186,000 exposed to acetaminophen during pregnancy.

Looking at the population as a whole, researchers initially saw a slight association