Discover The Convivial Society

The Convivial Society

The Convivial Society

Author: L. M. Sacasas

Subscribed: 66Played: 1,609Subscribe

Share

© L. M. Sacasas

Description

Audio version of The Convivial Society, a newsletter exploring the intersections of technology, society, and the moral life.

theconvivialsociety.substack.com

theconvivialsociety.substack.com

50 Episodes

Reverse

Hello all, The audio version keep coming. Here you have the audio for Secularization Comes for the Religion of Technology. Below you’ll find a couple of paintings that I cite in the essay. Thanks for listening. Hope you enjoy it.Cheers,Michael Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

I continue to catch up on supplying audio versions of past essays. Here you have the audio for “Vision Con,” an essay about Apple’s mixed reality headset originally published in early February. The aim is to get caught up and then post the audio version either the same day as or very shortly after I publish new written essays. Thanks for listening! Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

Just before my unexpected hiatus during the latter part of last year, I had gotten back to the practice of recording audio version of my essays. Now that we’re up and running again, I wanted to get back to these recordings as well, beginning with this recording of the first essay of this year. Others will follow shortly, and as time allows I will record some of the essay from the previous year as well. You can sign up for the audio feed at Apple Podcasts or Spotify. Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

At long last, the audio version of the Convivial Society returns. It’s been a long time, which I do regret. Going back to 2020, it had been my practice to include an audio version of the essay with the newsletter. The production value left a lot to be desired, unless simplicity is your measure, but I know many of you appreciated the ability to listen to the essays. The practice became a somewhat inconsistent in mid-2022, and then fell off altogether this year. More than a few of you have inquired about the matter over the past few months. Some of you graciously assumed there must have been some kind of technical problem. The truth, however, was simply that this was a ball I could drop without many more things falling apart, so I did. But I was sorry to do so and have always intended to bring the feature back.So, finally, here it is, and I aim to keep it up. I’m sending this one out via email to all of you on the mailing list in order to get us all on the same page, but moving forward I will simply post the the audio to the site, which will also publish the episode to Apple Podcasts and Spotify. So if you’d like to keep up with the audio essays, you can subscribe to the feed at either service to be notified when new audio posts. Otherwise just keep an eye on the newsletter’s website for the audio versions that will accompany the text essays. The main newsletter will, of course, still come straight to your inbox. One last thing. I intend, over the coming weeks, to post audio versions of the past dozen or so essays for which no audio version was ever recorded. If that’s of interest to you, stay tuned. Thanks for reading and now, once again, for listening.Cheers, Michael The newsletter is public and free to all, but sustained by readers who value the writing and have the means to support it. Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome back to the Convivial Society. In this installment, you’ll find the audio version of the latest essay, “What You Get Is the World.” I try to record an audio version of most installments, but I send them out separately from the text version for reasons I won’t bore you with here. Incidentally, you can also subscribe to the newsletter’s podcast feed on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Just look up The Convivial Society. Aside from the audio essay, you’ll find an assortment of year-end miscellany below. I trust you are all well as we enter a new year. All the best to you and yours! A Few Notable PostsHere are six installments from this past year that seemed to garner a bit of interest. Especially if you’ve just signed up in recent weeks, you might appreciate some of these earlier posts. Incidentally, if you have appreciated the writing and would like to become a paid supporter at a discounted rate, here’s the last call for this offer. To be clear, the model here is that all the writing is public but I welcome the patronage of those who are able and willing. Cheers!Podcast AppearancesI’ve not done the best job of keeping you all in loop on these, but I did show up in a few podcasts this year. Here are some of those: With Sean Illing on attentionWith Charlie Warzel on how being online traps us in the pastWith Georgie Powell on reframing our experience Year’s EndIt is something of a tradition at the end of the year for me to share Richard Wilbur’s poem, “Year’s End.” So, once again I’ll leave you with it.Now winter downs the dying of the year, And night is all a settlement of snow;From the soft street the rooms of houses show A gathered light, a shapen atmosphere, Like frozen-over lakes whose ice is thin And still allows some stirring down within.I’ve known the wind by water banks to shakeThe late leaves down, which frozen where they fell And held in ice as dancers in a spell Fluttered all winter long into a lake; Graved on the dark in gestures of descent, They seemed their own most perfect monument.There was perfection in the death of ferns Which laid their fragile cheeks against the stone A million years. Great mammoths overthrown Composedly have made their long sojourns, Like palaces of patience, in the grayAnd changeless lands of ice. And at PompeiiThe little dog lay curled and did not rise But slept the deeper as the ashes roseAnd found the people incomplete, and froze The random hands, the loose unready eyes Of men expecting yet another sunTo do the shapely thing they had not done.These sudden ends of time must give us pause. We fray into the future, rarely wroughtSave in the tapestries of afterthought.More time, more time. Barrages of applause Come muffled from a buried radio.The New-year bells are wrangling with the snow.Thank you all for reading along in 2022. We survived, and I’m looking forward to another year of the Convivial Society in 2023. Cheers, Michael Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

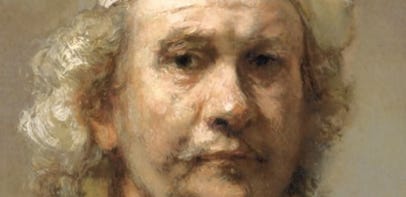

Welcome again to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. This post features the audio version of the essay that went out in the last installment: “Lonely Surfaces: On AI-generated Images.” For the sake of recent subscribers, I’ll mention that I ordinarily post audio of the main essays (although a bit less regularly than I’d like over the past few months). For a variety of reasons that I won’t bore you with here, I’ve settled on doing this by sending a supplement with the audio separately from the text version of the essay. That’s what you have here. The newsletter is public but reader supported. So no customers, only patrons. This month if you’d like to support my work at a reduced rate from the usual $45/year, you can click here: You can go back to the original essay for links to articles, essays, etc. You can find the images and paintings I cite in the post below. Jason Allen’s “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial”Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp”Detail from Pieter Bruegel’s “Harvesters” The whole of Bruegel’s “Harvesters” Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome back to the Convivial Society. In this installment, you’ll find the audio version of two recent posts: “The Pathologies of the Attention Economy” and “Impoverished Emotional Lives.” I’ve not combined audio from two separate installments before, but the second is a short “Is this anything?” post, so I thought it would be fine to include it here. (By the way, I realized after the fact that I thoughtlessly mispronounced Herbert Simon’s name as Simone. I’m not, however, sufficiently embarrassed to go back and re-record or edit the audio. So there you have it.)If you’ve been reading over the past few months, you know that I’ve gone back and forth on how best to deliver the audio version of the essays. I’ve settled for now on this method, which is to send out a supplement to the text version of the essay. Because not all of you listen to the audio version, I’ll include some additional materials (links, resources, etc.) so that this email is not without potential value to those who do not listen to the audio. Farewell Real LifeI noted in a footnote recently that Real Life Magazine had lost its funding and would be shutting down. This is a shame. Real Life consistently published smart and thoughtful essays exploring various dimensions of internet culture. I had the pleasure of writing three pieces for the magazine between 2018 and 2019: ”The Easy Way Out,” “Always On,” and “Personal Panopticons.” I was also pleasantly surprised to encounter essays in the past year or two drawing on the work of Ivan Illich: “Labors of Love” and “Appropriate Measures,” each co-authored by Jackie Brown and Philippe Mesly, as well as “Doctor’s Orders” by Aimee Walleston. And at any given time I’ve usually had a handful of Real Life essays open in tabs waiting to be read or shared. Here are some more recent pieces that are worth your time: “Our Friend the Atom The aesthetics of the Atomic Age helped whitewash the threat of nuclear disaster,” “Hard to See How trauma became synonymous with authenticity,” and “Life’s a Glitch The non-apocalypse of Y2K obscures the lessons it has for the present.” LinksThe latest installment in Jon Askonas’s ongoing series in The New Atlantis is out from behind the paywall today. In “How Stewart Made Tucker,” Askonas weaves a compelling account of how Jon Stewart prepared the way for Tucker Carlson and others: In his quest to turn real news from the exception into the norm, he pioneered a business model that made it nearly impossible. It’s a model of content production and audience catering perfectly suited to monetize alternate realities delivered to fragmented audiences. It tells us what we want to hear and leaves us with the sense that “they” have departed for fantasy worlds while “we” have our heads on straight. Americans finally have what they didn’t before. The phony theatrics have been destroyed — and replaced not by an earnest new above-the-fray centrism but a more authentic fanaticism.You can find earlier installments in the series here: Reality — A post-mortem. Reading through the essay, I was struck again and again by how foreign and distant the world of late 90s and early aughts. In any case, the Jon’s work in this series is worth your time. Kashmir Hill spent a lot of time in Meta’s Horizons to tell us about life in the metaverse: My goal was to visit at every hour of the day and night, all 24 of them at least once, to learn the ebbs and flows of Horizon and to meet the metaverse’s earliest adopters. I gave up television, books and a lot of sleep over the past few months to spend dozens of hours as an animated, floating, legless version of myself.I wanted to understand who was currently there and why, and whether the rest of us would ever want to join them. Ian Bogost on smart thermostats and the claims made on their behalf: After looking into the matter, I’m less confused but more distressed: Smart heating and cooling is even more knotted up than I thought. Ultimately, your smart thermostat isn’t made to help you. It’s there to help others—for reasons that might or might not benefit you directly, or ever.Sun-ha Hong’s paper on predictions without futures. From the abstract: … the growing emphasis on prediction as AI's skeleton key to all social problems constitutes what religious studies calls cosmograms: universalizing models that govern how facts and values relate to each other, providing a common and normative point of reference. In a predictive paradigm, social problems are made conceivable only as objects of calculative control—control that can never be fulfilled but that persists as an eternally deferred and recycled horizon. I show how this technofuture is maintained not so much by producing literally accurate predictions of future events but through ritualized demonstrations of predictive time.MiscellanyAs I wrote about the possibility that the structure of online experience might impoverish our emotional lives, I recalled the opening paragraph of the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga’s The Waning of the Middle Ages. I can’t say that I have a straightforward connection to make between “the passionate intensity of life” Huizinga describes and my own speculations the affective consequences of digital media, but I think there may be something worth getting at. When the world was half a thousand years younger all events had much sharper outlines than now. The distance between sadness and joy, between good and bad fortune, seemed to be much greater than for us; every experience had that degree of directness and absoluteness that joy and sadness still have in the mind of a child. Every even, every deed was defined in given and expressive forms and was in accord with the solemnity of a tight, invariable life style. The great events of human life—birth, marriage, death—by virtue of the sacraments, basked in the radiance of divine mystery. But even the lesser events—a journey, labor, a visit—were accompanied by a multitude of blessings, ceremonies, sayings, and conventions. From the perspective of media ecology, the shift to print as the dominant cultural medium is interpreted as having the effect of tempering the emotional intensity of oral culture and tending instead toward an ironizing effect as it generates a distance between an emotion and its experssion. Digital media curiously scrambles these dynamics by generating an instantaneity of delivery that mimics the immediacy of physical presence. In 2019, I wrote in The New Atlantis about how digital media scrambles the pscyhodynamics (Walter Ong’s phrase) of orality and literacy in often unhelpful ways: “The Inescapable Town Square.” Here’s a bit from that piece: The result is that we combine the weaknesses of each medium while losing their strengths. We are thrust once more into a live, immediate, and active communicative context — the moment regains its heat — but we remain without the non-verbal cues that sustain meaning-making in such contexts. We lose whatever moderating influence the full presence of another human being before us might cast on the passions the moment engendered. This not-altogether-present and not-altogether-absent audience encourages a kind of performative pugilism.To my knowledge, Ivan Illich never met nor corresponded with Hannah Arendt. However, in my efforts to “break bread with the dead,” as Auden once put it, they’re often seated together at the table. In a similarly convivial spirit, here is an excerpt from a recent book by Alissa Wilkinson: I learn from Hannah Arendt that a feast is only possible among friends, or people whose hearts are open to becoming friends. Or you could put it another way: any meal can become a feast when shared with friends engaged in the activity of thinking their way through the world and loving it together. A mere meal is a necessity for life, a fact of being human. But it is transformed into something much more important, something vital to the life of the world, when the people who share the table are engaging in the practices of love and of thinking.Finally, here’s a paragraph from Jacques Ellul’s Propaganda recently highlighted by Jeffrey Bilbro: In individualist theory the individual has eminent value, man himself is the master of his life; in individualist reality each human being is subject to innumerable forces and influences, and is not at all master of his own life. As long as solidly constituted groups exist, those who are integrated into them are subject to them. But at the same time they are protected by them against such external influences as propaganda. An individual can be influenced by forces such as propaganda only when he is cut off from membership in local groups. Because such groups are organic and have a well-structured material, spiritual, and emotional life, they are not easily penetrated by propaganda.Cheers! Hope you are all well, Michael Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. In this installment, I explore a somewhat eccentric frame by which to consider how we relate to our technologies, particularly those we hold close to our bodies. You’ll have to bear through a few paragraphs setting up that frame, but I hope you find it to be a useful exercise. And I welcome your comments below. Ordinarily only paid subscribers can leave comments, but this time around I’m leaving the comments open for all readers. Feel free to chime in. I will say, though, that I may not be able to respond directly to each one. Cheers! Pardon what to some of you will seem like a rather arcane opening to this installment. We’ll be back on more familiar ground soon enough, but I will start us off with a few observations about liturgical practices in religious traditions. A liturgy, incidentally, is a formal and relatively stable set of rites, rituals, and forms that order the public worship of a religious community. There are, for example, many ways to distinguish among the varieties of Christianity in the United States (or globally, for that matter). One might distinguish by region, by doctrine, by ecclesial structure, by the socioeconomic status its members, etc. But one might also place the various strands of the tradition along a liturgical spectrum, a spectrum whose poles are sometimes labeled low church and high church. High church congregations, generally speaking, are characterized by their adherence to formal patterns and rituals. At high church services you would be more likely to observe ritual gestures, such as kneeling, bowing, or crossing oneself as well as ritual speech, such as set prayers, invocations, and responses. High church congregations are also more likely to observe a traditional church calendar and employ traditional vestments and ornamentation. Rituals and formalities of this sort would be mostly absent in low church congregations, which tend to place a higher premium on informality, emotion, and spontaneity of expression. I am painting with a broad brush, but it will serve well enough to set up the point I’m driving at. But one more thing before we get there. What strikes me about certain low church communities is that they sometimes imagine themselves to have no liturgy at all. In some cases, they might even be overtly hostile to the very idea of a liturgy. This is interesting to me because, in practice, it is not that they have no liturgy at all as they imagine—they simply end up with an unacknowledged liturgy of a different sort. Their services also feature predictable patterns and rhythms, as well as common cadences and formulations, even if they are not formally expressed or delineated and although they differ from the patterns and rhythms of high church congregations. It’s not that you get no church calendar, for example, it’s that you end up trading the old ecclesial calendar of holy days and seasons, such as Advent, Epiphany, and Lent, for a more contemporary calendar of national and sentimental holidays, which is to say those that have been most thoroughly commercialized. Now that you’ve borne with this eccentric opening, let me get us to what I hope will be the payoff. In the ecclesial context, this matters because the regular patterns and rhythms of worship, whether recognized as a liturgy or not, are at least as formative (if not more so) as the overt messages presented in a homily, sermon, or lesson, which is where most people assume the real action is. This is so because, as you may have heard it said, the medium is the message. In this case, I take the relevant media to be the embodied ritual forms, the habitual practices, and the material layers of the service of worship. These liturgical forms, acknowledged or unacknowledged, exert a powerful formative influence over time as they write themselves not only upon the mind of the worshipper but upon their bodies and, some might say, hearts. With all of this in mind, then, I would propose that we take a liturgical perspective on our use of technology. (You can imagine the word “liturgical” in quotation marks, if you like.) The point of taking such a perspective is to perceive the formative power of the practices, habits, and rhythms that emerge from our use of certain technologies, hour by hour, day by day, month after month, year in and year out. The underlying idea here is relatively simple but perhaps for that reason easy to forget. We all have certain aspirations about the kind of person we want to be, the kind of relationships we want to enjoy, how we would like our days to be ordered, the sort of society we want to inhabit. These aspirations can be thwarted in any number of ways, of course, and often by forces outside of our control. But I suspect that on occasion our aspirations might also be thwarted by the unnoticed patterns of thought, perception, and action that arise from our technologically mediated liturgies. I don’t call them liturgies as a gimmick, but rather to cast a different, hopefully revealing light on the mundane and commonplace. The image to bear in mind is that of the person who finds themselves handling their smartphone as others might their rosary beads. To properly inventory our technologically mediated liturgies we need to become especially attentive to what our bodies want. After all, the power of a liturgy is that it inscribes itself not only on the mind, but also on the body. In that liminal moment before we have thought about what we are doing but find our bodies already in motion, we can begin to discern the shape of our liturgies. In my waking moments, do I find myself reaching for a device before my eyes have had a chance to open? When I sit down to work, what routines do I find myself engaging? In the company of others, to what is my attention directed? When I as a writer, for example, notice that my hands have moved to open Twitter the very moment I begin to feel my sentence getting stuck, I am under the sway of a technological liturgy. In such moments, I might be tempted to think that my will power has failed me. But from the liturgical perspective I’m exploring here, the problem is not a failure of willpower. Rather, it’s that I’ve trained my will—or, more to the point, I have allowed my will to be trained—to want something contrary to my expressed desire in the moment. One might even argue that this is, in fact, a testament to the power of the will, which is acting in keeping with its training. By what we unthinkingly do, we undermine what we say we want. Say, for example, that I desire to be a more patient person. This is a fine and noble desire. I suspect some of you have desired the same for yourselves at various points. But patience is hard to come by. I find myself lacking patience in the crucial moments regardless of how ardently I have desired it. Why might this be the case? I’m sure there’s more than one answer to this question, but we should at least consider the possibility that my failure to cultivate patience stems from the nature of the technological liturgies that structure my experience. Because speed and efficiency are so often the very reason why I turn to technologies of various sorts, I have been conditioning myself to expect something approaching instantaneity in the way the world responds to my demands. If at every possible point I have adopted tools and devices which promise to make things faster and more efficient, I should not be surprised that I have come to be the sort of person who cannot abide delay and frustration. “The cunning of pedagogic reason,” sociologist Pierre Bourdieu once observed, “lies precisely in the fact that it manages to extort what is essential while seeming to demand the insignificant.” Bourdieu had in mind “the respect for forms and forms of respect which are the most visible and most ‘natural’ manifestation of respect for the established order, or the concessions of politeness, which always contain political concessions.” What I am suggesting is that our technological liturgies function similarly. They, too, manage to extort what is essential while seeming to demand the insignificant. Our technological micro-practices, the movements of our fingers, the gestures of our hands, the posture of our bodies—these seem insignificant until we realize that we are in fact etching the grooves along which our future actions will tend to habitually flow. The point of the exercise is not to divest ourselves of such liturgies altogether. Like certain low church congregations that claim they have no liturgies, we would only deepen the power of the unnoticed patterns shaping our thought and actions. And, more to the point, we would be ceding this power not to the liturgies themselves, but to the interests served by those who have crafted and designed those liturgies. My loneliness is not assuaged by my habitual use of social media. My anxiety is not meaningfully relieved by the habit of consumption engendered by the liturgies crafted for me by Amazon. My health is not necessarily improved by compulsive use of health tracking apps. Indeed, in the latter case, the relevant liturgies will tempt me to reduce health and flourishing to what the apps can measure and quantify. Hannah Arendt once argued that totalitarian regimes succeed, in part, by dislodging or disemedding individuals from their traditional and customary milieus. Individuals who have been so “liberated” are more malleable and subject to new forms of management and control. The consequences of many modern technologies can play out in much the same way. They promise some form of liberation—from the constraints of place, time, community, or even the body itself. Such liberation is often framed as a matter of greater efficiency, convenience, or flexibility. But, to take one example, when someone is freed to work from home, they may find that they can now be expected to work anywhere and at anytime. When older pattern

This is the audio version of the last essay posted a couple of days ago, “What Is To Be Done? — Fragments.” It was a long time between installments of the newsletter, and it has been an even longer stretch since the last audio version. As I note in the audio, my apologies to those of you who primarily rely on the audio version of the essays. I hope to be more consistent on this score moving forward!Incidentally, in recording this installment I noticed a handful of typos in the original essay. I’ve edited these in the web version, but I'm sorry those of you who read the emailed version had to endure them. Obviously, my self-editing was also a bit rusty!One last note, I’ve experimented with a paid-subscribers* discussion thread for this essay. It’s turned out rather well, I think. There’ve been some really insightful comments and questions. So, if you are a paid subscriber, you might want to check that out: Discussion Thread. Cheers, Michael* Note to recent sign-ups: I follow a patronage model. All of the writing is public, there is no paywall for the essays. But I do invite those who value this work to support it as they are able with paid subscriptions. Those who do so, will from time to time have some additional community features come their way. Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. This is the audio version of the last installment, which focused on the Blake Lemoine/LaMDA affair. I argued that while LaMDA is not sentient, applications like it will push us further along toward a digitally re-enchanted world. Also: to keep the essay to a reasonable length I resorted to some longish footnotes in the prior text version. That version also contains links to the various articles and essays I cited throughout the piece. I continue to be somewhat flummoxed about the best way to incorporate the audio and text versions. This is mostly because of how Substack has designed the podcast template. Naturally, it is designed to deliver a podcast rather than text, but I don’t really think of what I do as a podcast. Ordinarily, it is simply an audio version of a textual essay. Interestingly, Substack just launched what, in theory, is an ideal solution: the option to include a simple voiceover of the text, within the text post template. Unfortunately, I don’t think this automatically feeds the audio to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, etc. And, while I don’t think of myself as having a podcast, some of you do access the audio through those services. So, at present, I’ll keep to this somewhat awkward pattern of sending out the text and audio versions separately. Thanks as always to all of you who read, listen, share, and support the newsletter. Nearly three years into this latest iteration of my online work, I am humbled by and grateful for the audience that has gathered around it.Cheers,Michael Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter exploring the relationship between technology and culture. This is what counts as a relatively short post around here, 1800 words or so, about a certain habit of mind that online spaces seem to foster. Almost one year ago, this exchange on Twitter caught my attention, enough so that I took a moment to capture it with a screen shot, thinking I’d go on to write about it at some point. Set aside for a moment whatever your particular thoughts might be on the public debate, if we can call it that, over vaccines, vaccine messaging, vaccine mandates, etc. Instead, consider the form of the claim, specifically the “anti-anti-” framing. I think I first noticed this peculiar way of talking about (or around) an issue circa 2016. In 2020, contemplating the same dynamics, I observed that “social media, perhaps Twitter especially, accelerates both the rate at which we consume information and the rate at which ensuing discussion detaches from the issue at hand, turning into meta-debates about how we respond to the responses of others, etc.” So by the time the Nyhan quote-tweeted Rosen last summer, the “anti-anti-” framing, to my mind, had already entered its mannerist phase. The use of “anti-anti-ad infinitum” is easy to spot, and I’m sure you’ve seen the phrasing deployed on numerous occasions. But the overt use of the “anti-anti-” formulation is just the most obvious manifestation of a more common style of thought, one that I’ve come to refer to as meta-positioning. In the meta-positioning frame of mind, thinking and judgment are displaced by a complex, ever-shifting, and often fraught triangulation based on who holds certain views and how one might be perceived for advocating or failing to advocate for certain views. In one sense, this is not a terribly complex or particularly novel dynamic. Our pursuit of understanding is often an uneasy admixture of the desire to know and the desire to be known as one who knows by those we admire. Unfortunately, social media probably tips the scale in favor of the desire for approval given its rapid-fire feedback mechanisms. Earlier this month, Kevin Baker commented on this same tendency in a recent thread that opened with the following observation, “A lot of irritating, mostly vapid people and ideas were able to build huge followings in 2010s because the people criticizing them were even worse.” Baker goes on to call this “the decade of being anti-anti-” and explains that he felt like he spent “the better part of the decade being enrolled into political and discursive projects that I had serious reservations about because I disagreed [with] their critics more and because I found their behavior reprehensible.” In his view, this is a symptom of the unchecked expansion of the culture wars. Baker again: “This isn't censorship. There weren't really censors. It's more a structural consequence of what happens when an issue gets metabolized by the culture war. There are only two sides and you just have to pick the least bad one.” I’m sympathetic to this view, and would only add that perhaps it is more specifically a symptom of what happens when the digitized culture wars colonize ever greater swaths of our experience. I argued a couple of years ago that just as industrialization gave us industrial warfare, so digitization has given us digitized culture warfare. My argument was pretty straightforward: “Digital media has dramatically enhanced the speed, scale, and power of the tools by which the culture wars are waged and thus transformed their norms, tactics, strategies, psychology, and consequences.” Take a look at the piece if you missed it. I’d say, too, that the meta-positioning habit of mind might also be explained as a consequence of the digitally re-enchanted discursive field. I won’t bog down this post, which I’m hoping to keep relatively brief, with the details of that argument, but here’s the most relevant bit:For my purposes, I’m especially interested in the way that philosopher Charles Taylor incorporates disenchantment theory into his account of modern selfhood. The enchanted world, in Taylor’s view, yielded the experience of a porous, and thus vulnerable self. The disenchanted world yielded an experience of a buffered self, which was sealed off, as the term implies, from beneficent and malignant forces beyond its ken. The porous self depended upon the liturgical and ritual health of the social body for protection against such forces. Heresy was not merely an intellectual problem, but a ritual problem that compromised what we might think of, in these times, as herd immunity to magical and spiritual forces by introducing a dangerous contagion into the social body. The answer to this was not simply reasoned debate but expulsion or perhaps a fiery purgation.Under digitally re-enchanted conditions, policing the bounds of the community appears to overshadow the value of ostensibly objective, civil discourse. In other words, meta-positioning, from this perspective, might just be a matter of making sure you are always playing for the right team, or at least not perceived to be playing for the wrong one. It’s not so much that we have something to say but that we have a social space we want to be seen to occupy. But as I thought about the meta-positioning habit of mind recently, another related set of considerations came to mind, one that is also connected to the digital media ecosystem. As a point of departure, I’d invite you to consider a recent post from Venkatesh Rao about “crisis mindsets.” “As the world has gotten more crisis prone at all levels from personal to geopolitical in the last few years,” Rao explained, “the importance of consciously cultivating a more effective crisis mindset has been increasingly sinking in for me.” I commend the whole post to you, it offers a series of wise and humane observations about how we navigate crisis situations. Rao’s essay crossed my feed while I was drafting this post about meta-positioning, and these lines near the end of the essay caught my attention: “We seem to be entering a historical period where crisis circumstances are more common than normalcy. This means crisis mindsets will increasingly be the default, not flourishing mindsets.”I think this is right, but it also has a curious relationship to the digital media ecosystem. I can imagine someone arguing that genuine crisis circumstances are no more common now than they have ever been but that digital media feeds heighten our awareness of all that is broken in the world and also inaccurately create a sense of ambient crisis. This argument is not altogether wrong. In the digital media ecosystem, we are enveloped by an unprecedented field of near-constant information emanating from the world far and near, and the dynamics of the attention economy also encourage the generation of ambient crisis. But two things can both be true at the same time. It is true, I think, that we are living through a period during which crisis circumstances have become more frequent. This is, in part, because the structures, both social and technological, of the modern world do appear increasingly fragile if not wholly decrepit. It is also true that our media ecosystem heightens our awareness of these crisis circumstances (generating, in turn, a further crisis of the psyche) and that it also generates a field of faux crisis circumstances. Consequently, learning to distinguish between a genuine crisis and a faux crisis will certainly be an essential skill. I would add that it is also critical to distinguish among the array of genuine crisis circumstances that we encounter. Clearly, some will bear directly and unambiguously upon us—a health crisis, say, or a weather emergency. Others will bear on us less directly or acutely, and others still will not bear on us at all. Furthermore, there are those we will be able to address meaningfully through our actions and those we cannot. We should, therefore, learn to apportion our attention and our labors wisely and judiciously. But let’s come back to the habit of mind with which we began. If we are, in fact, inhabiting a media ecosystem that, through sheer scale and ubiquity, heightens our awareness of all that is wrong with the world and overwhelms pre-digital habits of sense-making and crisis-management, then meta-positioning might be more charitably framed as a survival mechanism. As Rao noted, “I have realized there is no such thing as being individually good or bad in a crisis. Humans either deal with crises in effective groups, or not at all.” Just as digital re-enchantment retrieves the communal instinct, so too, perhaps, does the perma-crisis mindset. Recalling Baker’s analysis, we might even say that the digitized culture war layered over the crisis circumstances intensifies the stigma of breaking ranks. There’s one last perspective I’d like to offer on the meta-positioning habit of mind. It also seems to suggest something like a lack of grounding or a certain aimlessness. There is a picture that is informing my thinking here. It is the picture of being adrift in the middle of the ocean with no way to get our bearings. Under these circumstances the best we can ever do is navigate away from some imminent danger, but we can never purposefully aim at a destination. So we find ourselves adrift in the vast digital ocean, and we have no idea what we are doing there or what we should be doing. All we know is that we are caught up in wave after wave of the discourse and the best we can do is to make sure we steer clear of obvious perils and keep our seat on whatever raft we find ourselves in, a raft which might be in shambles but, nonetheless, affords us the best chance of staying afloat. So, maybe the meta-positioning habit of mind is what happens when I have clearer sense of what I am against than what I am for. Or maybe it is better to say that meta-positioning is what happens when we lack meaningful degrees of agency and a

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. I tend to think of my writing as way of clarify my thinking, or, alternatively, of thinking out loud. Often I’m just asking myself, What is going on? That’s the case in this post. There was a techno-cultural pattern I wanted to capture in what follows, but I’m not sure that I’ve done it well enough. So, I’ll submit this for your consideration and critique. You can tell me, if you’re so inclined, whether there’s at least the grain of something helpful here or not. Also, you’ll note that my voice suggests a lingering cold that’s done a bit of a number on me over the past few days, but I hope this is offset by the fact that I’ve finally upgraded my mic and, hopefully, improved the sound quality. Cheers!If asked to define modernity or give its distinctive characteristics, what comes to mind? Maybe the first thing that comes to mind is that such a task is a fool’s errand, and you wouldn’t be wrong. There’s a mountain of books addressing the question, What is or was modernity? And another not insignificant hill of books arguing that, actually, there is or was no such thing, or at least not in the way it has been traditionally understood. Acknowledging as much, perhaps we’d still offer some suggestions. Maybe we’d mention a set of institutions or practices such as representative government or democratic liberalism, scientific inquiry or the authority of reason, the modern university or the free press. Perhaps a set of values comes to mind: individualism, free speech, rule of law, or religious freedom. Or perhaps some more abstract principles, such as instrumental rationality or belief in progress and the superiority of the present over the past. And surely some reference to secularization, markets, and technology would also be made, not to mention colonization and economic exploitation. I won’t attempt to adjudicate those claims or rank them. Also, you’ll have to forgive me if I failed to include you preferred account of modernity; they are many. But I will venture my own tentative and partial theory of the case with a view to possibly illuminating elements of the present state affairs. I’ve been particularly struck of late by the degree to which what I’ll call the myth of the machine became an essential element of the modern or, maybe better, the late modern world. Two clarifications before we proceed. First, I was initially calling this the “myth of neutrality” because I was trying to get at the importance of something like neutral or disinterested or value-free automaticity in various cultural settings. I wasn’t quite happy with neutrality as a way of capturing this pattern, though, and I’ve settled on the myth of the machine because it captures what may be the underlying template that manifests differently across various social spheres. And part of my argument will be that this template takes the automatic, ostensibly value-free operation of a machine as its model. Second, I use the term myth not to suggest something false or duplicitous, but rather to get at the normative and generative power of this template across the social order. That said, let’s move on, starting with some examples of how I see this myth manifesting itself. Objectivity, Impartiality, NeutralityThe myth of the machine underlies a set of three related and interlocking presumptions which characterized modernity: objectivity, impartiality, and neutrality. More specifically, the presumptions that we could have objectively secured knowledge, impartial political and legal institutions, and technologies that were essentially neutral tools but which were ordinarily beneficent. The last of these appears to stand somewhat apart from the first two in that it refers to material culture rather than to what might be taken as more abstract intellectual or moral stances. In truth, however, they are closely related. The more abstract intellectual and institutional pursuits were always sustained by a material infrastructure, and, more importantly, the machine supplied a master template for the organization of human affairs. There are any number of caveats to be made here. This post obviously paints with very broad strokes and deals in generalizations which may not prove useful or hold up under closer scrutiny. Also, I would stress that I take these three manifestations of the myth of the machine to be presumptions, by which I mean that this objectivity, impartiality, and neutrality were never genuinely achieved. The historical reality was always more complicated and, at points, tragic. I suppose the question is whether or not these ideals appeared plausible and desirable to a critical mass of the population, so that they could compel assent and supply some measure of societal cohesion. Additionally, it is obviously true that there were competing metaphors and models on offer, as well as critics of the machine, specifically the industrial machine. The emergence of large industrial technologies certainly strained the social capital of the myth. Furthermore, it is true that by the mid-20th century, a new kind of machine—the cybernetic machine, if you like, or system—comes into the picture. Part of my argument will be that digital technologies seemingly break the myth of the machine, yet not until fairly recently. But the cybernetic machine was still a machine, and it could continue to serve as an exemplar of the underlying pattern: automatic, value-free, self-regulating operation. Now, let me suggest a historical sequence that’s worth noting, although this may be an artifact of my own limited knowledge. The sequence, as I see it, begins in the 17th century with the quest for objectively secured knowledge animating modern philosophy as well as the developments we often gloss as the scientific revolution. Hannah Arendt characterized this quest as the search for an Archimedean point from which to understand the world, an abstract universal position rather than a situated human position. Later in the 18th century, we encounter the emergence of political liberalism, which is to say the pursuit of impartial political and legal institutions or, to put it otherwise, “a ‘machine’ for the adjudication of political differences and conflicts, independently of any faith, creed, or otherwise substantive account of the human good.” Finally, in the 19th century, the hopes associated with these pursuits became explicitly entangled with the development of technology, which was presumed to be a neutral tool easily directed toward the common good. I’m thinking, for example, of the late Leo Marx’s argument about the evolving relationship between progress and technology through the 19th century. “The simple republican formula for generating progress by directing improved technical means to societal ends,” Marx argued, “was imperceptibly transformed into a quite different technocratic commitment to improving ‘technology’ as the basis and the measure of — as all but constituting — the progress of society.”I wrote “explicitly entangled” above because, as I suggested at the outset, I think the entanglement was always implicit. This entanglement is evident in the power of the machine metaphor. The machine becomes the template for a mechanistic view of nature and the human being with attendant developments in a variety of spheres: deism in religion, for example, and the theory of the invisible hand in economics. In both cases, the master metaphor is that of self-regulating machinery. Furthermore, contrasted to the human, the machine appears dispassionate, rational, consistent, efficient, etc. The human was subject to the passions, base motives, errors of judgement, bias, superstition, provincialism, and the like. The more machine-like a person became, the more likely they were to secure objectivity and impartiality. The presumed neutrality of what we today call technology was a material model of these intellectual and moral aspirations. The trajectory of these assumptions leads to technocracy. The technocratic spirit triumphed through at least the mid-twentieth century, and it has remained a powerful force in western culture. I’m tempted to argue, however, that, in the United States at least, the Obama years may come to be seen as its last confident flourish. In any case, the machine supplied a powerful metaphor that worked its way throughout western culture. Another way to frame all of this, of course, is by reference to Jacques Ellul’s preoccupation with what he termed la technique, the imperative to optimize all areas of human experience for efficiency, which he saw as the defining characteristic of modern society. Technique manifests itself in a variety of ways, but one key symptom is the displacement of ends by a fixation on means, so much so that means themselves become ends. The smooth and efficient operation of the system becomes more important than reckoning with which substantive goods should be pursued. Why something ought to be done comes to matter less than that it can be done and faster. The focus drifts toward a consideration of methods, procedures, techniques, and tools and away from a discussion of the goals that ought to be pursued. The Myth of the Machine Breaks DownLet’s revisit the progression I described earlier to see how the myth of the machine begins to break down, and why this is may illuminate the strangeness of our moment. Just as the modern story began with the quest for objectively secured knowledge, this ideal may have been the first to lose its implicit plausibility. Since the late 19th century onward, philosophers, physicists, sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, and historians have, among others, proposed a more complex picture that emphasized the subjective, limited, contingent, situated, and even irrational dimensions of how humans come to know the world. The ideal of objectively secured knowledge became increasingly questionable throughout the 20th century. Some of

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology, culture, and the moral life. In this installment you’ll find the audio version of the previous essay, “The Face Stares Back.” And along with the audio version you’ll also find an assortment of links and resources. Some of you will remember that such links used to be a regular feature of the newsletter. I’ve prioritized the essays, in part because of the information I have on click rates, but I know the links and resources are useful to more than a few of you. Moving forward, I think it makes sense to put out an occasional installment that contains just links and resources (with varying amounts of commentary from me). As always, thanks for reading and/or listening. Links and Resources* Let’s start with a classic paper from 1965 by philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, “Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence.” The paper, prepared for the RAND Corporation, opens with a long epigraph from the 17th-century polymath Blaise Pascal on the difference between the mathematical mind and the perceptive mind. * On “The Tyranny of Time”: “The more we synchronize ourselves with the time in clocks, the more we fall out of sync with our own bodies and the world around us.” More: “The Western separation of clock time from the rhythms of nature helped imperialists establish superiority over other cultures.”* Relatedly, a well-documented case against Daylight Saving Time: “Farmers, Physiologists, and Daylight Saving Time”: “Fundamentally, their perspective is that we tend to do well when our body clock and social clock—the official time in our time zone—are in synch. That is, when noon on the social clock coincides with solar noon, the moment when the Sun reaches its highest point in the sky where we are. If the two clocks diverge, trouble ensues. Startling evidence for this has come from recent findings in geographical epidemiology—specifically, from mapping health outcomes within time zones.”* Jasmine McNealy on “Framing and Language of Ethics: Technology, Persuasion, and Cultural Context.” * Interesting forthcoming book by Kevin Driscoll: The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media.* Great piece on Jacques Ellul by Samuel Matlack at The New Atlantis, “How Tech Despair Can Set You Free”: “But Ellul rejects it. He refuses to offer a prescription for social reform. He meticulously and often tediously presents a problem — but not a solution of the kind we expect. This is because he believed that the usual approach offers a false picture of human agency. It exaggerates our ability to plan and execute change to our fundamental social structures. It is utopian. To arrive at an honest view of human freedom, responsibility, and action, he believed, we must confront the fact that we are constrained in more ways than we like to think. Technique, says Ellul, is society’s tightest constraint on us, and we must feel the totality of its grip in order to find the freedom to act.”* Evan Selinger on “The Gospel of the Metaverse.”* Ryan Calo on “Modeling Through”: “The prospect that economic, physical, and even social forces could be modeled by machines confronts policymakers with a paradox. Society may expect policymakers to avail themselves of techniques already usefully deployed in other sectors, especially where statutes or executive orders require the agency to anticipate the impact of new rules on particular values. At the same time, “modeling through” holds novel perils that policymakers may be ill equipped to address. Concerns include privacy, brittleness, and automation bias, all of which law and technology scholars are keenly aware. They also include the extension and deepening of the quantifying turn in governance, a process that obscures normative judgments and recognizes only that which the machines can see. The water may be warm, but there are sharks in it.”* “Why Christopher Alexander Still Matters”: “The places we love, the places that are most successful and most alive, have a wholeness about them that is lacking in too many contemporary environments, Alexander observed. This problem stems, he thought, from a deep misconception of what design really is, and what planning is. It is not “creating from nothing”—or from our own mental abstractions—but rather, transforming existing wholes into new ones, and using our mental processes and our abstractions to guide this natural life-supporting process.” * An interview with philosopher Shannon Vallor: “Re-envisioning Ethics in the Information Age”: “Instead of using the machines to liberate and enlarge our own lives, we are increasingly being asked to twist, to transform, and to constrain ourselves in order to strengthen the reach and power of the machines that we increasingly use to deliver our public services, to make the large-scale decisions that are needed in the financial realm, in health care, or in transportation. We are building a society where the control surfaces are increasingly automated systems and then we are asking humans to restrict their thinking patterns and to reshape their thinking patterns in ways that are amenable to this system. So what I wanted to do was to really reclaim some of the literature that described that process in the 20th century—from folks like Jacques Ellul, for example, or Herbert Marcuse—and then really talk about how this is happening to us today in the era of artificial intelligence and what we can do about it.”* From Lance Strate in 2008: “Studying Media AS Media: McLuhan and the Media Ecology Approach.” * Japan’s museum of rocks that look like faces.* I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Katherine Dee for her podcast, which you can listen to here.* I’ll leave you with an arresting line from Simone Weil’s notebooks: “You could not have wished to be born at a better time than this, when everything is lost.” Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. The pace of the newsletter has been slow of late, which I regret, but I trust it will pick up just a touch in the coming weeks (also please forgive me if you’ve been in touch over the past month or so and haven’t heard back). For starters, I’ll follow up this installment shortly with another that will include some links and resources. In this installment, I’m thinking about attention again, but from a slightly different perspective—how do we become the objects of the attention for others? If you’re a recent subscriber, I’ll note that attention is recurring theme in my writing, although it may be awhile before I revisit it again (but don’t hold me to that). As per usual, this is an exercise in thinking out loud, which seeks to clarify some aspect of our experience with technology and explore its meaning. I hope you find it useful. Finally, I’m playing with formatting again, driven chiefly by the fact that this is a hybrid text meant to be both read and/or listened to in the audio version. So you’ll note my use of bracketed in-text excursuses in this installment. If it degrades your reading or listening, feel free to let me know. Objects of Attention A recent email exchange with Dr. Andreas Mayert got me thinking about attention from yet another angle. Ordinarily, I think about attention as something I have, or, as I suggested in a recent installment, something I do. I give my attention to things out there in the world, or, alternatively, I attend to the world out there. Regardless of how we formulate it, what I am imagining in these cases is how attention flows outward from me, the subject, to some object in the world. And there’s much to consider from that perspective: how we direct our attention, for example, or how objects in the world beckon and reward our attention. But, as Dr. Mayert suggested to me, it’s also worth considering how attention flows in the opposite direction. That is to say, considering not the attention I give, but the attention that bears down on me. [First excursus: The case of attending to myself is an interesting one given this way of framing attention as both incoming and outgoing. If I attend to my own body—by minding my breathing, for example—I’d say that my attention still feels to me as if it is going outward before then focusing inward. It’s the mind’s gaze upon the body. But it’s a bit different if I’m trying to attend to my own thoughts. In this case I find it difficult to assign directionality to my attention. Moreover, it seems to me that the particular sense I am using to attend to the world matters in this regard, too. For example, closing my eyes seems to change the sense that my attention is flowing out from my body. As I listen while my eyes are shut, I have the sense that sounds are spatially located, to my left rather than to my right, but also that the sound is coming to me. I’m reminded, too, of the ancient understanding of vision, which conceived of sight as a ray emanating from the eye to make contact with the world. The significance of these subtle shifts in how we perceive the world and how media relate to perception should not be underestimated.]There are several ways of thinking about where this attention that might fix on us as its object originates. We can consider, for example, how we become an object of attention for large, impersonal entities like the state or a corporation. Or we can contemplate how we become the object of attention for another person—legibility in the former case and the gaze in the latter. There are any number of other possibilities and variations within them, but given my exchange with Mayert I found myself considering what happens when a machine pays attention to us. By “machine” in this case, I mean any of the various assemblages of devices, sensors, and programs through which data is gathered about us and interpretations are extrapolated from that data, interpretations which purport to reveal something about us that we ourselves may not otherwise recognize or wish to disclose. I am, to be honest, hesitant to say that the machine (or program or app, etc.) pays attention to us or, much less, attends to us. I suppose it is better to say that the machine mediates the attention of others. But there is something about the nature of that mediation that transforms the experience of being the object of another’s attention to such a degree that it may be inadequate to speak merely of the attention of another. By comparison, if I discover that someone is using a pair of binoculars to watch me at a distance, I would still say, with some unease to be sure, that it is the person and not the binoculars that are attending to me although of course their gaze is mediated by the binoculars. If I’m being watched on a recording of cctv footage, even though someone is attending to me asynchronously through the mediation of the camera, I’d still say that it is the person is paying attention to me although I might hesitate to say that it is me they are paying attention to. However, I’m less confident of putting it quite that way when, say, data about me is being captured, interpreted, and filtered to another who attends to me through that data and its interpretation. It does seem as if the primary work of attention, so to speak, is done not by the person but the machine, and this qualitatively changes the experience of being noted and attended to. Perhaps one way to say this is that when we are attended to by (or through) a machine we too readily become merely an object of analysis stripped of depth and agency, whereas when we are attended to more directly, although not necessarily in unmediated fashion, it may be harder—but not impossible, of course—to be similarly objectified.I am reminded, for example, of the unnamed protagonist of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, a priest known better for his insobriety than his piety, who, while being jailed alongside one of his tormentors, thinks to himself, “When you visualized a man or woman carefully, you could always begin to feel pity … that was a quality God’s image carried with it … when you saw the lines at the corners of the eyes, the shape of the mouth, how the hair grew, it was impossible to hate.” There’s much that may discourage us from attending to another in this way, but the mediation of the machine seems to remove the possibility altogether. I am reminded of Clive Thompson’s intriguing analysis of captcha images, that grid of images that sometimes appears when you are logging in to a site and from which you are to select squares that contain things like buses or traffic lights. Thompson set out to understand why he found captcha images “overwhelmingly depressing.” After considering several factors, here’s what he concluded: “They weren’t taken by humans, and they weren’t taken for humans. They are by AI, for AI. They thus lack any sense of human composition or human audience. They are creations of utterly bloodless industrial logic. Google’s CAPTCHA images demand you to look at the world the way an AI does.”The uncanny and possibly depressing character of the captcha images is, in Thompson’s compelling argument, a function of being forced to see the world from a non-human perspective. I’d suggest that some analogous unease emerges when we know ourselves to be perceived or attended to by a non-human agent, something that now happens routinely. In one way or another we are the objects of attention for traffic light cameras, smart speakers, sentiment analysis tools, biometric sensors, doorbell cameras, proctoring software, on-the-job motion detectors, and algorithms used to ostensibly discern our credit worthiness, suitability for a job, or proclivity to commit a crime. The list could go on and on. We navigate a field in which we are just as likely to be scanned, analyzed, and interpreted by a machine as we are to enjoy the undisturbed attention of another human being. Digital Impression Management To explore these matters a bit more concretely, I’ll finally come to the subject of my exchange with Dr. Mayert, which was a study he conducted examining how some people experience the attention of a machine bearing down on them.Mayert’s research examined how employees reasoned about systems, increasingly used in the hiring process, which promise to “create complex personality profiles from superficially innocuous individual social media profiles.” You’ll find an interview with Dr. Mayert and a link to the study, both in German, here, and you can use your online translation tool of choice if, like me, you’re not up on your German. With permission, I’ll share portions of what Mayert discussed in our email exchange. The findings were interesting. On the one hand, Mayert found that “employees have no problem at all with companies taking a superficial look at their social media profiles to observe what is in any case only a mask in Goffman's sense.” Erving Goffman, you may recall, was a mid-twentieth century sociologist, who, in The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life, developed a dramaturgical model of human identity and social interactions. The basic idea is that we can understand social interactions by analogy to stage performance. When we’re “on stage,” we’re involved in the work of “impression management.” Which is to say that we carefully manage how we are perceived by controlling the impressions we’re giving off. (Incidentally, media theorist Joshua Meyrowitz usefully put Goffman’s work in conversation with McLuhan’s in No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior, an underrated work of media theory published in 1986.) So the idea here is that social media platforms are Goffmanesque stages, and, after we came to terms with context collapse, we figured out how to manage the impressions given off by our profiles. Indeed, from this perspective we might say that social media just made explicit (

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter that is ostensibly about technology and culture but more like my effort to make some sense of the world taking shape around us. For many of you, this will be the first installment to hit your inbox—welcome aboard. And my thanks to those of you who share the newsletter with others and speak well of it. If you are new to the Convivial Society, please feel free to read this orientation to new readers that I posted a few months ago. 0. Attention discourse is my term for the proliferation of articles, essays, books, and op-eds about attention and distraction in the age of digital media. I don’t mean the label pejoratively. I’ve made my own contributions to the genre, in this newsletter and elsewhere, and as recently as May of last year. In fact, I tend to think that attention discourse circles around immensely important issues we should all think about more deliberately. So, here then, is yet another entry for the attention files presented as a numbered list of loosely related observations for you consideration, a form in which I like to occasionally indulge and which I hope you find suggestive and generative. 1. I take Nick Carr’s 2008 piece in The Atlantic, “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”, to be the ur-text of this most recent wave of attention discourse. If that’s fair, then attention and distraction have been the subject of intermittent public debate for nearly fifteen years, but this sustained focus appears to have yielded little by way of improving our situation. I say the “the most recent wave” because attention discourse has a history that pre-dates the digital age. The first wave of attention discourse can be dated back to the mid-nineteenth century, as historian Jonathan Crary has argued at length, especially in his 1999 book, Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture. “For it is in the late nineteenth century,” Crary observed, within the human sciences and particularly the nascent field of scientific psychology, that the problem of attention becomes a fundamental issue. It was a problem whose centrality was directly related to the emergence of a social, urban, psychic, and industrial field increasingly saturated with sensory input. Inattention, especially within the context of new forms of large-scale industrialized production, began to be treated as a danger and a serious problem, even though it was often the very modernized arrangements of labor that produced inattention. It is possible to see one crucial aspect of modernity as an ongoing crisis of attentiveness, in which the changing configurations of capitalism continually push attention and distraction to new limits and thresholds, with an endless sequence of new products, sources of stimulation, and streams of information, and then respond with new methods of managing and regulating perception […] But at the same time, attention, as a historical problem, is not reducible to the strategies of social discipline. As I shall argue, the articulation of a subject in terms of attentive capacities simultaneously disclosed a subject incapable of conforming to such disciplinary imperatives.” Many of the lineaments of contemporary attention discourse are already evident in Crary’s description of its 19th century antecedents. 2. One reaction to learning that modern day attention discourse has longstanding antecedents would be to dismiss contemporary criticisms of the digital attention economy. The logic of such dismissals is not unlike that of the tale of Chicken Little. Someone is always proclaiming that the sky is falling, but the sky never falls. This is, in fact, a recurring trope in the wider public debate about technology. The seeming absurdity of some 19th-century pundit decrying the allegedly demoralizing consequences of the novel is somehow enough to ward off modern day critiques of emerging technologies. Interestingly, however, it’s often the case that the antecedents don’t take us back indefinitely into the human past. Rather, they often have a curiously consistent point of origin: somewhere in the mid- to late-nineteenth century. It’s almost as if some radical techno-economic re-ordering of society had occurred, generating for the first time a techno-social environment which was, in some respects at least, inhospitable to the embodied human person. That the consequences linger and remain largely unresolved, or that new and intensified iterations of the older disruptions yield similar expressions of distress should not be surprising. 3. Simone Weil, writing in Oppression and Liberty (published posthumously in 1955): “Never has the individual been so completely delivered up to a blind collectivity, and never have men been less capable, not only of subordinating their actions to their thoughts, but even of thinking. Such terms as oppressors and oppressed, the idea of classes—all that sort of thing is near to losing all meaning, so obvious are the impotence and distress of all men in the face of the social machine, which has become a machine for breaking hearts and crushing spirits, a machine for manufacturing irresponsibility, stupidity, corruption, slackness and, above all, dizziness. The reason for this painful state of affairs is perfectly clear. We are living in a world in which nothing is made to man’s measure; there exists a monstrous discrepancy between man’s body, man’s mind and the things which at present time constitute the elements of human existence; everything is in disequilibrium […] This disequilibrium is essentially a matter of quantity. Quantity is changed into quality, as Hegel said, and in particular a mere difference in quantity is sufficient to change what is human in to what is inhuman. From the abstract point of view quantities are immaterial, since you can arbitrarily change the unit of measurement; but from the concrete point of view certain units of measurement are given and have hitherto remained invariable, such as the human body, human life, the year, the day, the average quickness of human thought. Present-day life is not organized on the scale of all these things; it has been transported into an altogether different order of magnitude, as though men were trying to raise it to the level of the forces outside of nature while neglecting to take his own nature into account.”4. Nicholas Carr began his 2008 article with a bit of self-disclosure, which I suspect now sounds pretty familiar to most of us if it didn’t already then. Here’s what he reported: Over the past few years I’ve had an uncomfortable sense that someone, or something, has been tinkering with my brain, remapping the neural circuitry, reprogramming the memory. My mind isn’t going—so far as I can tell—but it’s changing. I’m not thinking the way I used to think. I can feel it most strongly when I’m reading. Immersing myself in a book or a lengthy article used to be easy. My mind would get caught up in the narrative or the turns of the argument, and I’d spend hours strolling through long stretches of prose. That’s rarely the case anymore. Now my concentration often starts to drift after two or three pages. I get fidgety, lose the thread, begin looking for something else to do. I feel as if I’m always dragging my wayward brain back to the text. The deep reading that used to come naturally has become a struggle.At the time, it certainly resonated with me, and what may be most worth noting about this today is that Carr, and those who are roughly his contemporaries in age, were in the position of living before and after the rise of the commercial internet and thus had a point of experiential contrast to emerging digital culture. 5. I thought of this paragraph recently while I was reading the transcript of Sean Illing’s interview with Johann Hari about his new book, Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention—And How to Think Deeply Again. Not long after reading the text of Illing’s interview, I also read the transcript of his conversation with Ezra Klein, which you can read or listen to here. I’m taking these two conversations as an occasion to reflect again on attention, for it’s own sake but also as an indicator of larger patterns in our techno-social milieu. I’ll dip into both conversations to frame my own discussion, and, as you’ll see, my interest isn’t to criticize Hari’s argument but rather to pose some questions and take it as a point of departure. Hari, it turns out, is, like me, in his early-40s. So we, too, lived a substantial chunk of time in the pre-commercial internet era. And, like Carr, Hari opens his conversation with Illing by reporting on his own experience: I noticed that with each year that passed, it felt like my own attention was getting worse. It felt like things that require a deep focus, like reading a book, or watching long films, were getting more and more like running up and down an escalator. I could do them, but they were getting harder and harder. And I felt like I could see this happening to most of the people I knew.But, as the title of his book suggests, Hari believes that this was not just something that has happened but something that was done to him. “We need to understand that our attention did not collapse,” he tells Illing, “our attention has been stolen from us by these very big forces. And that requires us to think very differently about our attention problems.”Like many others before him, Hari argues that these “big forces” are the tech companies, who have designed their technologies with a view to capturing as much of our attention as possible. In his view, we live in a technological environment that is inhospitable to the cultivation of attentiveness. And, to be sure, I think this is basically right, as far as it goes. This is not a wholly novel development, as we noted at the outset, even if its scope and scale have expanded and intensified. 6. There’s another dimension to this that’s worth considering because it is often obscured by the way we tend to

As promised, here is the audio version of the last installment, “The Dream of Virtual Reality.” To those of you who find the audio version helpful, thank you for your patience! And while I’m at it, let me pass along a few links, a couple of which are directly related to this installment. LinksJust after I initially posted “The Dream of Virtual Reality,” Evan Selinger reached out with a link to his interview of David Chalmers about Reality+. I confess to thinking that I might have been a bit uncharitable in taking Chalmers’s comments in a media piece as the basis of my critique, but after reading the interview I now feel just fine about it. And, apropos my comments about science fiction, here’s a discussion between philosophers Nigel Warburton and Eric Schwitzgebel about the relationship between philosophy and science fiction. It revolves around a discussion of five specific sci-fi texts Schwitzgebel recommends. Unrelated to virtual reality, let me pass along this essay by Meghan O’Gieblyn: “Routine Maintenance: Embracing habit in an automated world.” It is an excellent reflection on the virtues of habit. It’s one of those essays I wish I had written. In fact, I have a draft of a future installment that I had titled “From Habit to Habit.” It will aim at something a bit different, but I’m sure that it will now incorporate some of what O’Gieblyn has written. You may also recognize O’Gieblyn as the author of God, Human, Animal, Machine, which I’ve got on my nightstand and will be reading soon. In a brief discussion of Elon Musk’s Neuralink in his newsletter New World Same Humans, David Mattin makes the following observation: A great schism is emerging. It’s between those who believe we should use technology to transcend all known human limits even if that comes at the expense of our humanity itself, and those keen to hang on to recognisably human forms of life and modes of consciousness. It may be a while yet until that conflict becomes a practical and widespread reality. But as Neuralink prepares for its first human trials, we can hear that moment edging closer.I think this is basically right, and I’ve been circling around this point for quite some time. But I would put the matter a bit differently: I’m not so sure that it will be a while until that conflict becomes a practical and widespread reality. I think it has been with us for quite some time, and, in my less hopeful moments, I tend to think that we have already crossed some critical threshold. As I’ve put it elsewhere, transhumanism is the default eschatology of the modern technological project. PodcastsLastly, I’ve been neglecting to pass along links to some podcasts I’ve been on recently. Let me fill you in on a couple of these. Last fall, I had the pleasure of talking to historian Lee Vinsel for his new podcast, People and Things. We talked mostly Illich and it was a great conversation. I commend Vinsel’s whole catalog to you. Peruse at your leisure. Certainly be sure to catch the inaugural episode with historian Ruth Schwartz Cowan, the author of one of the classic texts in the history of technology, More Work For Mother: The Ironies Of Household Technology From The Open Hearth To The Microwave. And just today my conversation with the Irish economist David McWilliams was posted. We talked mostly about the so-called meta verse, and while we focused on my early “Notes From the Metaverse,” it also pairs nicely with the latest installment. My thanks to David and his team for their conviviality. And to the new set of readers from Ireland, the UK, and beyond—welcome!PostscriptI can not neglect to mention that it was brought to my attention that the promo video for Facebook’s VR platform, Horizons, from which I took a screenshot for the essay, has a comical disclaimer near the bottom of the opening shot. As philosopher Ariel Guersenzvaig noted on Twitter, “‘Virtual reality is genuine reality’? Be that as it may, the VR footage is not genuine VR footage!” Get full access to The Convivial Society at theconvivialsociety.substack.com/subscribe