The Myth of the Machine

Description

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. I tend to think of my writing as way of clarify my thinking, or, alternatively, of thinking out loud. Often I’m just asking myself, What is going on? That’s the case in this post. There was a techno-cultural pattern I wanted to capture in what follows, but I’m not sure that I’ve done it well enough. So, I’ll submit this for your consideration and critique. You can tell me, if you’re so inclined, whether there’s at least the grain of something helpful here or not. Also, you’ll note that my voice suggests a lingering cold that’s done a bit of a number on me over the past few days, but I hope this is offset by the fact that I’ve finally upgraded my mic and, hopefully, improved the sound quality. Cheers!

If asked to define modernity or give its distinctive characteristics, what comes to mind? Maybe the first thing that comes to mind is that such a task is a fool’s errand, and you wouldn’t be wrong. There’s a mountain of books addressing the question, What is or was modernity? And another not insignificant hill of books arguing that, actually, there is or was no such thing, or at least not in the way it has been traditionally understood.

Acknowledging as much, perhaps we’d still offer some suggestions. Maybe we’d mention a set of institutions or practices such as representative government or democratic liberalism, scientific inquiry or the authority of reason, the modern university or the free press. Perhaps a set of values comes to mind: individualism, free speech, rule of law, or religious freedom. Or perhaps some more abstract principles, such as instrumental rationality or belief in progress and the superiority of the present over the past. And surely some reference to secularization, markets, and technology would also be made, not to mention colonization and economic exploitation.

I won’t attempt to adjudicate those claims or rank them. Also, you’ll have to forgive me if I failed to include you preferred account of modernity; they are many. But I will venture my own tentative and partial theory of the case with a view to possibly illuminating elements of the present state affairs. I’ve been particularly struck of late by the degree to which what I’ll call the myth of the machine became an essential element of the modern or, maybe better, the late modern world. Two clarifications before we proceed. First, I was initially calling this the “myth of neutrality” because I was trying to get at the importance of something like neutral or disinterested or value-free automaticity in various cultural settings. I wasn’t quite happy with neutrality as a way of capturing this pattern, though, and I’ve settled on the myth of the machine because it captures what may be the underlying template that manifests differently across various social spheres. And part of my argument will be that this template takes the automatic, ostensibly value-free operation of a machine as its model. Second, I use the term myth not to suggest something false or duplicitous, but rather to get at the normative and generative power of this template across the social order. That said, let’s move on, starting with some examples of how I see this myth manifesting itself.

Objectivity, Impartiality, Neutrality

The myth of the machine underlies a set of three related and interlocking presumptions which characterized modernity: objectivity, impartiality, and neutrality. More specifically, the presumptions that we could have objectively secured knowledge, impartial political and legal institutions, and technologies that were essentially neutral tools but which were ordinarily beneficent. The last of these appears to stand somewhat apart from the first two in that it refers to material culture rather than to what might be taken as more abstract intellectual or moral stances. In truth, however, they are closely related. The more abstract intellectual and institutional pursuits were always sustained by a material infrastructure, and, more importantly, the machine supplied a master template for the organization of human affairs.

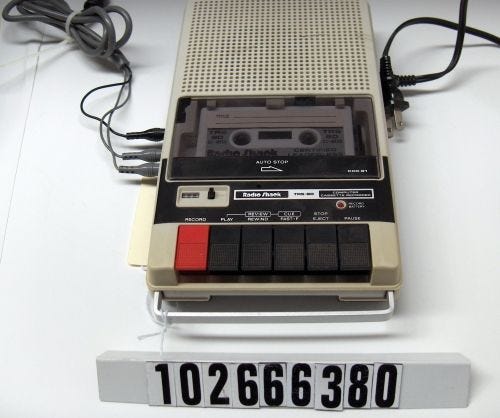

There are any number of caveats to be made here. This post obviously paints with very broad strokes and deals in generalizations which may not prove useful or hold up under closer scrutiny. Also, I would stress that I take these three manifestations of the myth of the machine to be presumptions, by which I mean that this objectivity, impartiality, and neutrality were never genuinely achieved. The historical reality was always more complicated and, at points, tragic. I suppose the question is whether or not these ideals appeared plausible and desirable to a critical mass of the population, so that they could compel assent and supply some measure of societal cohesion. Additionally, it is obviously true that there were competing metaphors and models on offer, as well as critics of the machine, specifically the industrial machine. The emergence of large industrial technologies certainly strained the social capital of the myth. Furthermore, it is true that by the mid-20th century, a new kind of machine—the cybernetic machine, if you like, or system—comes into the picture. Part of my argument will be that digital technologies seemingly break the myth of the machine, yet not until fairly recently. But the cybernetic machine was still a machine, and it could continue to serve as an exemplar of the underlying pattern: automatic, value-free, self-regulating operation.

Now, let me suggest a historical sequence that’s worth noting, although this may be an artifact of my own limited knowledge. The sequence, as I see it, begins in the 17th century with the quest for objectively secured knowledge animating modern philosophy as well as the developments we often gloss as the scientific revolution. Hannah Arendt characterized this quest as the search for an Archimedean point from which to understand the world, an abstract universal position rather than a situated human position. Later in the 18th century, we encounter the emergence of political liberalism, which is to say the pursuit of impartial political and legal institutions or, to put it otherwise, “a ‘machine’ for the adjudication of political differences and conflicts, independently of any faith, creed, or otherwise substantive account of the human good.” Finally, in the 19th century, the hopes associated with these pursuits became explicitly entangled with the development of technology, which was presumed to be a neutral tool easily directed toward the common good. I’m thinking, for example, of the late Leo Marx’s argument about the evolving relationship between progress and technology through the 19th century. “The simple republican formula for generating progress by directing improved technical means to societal ends,” Marx argued, “was imperceptibly transformed into a quite different technocratic commitment to improving ‘technology’ as the basis and the measure of — as all but constituting — the progress of society.”

I wrote “explicitly entangled” above because, as I suggested at the outset, I think the entanglement was always implicit. This entanglement is evident in the power of the machine metaphor. The machine becomes the template for a mechanistic view of nature and the human being with attendant developments in a variety of spheres: deism in religion, for example, and the theory of the invisible hand in economics. In both cases, the master metaphor is that of self-regulating machinery. Furthermore, contrasted to the human, the machine appears dispassionate, rational, consistent, efficient, etc. The human was subject to the passions, base motives, errors of judgement, bias, superstition, provincialism, and the like. The more machine-like a person became, the more likely they were to secure objectivity and impartiality. The presumed neutrality of what we today call technology was a material model of these intellectual and moral aspirations. The trajectory of these assumptions leads to technocracy. The technocratic spirit triumphed through at least the mid-twentieth century, and it has remained a powerful force in western culture. I’m tempted to argue, however, that, in the United States at least, the Obama years may come to be seen as its last confident flourish. In any case, the machine supplied a powerful metaphor that worked its way throughout western culture.

Another way to frame all of this, of course, is by reference to Jacques Ellul’s preoccupation with what he termed la technique, the imperative to optimize all areas of human experience for efficiency, which he saw as the defining characteristic of modern society. Technique manifests itself in a variety of ways, but one key symptom is the displacement of ends by a fixation on means, so much so that means themselves become ends. The smooth and efficient operation of the system becomes more important than reckoning with which substantive goods should be pursued. Why something ought to be done comes to matter less than that it can be done and faster. The focus drifts toward a consideration of methods, procedures, techniques, and tools and away from a discussion of the goals that ought to be pursued.

The Myth of the Machine Breaks Down

Let’s revisit the progression I described earlier to see how the myth of the machine begins to break down, and why this is may illuminate the strangeness of our moment. Just as the modern story began with the quest for objectively secured knowledge, this ideal may have been the first to lose its implicit plausibility. Since the late 19th century onward, philosophers, physicists, sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, and historians have, among others, proposed a more complex picture that emphasized the subjective, limited, contingent, situated, and even irrational dimensions of how humans com