The Uncanny Gaze of the Machine

Description

Welcome to the Convivial Society, a newsletter about technology and culture. The pace of the newsletter has been slow of late, which I regret, but I trust it will pick up just a touch in the coming weeks (also please forgive me if you’ve been in touch over the past month or so and haven’t heard back). For starters, I’ll follow up this installment shortly with another that will include some links and resources. In this installment, I’m thinking about attention again, but from a slightly different perspective—how do we become the objects of the attention for others? If you’re a recent subscriber, I’ll note that attention is recurring theme in my writing, although it may be awhile before I revisit it again (but don’t hold me to that). As per usual, this is an exercise in thinking out loud, which seeks to clarify some aspect of our experience with technology and explore its meaning. I hope you find it useful. Finally, I’m playing with formatting again, driven chiefly by the fact that this is a hybrid text meant to be both read and/or listened to in the audio version. So you’ll note my use of bracketed in-text excursuses in this installment. If it degrades your reading or listening, feel free to let me know.

Objects of Attention

A recent email exchange with Dr. Andreas Mayert got me thinking about attention from yet another angle. Ordinarily, I think about attention as something I have, or, as I suggested in a recent installment, something I do. I give my attention to things out there in the world, or, alternatively, I attend to the world out there. Regardless of how we formulate it, what I am imagining in these cases is how attention flows outward from me, the subject, to some object in the world. And there’s much to consider from that perspective: how we direct our attention, for example, or how objects in the world beckon and reward our attention. But, as Dr. Mayert suggested to me, it’s also worth considering how attention flows in the opposite direction. That is to say, considering not the attention I give, but the attention that bears down on me.

[First excursus: The case of attending to myself is an interesting one given this way of framing attention as both incoming and outgoing. If I attend to my own body—by minding my breathing, for example—I’d say that my attention still feels to me as if it is going outward before then focusing inward. It’s the mind’s gaze upon the body. But it’s a bit different if I’m trying to attend to my own thoughts. In this case I find it difficult to assign directionality to my attention. Moreover, it seems to me that the particular sense I am using to attend to the world matters in this regard, too. For example, closing my eyes seems to change the sense that my attention is flowing out from my body. As I listen while my eyes are shut, I have the sense that sounds are spatially located, to my left rather than to my right, but also that the sound is coming to me. I’m reminded, too, of the ancient understanding of vision, which conceived of sight as a ray emanating from the eye to make contact with the world. The significance of these subtle shifts in how we perceive the world and how media relate to perception should not be underestimated.]

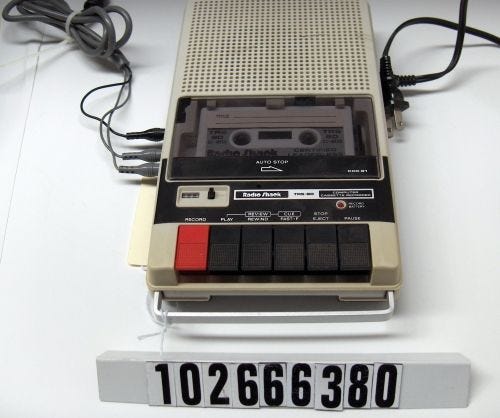

There are several ways of thinking about where this attention that might fix on us as its object originates. We can consider, for example, how we become an object of attention for large, impersonal entities like the state or a corporation. Or we can contemplate how we become the object of attention for another person—legibility in the former case and the gaze in the latter. There are any number of other possibilities and variations within them, but given my exchange with Mayert I found myself considering what happens when a machine pays attention to us. By “machine” in this case, I mean any of the various assemblages of devices, sensors, and programs through which data is gathered about us and interpretations are extrapolated from that data, interpretations which purport to reveal something about us that we ourselves may not otherwise recognize or wish to disclose.

I am, to be honest, hesitant to say that the machine (or program or app, etc.) pays attention to us or, much less, attends to us. I suppose it is better to say that the machine mediates the attention of others. But there is something about the nature of that mediation that transforms the experience of being the object of another’s attention to such a degree that it may be inadequate to speak merely of the attention of another. By comparison, if I discover that someone is using a pair of binoculars to watch me at a distance, I would still say, with some unease to be sure, that it is the person and not the binoculars that are attending to me although of course their gaze is mediated by the binoculars. If I’m being watched on a recording of cctv footage, even though someone is attending to me asynchronously through the mediation of the camera, I’d still say that it is the person is paying attention to me although I might hesitate to say that it is me they are paying attention to.

However, I’m less confident of putting it quite that way when, say, data about me is being captured, interpreted, and filtered to another who attends to me through that data and its interpretation. It does seem as if the primary work of attention, so to speak, is done not by the person but the machine, and this qualitatively changes the experience of being noted and attended to. Perhaps one way to say this is that when we are attended to by (or through) a machine we too readily become merely an object of analysis stripped of depth and agency, whereas when we are attended to more directly, although not necessarily in unmediated fashion, it may be harder—but not impossible, of course—to be similarly objectified.

I am reminded, for example, of the unnamed protagonist of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, a priest known better for his insobriety than his piety, who, while being jailed alongside one of his tormentors, thinks to himself, “When you visualized a man or woman carefully, you could always begin to feel pity … that was a quality God’s image carried with it … when you saw the lines at the corners of the eyes, the shape of the mouth, how the hair grew, it was impossible to hate.” There’s much that may discourage us from attending to another in this way, but the mediation of the machine seems to remove the possibility altogether.

I am reminded of Clive Thompson’s intriguing analysis of captcha images, that grid of images that sometimes appears when you are logging in to a site and from which you are to select squares that contain things like buses or traffic lights. Thompson set out to understand why he found captcha images “overwhelmingly depressing.” After considering several factors, here’s what he concluded:

“They weren’t taken by humans, and they weren’t taken for humans. They are by AI, for AI. They thus lack any sense of human composition or human audience. They are creations of utterly bloodless industrial logic. Google’s CAPTCHA images demand you to look at the world the way an AI does.”

The uncanny and possibly depressing character of the captcha images is, in Thompson’s compelling argument, a function of being forced to see the world from a non-human perspective. I’d suggest that some analogous unease emerges when we know ourselves to be perceived or attended to by a non-human agent, something that now happens routinely. In one way or another we are the objects of attention for traffic light cameras, smart speakers, sentiment analysis tools, biometric sensors, doorbell cameras, proctoring software, on-the-job motion detectors, and algorithms used to ostensibly discern our credit worthiness, suitability for a job, or proclivity to commit a crime. The list could go on and on. We navigate a field in which we are just as likely to be scanned, analyzed, and interpreted by a machine as we are to enjoy the undisturbed attention of another human being.

Digital Impression Management

To explore these matters a bit more concretely, I’ll finally come to the subject of my exchange with Dr. Mayert, which was a study he conducted examining how some people experience the attention of a machine bearing down on them.

Mayert’s research examined how employees reasoned about systems, increasingly used in the hiring process, which promise to “create complex personality profiles from superficially innocuous individual social media profiles.” You’ll find an interview with Dr. Mayert and a link to the study, both in German, here, and you can use your online translation tool of choice if, like me, you’re not up on your German. With permission, I’ll share portions of what Mayert discussed in our email exchange.

The findings were interesting. On the one hand, Mayert found that “employees have no problem at all with companies taking a superficial look at their social media profiles to observe what is in any case only a mask in Goffman's sense.”

Erving Goffman, you may recall, was a mid-twentieth century sociologist, who, in The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life, developed a dramaturgical model of human identity and social interactions. The basic idea is that we can understand social interactions by analogy to stage performance. When we’re “on stage,” we’re involved in the work of “impression mana