Forget Calvinism. Become a Zwinglian.

Description

I used to think that Calvinism was simply a system of soteriology.

But I’ve come to see that there’s something more, a Calvinist vibe: to exaggerate human sinfulness in order to exaggerate the role of the grace of God.

Before Calvin’s time, Zwingli articulated a Reformed theology that was deeply humane, sympathetic to the foibles and weakness of sinful human nature.

If we take “the Zwingli option,” the fact that our nature is already predetermined in various ways does not make us the more evil and wicked and guilty. Rather, it provides a reason to sympathize with our condition, to treat others with greater mercy, not greater condemnation.

Welcome, reader. In this post, I’ll explain why it’s time to forget Calvinism and become a Zwinglian.

By the way, I’m Joel Carini, “The Natural Theologian.” I write essays on Substack to help Christians learn from secular sources.

And I make videos on YouTube about God for people whether you believe what I believe, something different, or nothing at all. (This post was originally a video. Please subscribe to my YouTube channel as well.)

The Calvinist Vibe

Calvinism.

I came to these set of views when I was a young man, as many do.

When I first arrived at Calvinism, it was out of a sense that my own conversion to Christ and the moral renovation that began to occur in my heart weren’t really down to me making a decision, i.e., finally deciding to get my life together, but that the initiative had come from God.

When you start from that point, you get the idea that we can’t just decide for Christ on our own, sin holds us back: total depravity and unconditional election, from which follow limited atonement, irresistible grace, and the perseverance of the saints. (TULIP!)

While I thought that Calvinism was simply this system of soteriology, since then, over the course of 15 years as a Calvinist and three years intensively studying at a premier Calvinist seminary, I’ve come to see that there’s something more. If you will, a Calvinist vibe.

This vibe is to exaggerate human sinfulness in order to then expound upon and exaggerate the role of the grace of God. By increasing the severity of our description of human sinfulness, we make theology and Reformed theology all that more important. (“Let us describe things as sin that grace may abound!”)

In the process, I fear we’ve begun to denigrate human nature. We say that human beings can’t know anything apart from scripture or apart from the Holy Spirit intervening in our minds. We say that nothing people do outside of Christ has any value apart from maybe God’s intervention as common grace. We say that everything we do, even as Christians, is wicked and evil and is ultimately filthy rags, even when the Holy Spirit is working in us.

All this we say, purporting to glorify the grace of God, forgetting that God is also the creator of our nature.

We should not exaggerate the effect of the fall upon that creation as if it obliterated the image of God in man.

For a while I’ve sought to argue that this isn’t real Calvinism. These are some extra add-ons, this exaggeration of sinfulness. And if we could get back to true Calvinism, we could avoid these problems. I’ve thought that the extra errors came from going the radical side of the Reformation, the Anabaptist tradition, which denigrated the world and focused on staying pure from it within the church.

But once an error is made a certain number of times, you have to question whether there isn’t something wrong towards the root. And then you start to wonder whether Reformed theology couldn’t have gone a different direction. Was there some fork in the road and we took the wrong route?

That is indeed possible. Martin Luther nailed his theses to the Wittenberg church door in 1517. And John Calvin, who we know as the first reformed pastor and theologian, did not experience his conversion until 1533. What was going on in the intervening years?

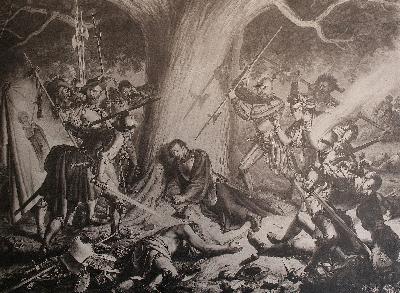

The ministry of Ulrich Zwingli. Zwingli’s entire career ended in 1531 with his death in a battle — before Calvin’s conversion even occurred.

Before Calvin’s time, Zwingli articulated a Reformed theology that was deeply humane, sympathetic to the foibles and weakness of sinful human nature, and appreciative of the work of God in creation and beyond the bounds of the Church.

The Zwingli Option is the one we never took.

In this post, I’m going to describe five points of Zwinglianism and articulate why I think this is the direction Reformed theology ought to go.

For further reading on Zwingli, I recommend Bruce Gordon’s biography of Zwingli, Zwingli: God’s Armed Prophet, which I am currently reading. Also, Zwingli’s On Providence and Other Essays, which includes his discourse on original sin. I recommend this interview of Dr. Gordon by Austin Suggs for an intro to Zwingli’s life.

1. Original Sin Is Not Sin, But Defect

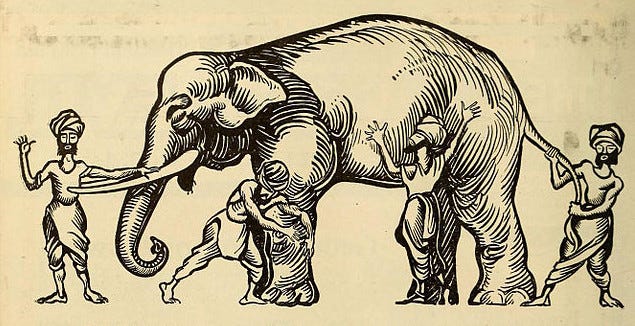

Zwingli held that original sin — our innate disposition away from God and towards sin — is not something for which we are to blame, but rather a defect in human nature that is a punishment of the fall.

In contrast to the later Reformed tradition, Zwingli did not think we were guilty on account of original sin. He did not think we were guilty on account of sinful desires and temptations, but only for sinful action.

This position came out of a whole debate about whether babies were damned to destruction, and Zwingli thought that that was a horrible position to hold. Before they have done any good or evil, simply because they were born with original sin as a result of Adam’s fall, infants were to be condemned to destruction. Zwingli held that, no, these children have done no wrong, even though as a reformed theologian he held that they were subject to original sin.

But original sin, Zwingli wrote, even though we call it “original sin,” is not a sin on our part, but a condition into which we are born where our motivations are not aligned with God’s purposes. And we can sympathize with human beings who are born this way, subject to this defect and to any particular form of sinful defect. (Contra Stephen G. Adubato: video.)

Zwingli himself put it this way:

Original sin is like a defect and a lasting one, as when stammering, blindness, or gout is hereditary in a family. On account of such a thing, no one is thought the worse or the more vicious, for things which come from nature cannot be put down as crimes or guilt.

This point of Zwinglianism became prominent as I left seminary. I’d already studied Calvinism, and I saw theologians trying to wrestle with the idea of same-sex attraction, that some Christians possess a homosexual orientation.

They struggled to deal with it theologically. They said, isn’t this concupiscence? Isn’t this original sin within them? Isn’t it something for which they are to blame, that they must repent of? And all of a sudden Reformed theologians, who I thought had never really discussed this matter, were completely aligned that 17th-century theology had already determined that same-sex attraction was sin.

But if we take the Zwingli option, we have quite a different result. The fact that our nature is already predetermined in various ways, different of us in different ways, does not make us the more evil and wicked and guilty. Rather, it provides a reason to sympathize with our condition, that we have to fight against our nature, that our nature is already determined against the will of God, and that in order to follow Jesus Christ, we must take on the yoke of fighting against that nature.

Original sin is like a congenital blindness (“Did this man sin or his parents that he was born blind?”) toward the good and toward the will of God with which we ought to sympathize and understand people’s struggles. (See “The Man Born Blind,” by Grant Hartley for this connection.)

As I’ve found, if we appreciate the doctrine of original sin in this way, it gives us reason to treat others with greater mercy and not greater condemnation.

Hey, if you enjoy conte