Podcast episode 35: Interview with Nick Thieberger on historical documentation and archiving

Description

In this interview, we talk to Nick Thieberger about the value of historical documentation for linguistic research, and how this documentation can be preserved and made accessible today and in the future in digital form.

<figure class="wp-block-audio"></figure>

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

References for Episode 35

Crane, Gregory, ed. 1987–. Project Perseus. Web resource: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/

Gardner, Helen, Rachel Hendery, Stephen Morey, Patrick McConvell et al. 2020. Howitt and Fison’s Archive. Web resource: https://howittandfison.org/

Lillehaugen, Brook Danielle, George Aaron Broadwell, Michel R. Oudijk, Laurie Allen, May Plumb, and Mike Zarafonetis. 2016. Ticha: a digital text explorer for Colonial Zapotec, first edition. Web resource: http://ticha.haverford.edu/

Takau, Toukolau. 2011. “Koaiseno”, in Natrauswen nig Efat, Stories from South Efate, ed. Nick Thieberger, pp. 88–90. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. Open access: http://hdl.handle.net/11343/28967

Takau, Toukolau. 2017. “Koaiseno”, in recording NT1-20170718. https://catalog.paradisec.org.au/collections/NT1/items/20170718

Thieberger, Nick. 2017. Digital Daisy Bates. Web resource: http://bates.org.au

Thieberger, Nick, Linda Barwick, Nick Enfield, Jakelin Troy, Myfany Turpin and Roman Marchant Matus. 2022–. Nyingarn: a platform for primary sources in Australian Indigenous languages. Web resource: https://nyingarn.net/

Pacific and Regional Archive for Digital Sources in Endangered Cultures (PARADISEC). https://www.paradisec.org.au/

Transcript by Luca Dinu

TT [singing]: Koaiseno koaiseno seno, nato wawa nato wawa meremo… [00:13 ]

JMc: That was the late Toukolau Takau from Erakor village, Vanuatu, singing Koaiseno, a song that’s part of the folktale of the same name. [00:24 ] The recording of the song is stored in the PARADISEC digital archive, which we’ll talk about later in this episode. [00:31 ] Links to the recording and the complete story are included in the bibliography for this episode. [00:38 ] I’m James McElvenny, and you’re listening to the History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences Podcast, online at hiphilangsci.net. [00:47 ] Today we’re joined by Nick Thieberger, who’s Associate Professor of Linguistics at the University of Melbourne. [00:55 ] Among his many interests, Nick works extensively with archival data, both contemporary and historical. [01:03 ] We’re going to talk to him about how historical data can inform present-day linguistic research, [01:09 ] and what we can do in our present to ensure that it becomes the most productive past of the future, if I can put it that way. [01:17 ] So Nick, you’ve been involved in a number of projects that make historical sources in Australian languages accessible to present-day communities and researchers. [01:27 ] The most significant of these are perhaps the Howitt and Fison Archive and the Digital Daisy Bates. [01:34 ] So can you tell us about these projects? What historical materials did you work with, [01:40 ] how did you make them accessible to people today, and what are the use of these materials today? [01:48 ]

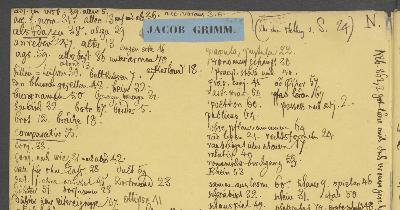

NT: Yeah, so these are a couple of major projects, and in some ways they were testing out a method for how to work with historical manuscripts. [02:01 ] I was only slightly involved with Howitt and Fison, but I ran the Digital Daisy Bates project, so maybe I’ll talk about that one. [02:09 ] Daisy Bates recorded on paper lots of information about Australian Indigenous languages in the very early 1900s. [02:18 ] So in 1904, she sent out a questionnaire, and that was filled out by a number of respondents. [02:23 ] And so there were in the order of 23,000 pages of questionnaire materials sitting in the National Library of Australia and two other libraries, [02:35 ] the State Library of Western Australia and South Australia. And so they were fairly inaccessible. [02:39 ] I’d worked with them, and I realised that they were very valuable, but they were really difficult to work with because they’re just all on paper. [02:48 ] So I thought it’d be interesting to try all of this methodology that we have with the Text Encoding Initiative and all these ways of dealing with texts and manuscripts. [02:58 ] So I worked with the National Library of Australia, and that took a bit of time because they’re a big institution and these things take time. [03:05 ] But it took about eight years, really, of getting the approvals from the National Library and also getting them to digitise these papers. [03:14 ] And they did that from microfilms, so not going back to the original papers, but… Because it was just much cheaper and easier to run the microfilms through and digitise them. [03:23 ] So then we had the images, and this was going back a while now, and OCR, optical character recognition, wasn’t very good for these typescripts. [03:33 ] So I sent them off to an agency to get them typed and then put them online. [03:39 ] And the idea, the principle behind this too, was that we should have an image of the original manuscript together with the text, [03:46 ] because, if you like, the warrant for the text is the original manuscript, and separating them, which is something that we’ve done a lot in the past, [03:55 ] we’ve gone in, found manuscripts, extracted what we think is the important information, reproduced it in some way, but then there’s no link back. [04:04 ] And so people can’t retrace your steps, [04:07 ] and if you’ve made some errors or just you’ve made some interpretations that they don’t agree with, there’s no real way for them to correct that. [04:15 ] So Digital Daisy Bates put the page images online and it put up the text, and you could then search the text, [04:24 ] and for every text page that you found, you retrieved the page image as well. [04:30 ] It’s been up online now for quite a while, and it’s had many, many users. [04:35 ] I think one of the exciting things about doing this sort of work is that once you prepare material in this way, you don’t know what uses people will make of it. [04:45 ] And one of the big target groups for this was Aboriginal people who wanted access to materials in their own languages, and that was satisfied. [04:55 ] But I was finding biologists who were finally able to search through 23,000 pages of Bates’ materials for plant and animal names. [05:06 ] Before, they were having to look through paper, and basically it defeated them, I think. [05:11 ] They were really not able to do it. [05:13 ]

JMc: And all this material is still up online and available for anyone to use. [05:18 ]

NT: Yeah, it is still up online and available for anyone to use. [05:21 ] And, you know, one of the issues with a lot of this is, what right do I have to put this online, and what changes digitisation makes, what changes it can make to the nature of the material. [05:36 ] So while it’s on paper, it’s got its own inherent restrictions. [05:40 ] You know, you can’t easily get access to it. [05:42 ] Once it’s online, it’s much more easily accessible. [05:45 ] So I was a bit worried with Daisy Bates. [05:47 ] This is mainly Western Australian material, and it represents dozens of languages and a huge geographic area. [05:55 ] There would be people who would feel perhaps aggrieved that they may feel some ownership of the language and not want it to be put online, [06:05 ] but I also recognised the value of putting it online. [06:10 ] So there was a risk. [06:11 ] And I think we have to take these risks. [06:13 ] I don’t think it’s very fruitful to say, “Oh, there’s a risk that somebody will be offended, so I won’t do this,” [06:20 ] because really, my experience with Daisy Bates is that everybody, all the Aboriginal people who’ve used it, have really valued being able to use it and finding materials. [06:29 ] And they can download this stuff and use it themselves as text. [06:32 ] So we have to be a bit less cautious. [06:35 ] I mean, obviously,