Podcast episode 43: Judy Kaplan on universals

Description

In this interview, we talk to Judy Kaplan about universals in American linguistics of the mid-20th century.

<figure class="wp-block-audio"></figure>

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | YouTube

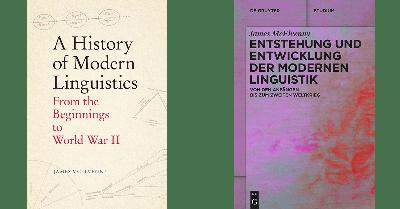

References for Episode 43

Emmon Bach & Robert T. Harms, Universals in Linguistic Theory (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968)

Noam Chomsky, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1965).

Jamie Cohen-Cole, The Open Mind: Cold War Politics and the Sciences of Human Nature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

Joseph Greenberg, “Some Universals of Grammar with Special Reference to the Order of Meaningful Elements,” in Idem (ed.), Universals of Language (Cambridge, MA: M.I.T. Press, 1963), 73-113.

______ “The Nature and Uses of Linguistic Typologies,” IJAL 23: 68-77.

Roman Jakobson, Kindersprache, Aphasie und allgemeine Lautgesetze. (Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksell, 1941).

Linguistic Society of America, Committee on Endangered Languages and their Preservation, “The Need for the Documentation of Linguistic Diversity,” June 1994. (https://old.linguisticsociety.org/sites/default/files/lsa-stmt-documentation-linguistic-diversity.pdf)

Janet Martin-Nielsen, “A Forgotten Social Science? Creating a Place for Linguistics in the Historical Dialogue,” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 47(2): 147-172.

Transcript by Luca Dinu

JMc: Hi, I’m James McElvenny, [00:09 ] and you’re listening to the History and Philosophy of the Language Sciences podcast, [00:13 ] online at hiphilangsci.net. [00:16 ] There you can find links and references to all the literature we discuss. [00:20 ] Today, we’re talking to Judy Kaplan, who’s a historian of the human sciences and a Curatorial Fellow at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia. [00:30 ] One of Judy’s current projects is to investigate the notion of universals in American linguistics of the mid-20th century. [00:39 ] Why is it that various competing schools of American linguists in this period converged [00:44 ] on universals as the target of their research, despite their fundamental differences in scientific outlook? [00:50 ] What did they mean by “universals”, and what role did universals serve in their respective theories? [00:57 ] So, Judy, can you sketch the scene for us? [01:01 ] What was happening in American linguistics in the mid-20th century? [01:04 ] Who were the leading figures, and what positions did they take? [01:09 ]

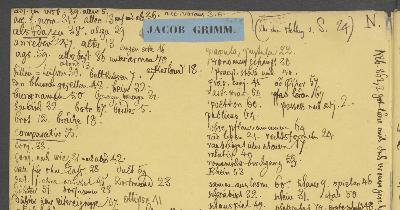

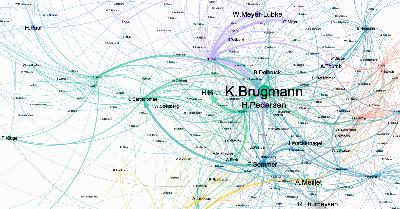

JK: Thanks so much. [01:10 ] Viewed from above, we can see that the mid-20th century was a time of remarkable growth and expansion in American linguistics, [01:18 ] so funding went up, the first university departments were established, and the ranks generally grew. [01:25 ] These markers corresponded to a handful of different programs or positions. [01:30 ] As far as those leading figures and positions, most people concentrate on two dominant approaches to the study of language at this time: structuralism and generative grammar. [01:42 ] I should say that both were internally heterogeneous. [01:46 ] On the structuralist side, there were students of Edward Sapir in the anthropological tradition and Leonard Bloomfield on the more strictly linguistic side. [01:54 ] Structuralists focused on speech, a sort of self-conscious departure from 19th-century philology, on form, [02:01 ] on abstractions — ultimately, as the name suggests, on structure. [02:06 ] In terms of evidence, they were heavily invested in the study of Native American languages. [02:12 ] By the post-war period, the so-called neo-Bloomfieldians or distributionalists were at centre stage. [02:19 ] So, figures here are people like Charles Hockett, Zellig Harris, Bernard Bloch, Martin Joos, and others. [02:26 ] To your question, their position was basically that linguists should be looking at how linguistic forms show up in different speech environments. [02:33 ] They insisted on the distinction of different levels of analysis — so, phonology, morphology, syntax, these were all different levels. [02:40 ] And these points of emphasis pretty much bracketed meaning and the mind, which is important. [02:47 ] Much of the work was really mathematical in terms of its look and feel. [02:51 ] Emerging in a sense from this tradition, but also deeply critical of it, was Noam Chomsky and the study of transformational grammar. [02:58 ] This program elaborated transformational rules, and that was a term that was adapted from Harris, so you can see that there’s this kind of emergence. [03:06 ] So, it elaborated these transformational rules to link fundamental deep structures of language to surface manifestations, allowing linguists to turn from empirical data toward the study of grammar and the mind. [03:19 ] The emphasis was on theory construction, evidence of linguistic competence, and the definition of rules. [03:25 ] Though this program subsequently splintered into groups dedicated primarily to syntax and semantics, it did come to define a new mainstream. [03:35 ]

JMc: So, how do universals fit into this picture? [03:39 ]

JK: In a very broad sense, I think universals trace back to the supposed liberation of linguistics from philology — the question being, was linguistics going to be about language or languages? [03:49 ] So, if the former, then one might reasonably be on the lookout, at the end of the day, for features or phenomena that are universal in scope. [03:59 ] Just circling back then to the general lay of the land, it’s interesting that historians of science — so I come out of history of science — that they have tended to write about this with different points of emphasis, as opposed to linguistic historiographers or historians of linguistics, first and foremost. [04:16 ] Historians of science have characterized the relationship between these two approaches (the structuralist and the generative) as the contrast between behaviourism and mentalism, which was given all sorts of ideological overtones in the post-war period. [04:31 ] Linguists writing about their own history have wrestled with whether or not the remarkably swift emergence of transformational grammar constituted a scientific revolution in the Kuhnian sense. [04:42 ] It was unquestionably a remarkable turn, so participant accounts, institutional changes, interdisciplinary engagements, and citation patterns all make that really clear, [04:52 ] but there were also many linguists who were already trained and working in the structuralist tradition who felt that transformational grammar was not really for them. [05:01 ] And I might locate Joseph Greenberg somewhere in there, right? [05:05 ] So he was coming out of anthropology, first and foremost, he received his PhD in anthropology, and became really well-known by the 1950s for working on the genetic classification of African languages. [05:19 ] He was quite well regarded for that work. [05:22 ] He first turned to the study of African languages because he had been interested in Arabic and Semitic and had been approaching these from an anthropological standpoint, [05:31 ] and in 1957, he started to write about typology, and typology in connection to universals. [05:38 ] So Greenberg is taking a typological approach to the study of language universals, and he is leaning pretty heavily on the work of Roman Jakobson, who had introduced them in connection to the acquisition of child language. [05:52 ] One of the things that he says here is that it’s really important to consider implicational universals, so of the form “if X, then Y,” [05:59 ] and he sets out on a kind of data-gathering mission with this in mind. [06:04 ] And, you know, when he tees up the program — this was launched in a 1961 conference at Dobbs Ferry — [06:11 ] when he tees up the program, he says, you know, We have accumulated so much data at this point in time that the time is ripe to turn to the study of language universals. [06:22 ] Coming back to the questio