Podcast episode 37: Interview with Michael Lynch on conversation analysis and ethnomethodology

Description

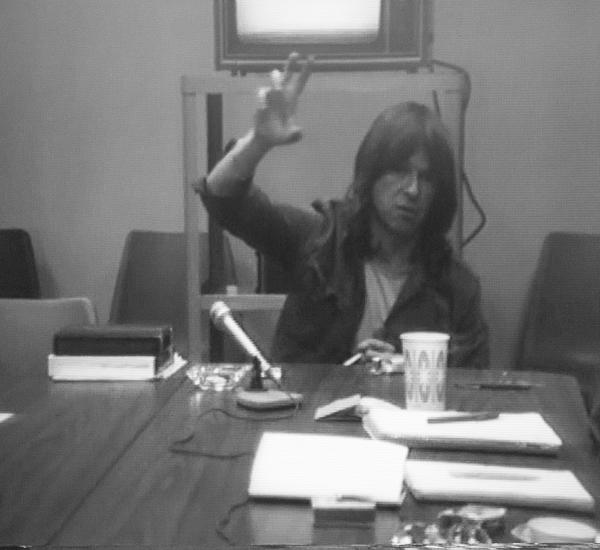

In this interview, we talk to Michael Lynch about the history of conversation analysis and its connections to ethnomethodology.

<figure class="wp-block-image size-large">

</figure>

</figure><figure class="wp-block-audio"></figure>

Download | Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

References for Episode 37

Button, Graham, Michael Lynch and Wes Sharrock (2022) Ethnomethodology, Conversation Analysis and Constructive Analysis: On Formal Structures of Practical Action. London and New York: Routledge.

Fitzgerald, Richard (2024) “Drafting A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation,” Human Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-023-09700-7

Garfinkel, Harold (2022) Studies of Work in the Sciences, M. Lynch, ed. London & New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003172611 (open access)

Lynch, Michael (1993) Scientific Practice and Ordinary Action. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lynch, Michael and Oskar Lindwall, eds. (2024) Instructed and Instructive Actions: The Situated Production, Reproduction, and Subversion of Social Order. London and New York: Routledge.

Lynch, Michael and Douglas Macbeth (2016) “Introduction: The epistemics of Epistemics,” Discourse Studies 18(5): 493–499. See also the articles in the special issue.

Sacks, Harvey (1992) Lectures on Conversation, Vols. 1 & 2, Gail Jefferson, ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, Harvey (1970) Aspects of Sequential Organization in Conversation. Unpublished manuscript, U.C. Irvine.

Sacks, Harvey, Emmanuel A. Schegloff and Gail Jefferson (1974) “A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation”, Language 50(4), Part 1: 696–735. Available online

Transcript by Luca Dinu

JMc: Hi, I’m James McElvenny, and you’re listening to the History and Philosophy of the Language [00:14 ] Sciences podcast, online at hiphilangsci.net. There you can find links and references to [00:20 ] all the literature we discuss. Today we’re joined by Michael Lynch, who’s Professor Emeritus [00:26 ] of Science and Technology Studies at Cornell University. He’s going to talk to us about [00:32 ] conversation analysis and its links to ethnomethodology.

It’s probably fair to say that conversation [00:40 ] analysis, or CA, is a well-established subfield of linguistics today, which is concerned with [00:47 ] studying how interaction is achieved between speakers in an oral exchange. On a technical [00:54 ] level, conversation analysts typically proceed by making an audio or video recording of an [00:59 ] interaction and then transcribing it in a heavily marked up notation that conveys elements [01:06 ] of intonation, overlapping speech, gaze, and so on. Using these transcripts as empirical [01:12 ] evidence, the analysts then put forward theories about how the back-and-forth of conversation [01:18 ] is structured.

The seminal publication introducing conversation analysis was a 1974 article in [01:26 ] Language with the title, “A Simplest Systematics for the Analysis of Turn-Taking for Conversation”, [01:33 ] co-authored by Harvey Sacks, Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson. These three are widely considered [01:41 ] the founding figures of CA. But crucially, Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson had not been trained in [01:48 ] traditional linguistics programs. They were sociologists by academic upbringing. Moreover, [01:54 ] they were adherents of ethnomethodology, an approach to sociology pioneered by Harold Garfinkel. [02:02 ]

So the question arises as to how conversation analysis fits into linguistics and this broader [02:09 ] disciplinary constellation. Mike, can you illuminate this question a bit for us? [02:14 ] Where did conversation analysis come from, and how is it placed today? [02:19 ]

ML: OK, well, thank you, James, for the opportunity to speak to your podcast. To start, I’d like to [02:26 ] add that what you said about Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson also applies to me. I’m not trained as a [02:34 ] linguist, traditional or otherwise. My background is in sociology, but also like them, [02:39 ] I spent a lot of my career, particularly the last 25 years at Cornell, in interdisciplinary programs [02:46 ] of which sociology was a part. But my take on sociology through the field of ethnomethodology [02:53 ] is not normal sociology, as many people would tell you. I don’t want to go into that right now.

But [02:59 ] you asked about the background of Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson and where CA came from. I know less [03:06 ] about Schegloff’s and Jefferson’s background a little bit, but I know more about Sacks, [03:12 ] partly because I’ve been spending the last year and a half reading and rereading the two-volume [03:19 ] set of his lectures. A little bit about Schegloff. He wrote an MA thesis on the history of literary [03:26 ] criticism before pursuing a PhD in sociology at Berkeley at the same time that Sacks did. [03:32 ] Jefferson had an education and practical experience in dance choreography before she attended Sacks’s [03:40 ] lectures and switched into a PhD program with him at UC Irvine, and her father was a famous [03:48 ] radio psychiatrist.

Sacks had a law degree from Yale in 1958 and after that decided, [03:55 ] to the disappointment of his parents, not to pursue a law career. He was in the MIT, Cambridge, Harvard [04:05 ] area when he decided he wanted to go back to sociology and political science. He had studied [04:13 ] sociology as an undergraduate and he met Garfinkel and I believe also Goffman, who were on sabbatical [04:20 ] taking seminars from Talcott Parsons, a famous sociologist and Garfinkel’s mentor. And from there [04:29 ] he really hit it off with Garfinkel. Garfinkel encouraged him to go to the West Coast [04:34 ] and he pursued his PhD in sociology at Berkeley, where he did, for a time at least, work with [04:40 ] Goffman, although Goffman did not sign his PhD. And he stayed in touch with Garfinkel, was part [04:47 ] of groups that met, kind of forming the basis of ethnomethodology, which, to put a short gloss on [04:55 ] it, is the study of everyday actions as they are performed, at least preferentially in the case [05:03 ] of CA, using recordings of interaction naturally occurring (so-called) as a material for study. [05:12 ]

Sacks also was very widely read. I really recommend reading his lectures or at least some of them [05:19 ] because there – you can still get them online. They’re out of print, I believe. It makes clear [05:26 ] that he’s drawing from the history of oral languages, the cultures of ancient Greece and [05:33 ] Rome, the studies of Judeo and biblical culture and language. He also was apprised, to what depth [05:44 ] I don’t know, of ordinary language philosophy, Austin, Searle to some extent, but mainly Austin [05:51 ] and Wittgenstein as well. He didn’t mention it much in his writings or in his lectures, [05:58 ] but his sensibilities were definitely shaped by that background. And he also brings in themes [06:04 ] from law, which is not really obvious, but when you read the lectures and some of his unpublished [06:09 ] writings, you find that he has kind of a legal orientation to the organization, the rules, [06:17 ] the norms, procedures of ordinary conversation. There’s a bit of a legal background into what [06:23 ] he’s saying.

Now, you mentioned the 1974 paper on simplest systematics and turn-taking by [06:30 ] Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson. It’s often taken to be the beginning of conversation, [06:34 ] but his lectures, starting when he was a graduate student and living in Los Angeles and teaching [06:40 ] at UCLA, they start in 1964, so 10 years before that, and even the earlier lectures exhibit [06:49 ] themes about language,