Decolonising Porirua

Description

EPISODE SUMMARY: On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism, we travel to Porirua, Wellington to learn about Imagining Decolonised Cities, a project designed to stimulate discussion around what our cities could look, feel, sound, taste and smell like if they were decolonised.

GUESTS: Rebecca Kiddle, Fiona Ting, Jessica Hulme

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Jade Kake v/o: If we walk around our cities in Aotearoa, they feel like colonial spaces. This is changing, slowly, but on the whole they don’t feel very Māori. In general, they don’t reflect the hau kāinga or local people of that place.

Our cities in New Zealand have, for the most part, taken shape according to Eurocentric values. Pre- and early- European contact, Māori had kāinga and pā where all the major cities were founded, but were dispossessed of their land in order for these cities to be built.

Māori concerns have historically been understood as rural despite the fact that most Māori live in cities, and urban spaces are turangawaewae for a number of iwi and hapū.

So, what is a decolonised city anyway?

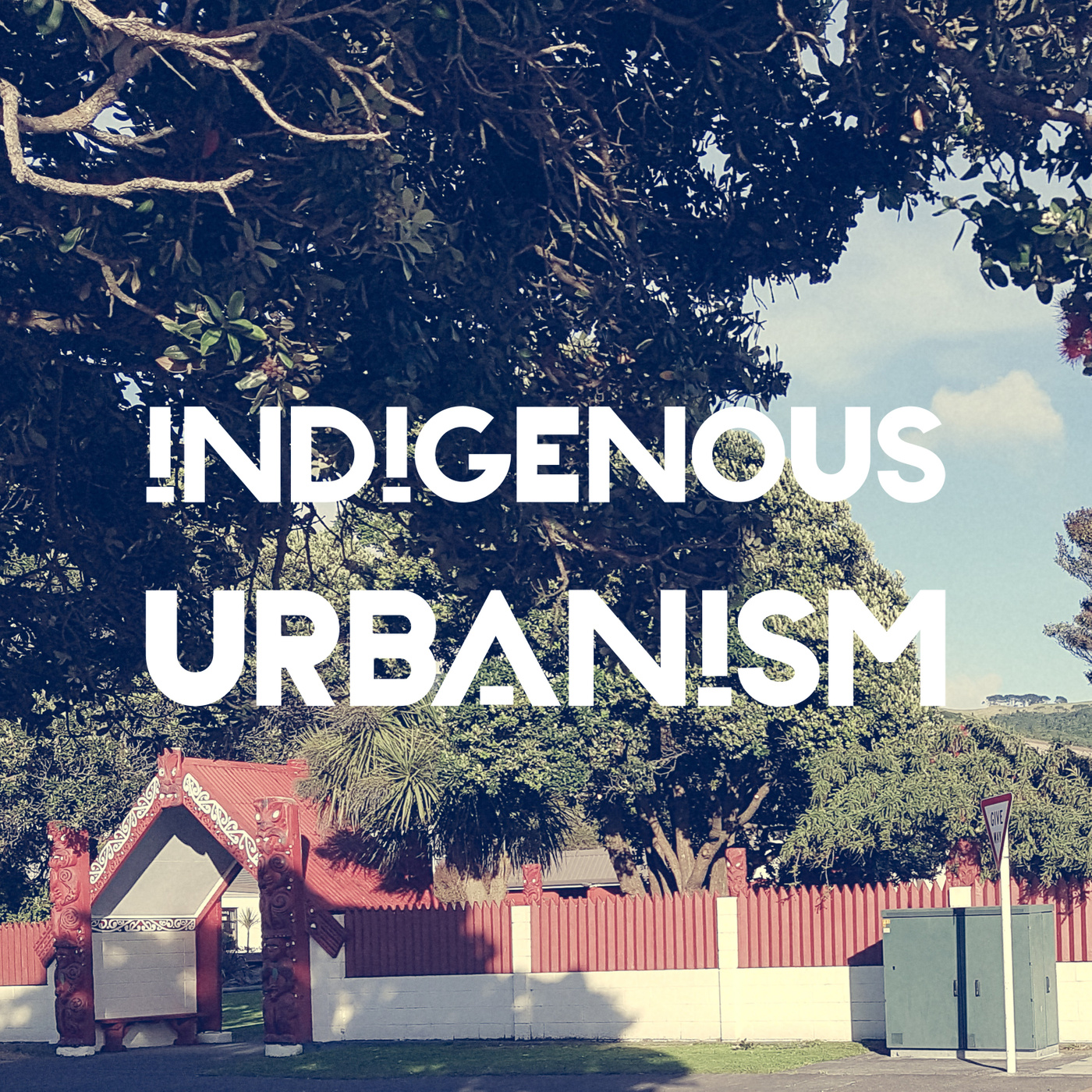

Rebecca Kiddle: We wanted to explore this idea of decolonisation, and that really started from not really understanding what that might mean, in relation, particularly to the build environment. New Zealand often understands itself to be a rural place. And maybe you've heard people talk about this before, but we're one of the most urbanised countries in the world, and yet we still understand ourselves to be, you know, people with sheep basically. The reasons for exploring that are, that it becomes pretty problematic if we conceptualise ourselves to be rural, in relation to Māori identity. So what I think happens, is people understand Māori-ness to be a rural thing. It's not an urban thing, it's not something that’s relevant to the City, and that’s problematic in two ways. First of all it kind of dismisses the mana of the iwi and hapū, for whom these places are theirs. So, Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Whātua in Auckland, and so on. It means that their identities aren't represented well in the built environment. I think the second is really about a sort of general kind of erasure of indigeneity in the built environment.

JK v/o: Tēnā koutou katoa

Nau mai haere mai ki te Indigenous Urbanism, Aotearoa Edition, Episode 18.

I’m your host Jade Kake and this is Indigenous Urbanism, stories about the spaces we inhabit, and the community drivers and practitioners who are shaping those environments and decolonising through design.

On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism we travel to Porirua to learn about Imagining Decolonised Cities, a project designed to stimulate discussion around what our cities could look, feel, sound, taste and smell like if they were decolonised.

The project did this through eliciting utopian ideas for a decolonised city through a public urban design competition, and a public symposium where speakers were invited to respond to the provocation ‘What is a decolonised city?’

We spoke with Dr. Rebecca Kiddle, nō Ngāti Porou raua ko Ngāpuhi, a senior lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington, and leader of the Imagining Decolonised Cities project.

RK: I te taha tōku kuia nō Ngāpuhi. I te taha tōku koroua, ko Hikurangi te maunga, ko Waiapu te awa, ko Ngāti Porou te iwi. I tipu ake au i Heretaunga, ko Becky Kiddle tōku ingoa. So I'm Ngāti Porou and Ngāpuhi, but I grew up in Kahungunu territory, and yeah, my name's Becky Kiddle and I'm a senior lecturer in environmental studies at Victoria University.

JK: Could you talk us through the project, and how it came about?

RK: That project came about cause I had spent a few years overseas. So I was overseas for about ten years, and I came back and sort of felt a little bit like our built environments hadn't moved on all that much, since I had left. There was obviously some real gains in some areas of the country, particularly around uptake of the Te Aranga principles in Auckland. But for the most part Māori were seen to be excluded from decision making processes around, just the form and function of our cities. In parallel with that, there was a real sense of pain, I guess, amongst Māori communities, around what cities were and meant to them. And that pain is for obvious reasons, all the government policies post-World War 2 that led Māori into the cities, and led to the demise of things like culture and language, and has caused a whole lot of pain amongst many Māori communities. Those are those coming from other rohe to be in the cities, but there's also pain amongst iwi for whom the city has always been their papakāinga or their tūrangawaewae or whatever. So, a sort of double-edged pain going on around cities and Māori. But I think the problem of conceptualising cities as all being about painful reminders of terrible government policy, is that we can miss out on the opportunities of cities, which I think there are many. And many of us younger Māori are quite keen to live in cities, because there's lots of opportunities to be who you want to be, and live in ways that you want to live. But there obviously could be more in terms of cities supporting Māori tīkanga, and just ways of being I guess. So, talking to some colleagues around the place here at Vic, we decided that we would really like to explore this idea of decolonisation. And it's kind of a lofty term decolonisation, it's used often in very highfalutin ways, and I was like, well what does that mean, exactly? What does it really, really mean. And, I think sometimes it's quite hard to make tangible the notion of decolonisation. So, the whole project was really about us trying to work out what decolonisation means for cities, and doing that in what we hoped was quite a democratic way actually. By opening up this competition to New Zealanders - all New Zealanders, not just Māori - and the reason it wasn't just for Māori is because we were very firmly of the opinion that decolonisation - whatever that might mean - is the work of everyone, not just Māori. Māori are so overcapitalised - is that the right word? They're drawn to be involved in a whole heap of things, and capacity is pretty low in terms of ability to be able to influence a whole host of things. So, decolonisation's got to be a shared effort, if we're actually ever going to achieve it. So, that was the impetus really, was about getting some tangible ideas about what it might mean for the built environment.

JK: Could you tell us about the competition?

RK: So the competition was funded by UNESCO, well the New Zealand arm of UNESCO, I think it's called the National Commission for UNESCO. And as I said, we opened it up to anyone, but we were particularly interested in three categories - so, under 18 year olds, we wanted a youth perspective, and the reason we wanted a youth perspective is because, our thinking was, that often young people are less muddied, I guess, by the impact of colonisation, and so we were hoping that they would have some really great ideas that perhaps are not rooted in a real strongly held sense of the impact of colonisation, which I think many of us older generation might have. And then we wanted to open it up to the general public, so we were really clear that we wanted anyone to be able to be involved in the competition, because those who live in cities are experts in living in cities, so therefore, why wouldn't they have good ideas in thinking about decolonisation for cities. And then finally, we were keen to involve professionals as well, because it's their bread and butter, and we wanted to see if they also had some interesting ideas for the city. With the young people, we were quite clear that we wanted to make sure that they felt able to participate. So we were concerned that if we just threw it open, young people might not necessarily take part. So we worked with secondary school aged children at Aotea and Mana colleges in Porirua, and we did a couple of two to three day wānanga with students to teach them and give them some urban design skills, and some communication skills that they might use to enter the competition. And a lot of them did enter. Not everyone entered, but many of them did enter, but in the meantime they got to experience the architecture school at Vic, and see what it might be like to come to university, and just give them some opportunities to understand what university life might be so they might be interested in coming.

JK v/o: The public urban design competition encouraged people to think about how we might ‘decolonise’ cities in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Two sites, at two different scales were offered on which to consider the question ‘What is a decolonised city?’ At the larger scale is the Onepoto arm of the Te Awarua o Porirua and shoreline.

RK: Partly we chose that because with a new roading system, transmission gully, the Eastern side of that harbour is going to change dramatically over the next few years, and the local Council were keen to get ideas about how they might redevelop the harbour. The harbour also was a key site for Ngāti Toa Rangatira, the local iwi. It was their food basket, and it was also the place where they went to heal over the years, and often due to government policy - like the Public Works Act - the harbour had been systematically polluted, and now is somewhere that they can no longer collect kai moana, or go to bathe.

JK v/o: At the smaller scale is a papakāinga site owned by the Parai whānau. One of the impacts of colonisation was the loss of what is now urban land from iwi and hapū ownership. In Porirua, Ngāti Toa Rangatira lost many acres of land, often via the Public Works Act.

RK: We had a papakāinga site, which was based on some land that a local whānau, the Parai whānau, had actually bought back from the government, despite it being taken from them. Under