In Conversation with Elisapeta Heta

Description

EPISODE SUMMARY: On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism, we speak with Elisapeta Heta nō Ngāti Wai, an architectural graduate working at Jasmax. Elisapeta is also an artist and academic, and has held various significant advocacy roles.

GUESTS: Elisapeta Heta

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Jade Kake: Tēnā koutou katoa

Nau mai haere mai ki te Indigenous Urbanism, Aotearoa Edition, Episode 7.

I’m your host Jade Kake and this is Indigenous Urbanism, stories about the spaces we inhabit, and the community drivers and practitioners who are shaping those environments and decolonising through design.

On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism, we speak with Elisapeta Heta nō Ngāti Wai, an architectural graduate working at Jasmax. Elisapeta is also an artist and academic, and has held significant advocacy roles, including her previous role as Co-Chair of Architecture Women, and current role as the Ngā Aho representative to the New Zealand Institute of Architects Board.

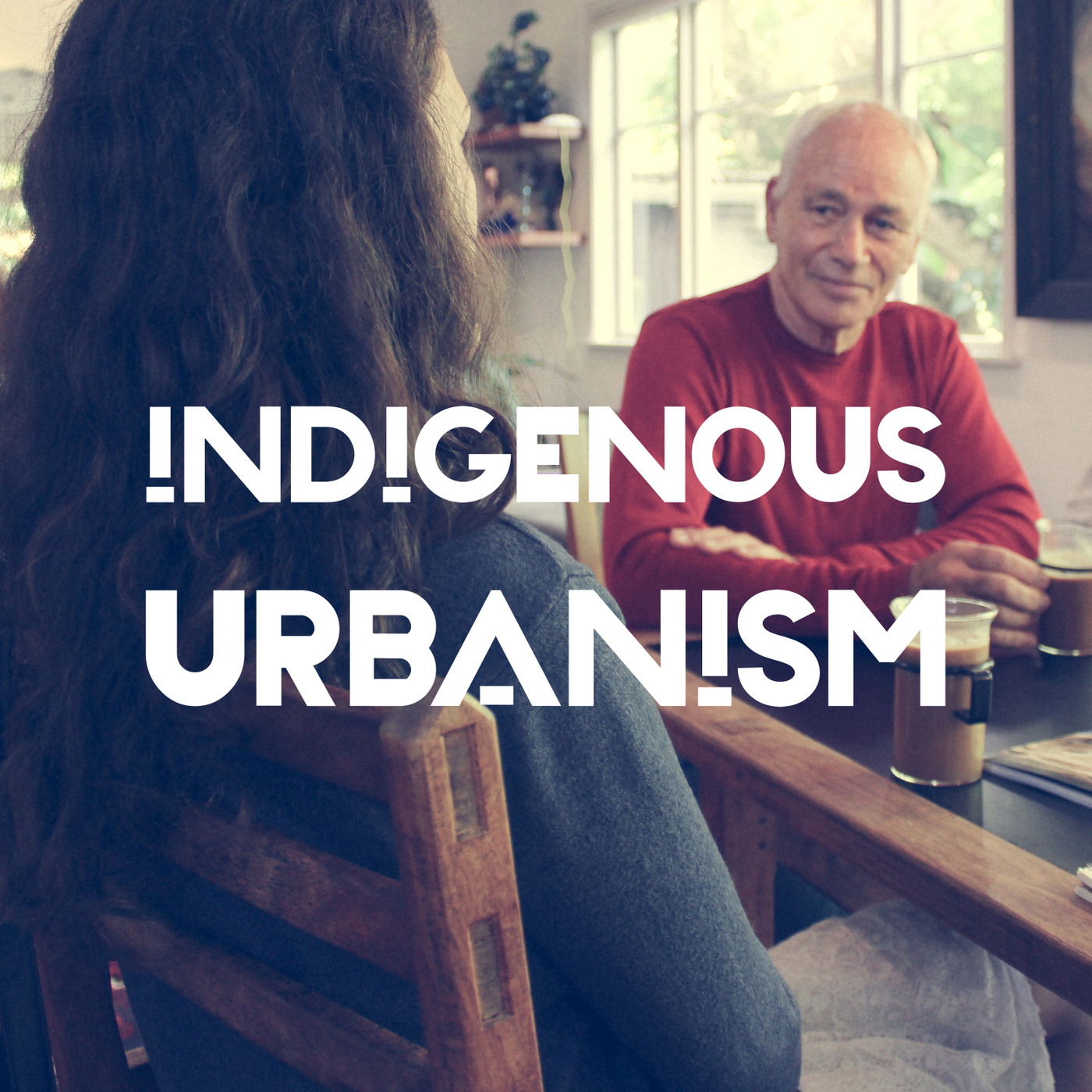

We caught up with Elisapeta at the Jasmax offices in Parnell.

JK: Ko wai koe? Nō hea koe? Where are you from, and who are you?

Elisapeta Heta: I am from many places actually. On my father's side I'm from up north, and a little bit south of here, so nō Ngāti Wai ahau, me Waikato-Tainui, and on my mother's side I am Samoan, Tokelauan, and English. So she's first generation New Zealander, whatever that means. Her mother was born in Apia, and her father was born in Portsmouth in England. So, from everywhere. Ko Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta ahau. I'm an architectural graduate at Jasmax, but I'm also part of a roopu here called Waka Maia. We are three architectural graduates, who run a lot of the - for want of better words - Māori navigation type stuff for projects. So we have boldly given ourselves the title of Kaihautū Whaihanga, so Māori design leaders within the practice.

JK: And so you find yourself in a really large firm, being one of a few Māori practitioners. So could you talk a little bit, just about that experience.

EH: Yeah, for me, for starters, it's quite funny as a graduate I think you sort of assuming you are going out into the world begging somebody to take you on as some kind of strange liability to them, or something. But I was very deliberate about choosing to want to come and work with Jasmax. And that was partly because Jasmax had a known reputation for working on community projects that involved Māori that I was really intrigued by. A lot of that was led and run by Ivan Mercep, who's since passed away. But he had quite the legacy, effectively, with Māori communities, with Māori projects. Even though he wasn't Māori himself, and had mentored Brendan Himona and sort of a little bit at the end there as well, Rameka Tu'inukuafe, who are both my colleagues in Waka Maia. Jasmax I think, sort of had a cultural capacity, shall we say. It had an understanding. It had a bit of - when I sort of found out the history of why Jasmad began, little bit of a radical sort of beginnings, and wanting to make the city a better place. And I suppose that's considered radical sometimes.

JK: Shockingly

EH: Shockingly, yeah. Protesting against motorways being built in ridiculous places, and all sorts of things like that. So, I think Jasmax just had, there was an inbuilt sort of sense for me, from the outside looking in, that it was something I could get in on. It's hard, I think, to build cultural capacity from scratch. Knowing that there were Māori colleagues already here that were trying to make things happen, that was sort of a nice transition, I suppose. It had some momentum, it had some legs. I came on at a time that Haley Hooper, another Māori wahine, had also joined Jasmax only six months prior to me starting here, so there ended up being four of us, which was a little bit of a bubble. And we, I think in sort of a momentum, kind of riding the wave of a whole lot of things happening outside of the office. So, the first time Māori had ever met officially with the NZIA had happened at the same time, and there were talks about the kawenata which eventually comes into being later on, I suppose, in the chronology of my life. So, being here, or coming here to Jasmax was kind of wanting to push myself where I thought was really important, with the kind of powerhouse that this already had, I suppose. Nothing's perfect, everybody, every group, every collective, every office, has things they can do better. I think that's what's been pretty amazing, personally from my point of view, is the willingness of this office to actually let us roam a little bit far, and then come back, and sort of genuinely start to initiate and embed a lot of the things that we thought were important from a te ao Māori point of view into business as usual at this practice. Which is pretty amazing, steering a ship of - you know last year it was over 300 people. So, you'd think change like that would take a long time, but it's been surprisingly flexible and adaptable.

JK: I liked what you said a bit earlier when you mentioned Ivan and the kind of relationships that he had with Māori communities, and they were very deep enduring relationships. And what I was really encouraged by is when you also talked about how he was bringing young Māori practitioners through in this process. Cause that's something I see a lot is that sometimes quite experienced Pākehā architects feel that they should occupy that space as a matter of right. And I kind of want to, I often want to challenge them on that, saying well, you don't occupy that space as a matter of right, and what are you doing to bring Māori practitioners into this space.

EH: Yeah well that's, we're seeing now, that now really bubble up as a conversation around cultural appropriation, right? Is the question of, what right do Pākehā have to occupy our spaces, our knowledge, our things that represent us. And for me, I always start with questions. What is it that they are giving back? How is it that they are supporting Māori, Māori communities? The knowledge where that has come from. What permissions have they sought out? Where does the mana lie? And I don't like to talk about mana often, because I find it's used as a means of currency, where it should not. But, I do genuinely mean, where - who is being uplifted, truly? Who is being empowered by what you are doing? That question actually applies to anybody. Pākehā, Māori, tauiwi alike. I think there's a lot to be said for Pākehā who have occupied and do occupy those spaces, and do it in such a way that they are breaking down barriers, and enabling those other people to step into those spaces. And I think of a lot of people off the top of my head who have been huge, hugely instrumental for me, I suppose, breaking through a barrier, demonstrating that it was possible, and then kind of pushing me through it. So I guess what I mean by that is, somebody like Ivan would be a really great example. You know, the kind of semi-invisible Maurits Kelderman at designTRIBE is another really good example of that. And he will never, he will never talk about himself in such a way that he is occupying that knowledge for himself. He is very much present for the kaupapa, and he will give you whatever knowledge he has. And, I have always found that very humbling, and quite inspiring. And I'm actually getting teary about it. And if he ever listens to this he'll laugh at me. But that's okay, and it's people like that who are really, really important. I saw a huge discussion about cultural appropriation breakdown on facebook. It was fascinating actually. On Tracey Tawhiao's facebook page. Yeah, but it was something like 600 comments deep. And there was this one comment from Aroha Gossage about her dad's mahi, Peter Gossage. All of the beautiful drawings that he did that brought us as children, like the whole country, you know the Maui stories, and he was a Pākehā man. And, I thought about that actually, her sort of challenge to that space of cultural appropriation. And she said, my dad has spoken, he did this, and everybody was kind of jumping in and going, oh my god yeah that wasn't cultural appropriation, and you know, we're really appreciative. And we are really appreciative, and I think in those times as well, that was Pākehā stepping into spaces that the mainstream probably weren't super stoked about. But it's breaking down barriers and enabling other things to happen. Whether or not that was exactly what they were thinking about at the time, I don't know, I can't speak to that. But, you know, I guess all I'm saying is, for me it's those critical questions around where the kaupapa sits, what your true intentions are - the road to hell is paved with good intentions - what those good intentions actually form, in terms of intangible outcomes and actions, and then just constantly being rigorous and critical about how you check yourself in that. That would be what I would ask of anybody operating in that space, but definitely of I think our Pākehā practitioners who sometimes mean well but maybe don't hit the mark, I suppose. And I still don't think about that in a, kind of like, I'm not giving anybody a lecture, or telling anyone off about it. I just think we all have the opportunity to grow. So I would hope this is people's opportunity to grow.

JK: Yeah and I think what you've described is actually just, like, the conditions for a really solid Treaty-based relationship.

EH: Exactly!

JK: Based on respect.

EH: Please!

EH: I really - gosh, if I had one sort of wish, it would be that people stopped seeing the Treaty as a negative, as associated with negative connotations. And I feel like what I mean by that, is that it was, it should have been and it was - to my mind - predicated on the idea that we had two peoples coming together. And working together. And negotiating what that meant. That's why it