In Conversation with Haley Hooper

Description

EPISODE SUMMARY: On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism, we speak with Haley Hooper nō Ngāti Hau, an urban designer living in Tāmaki Makaurau, who explains just what an urban designer is, and how we navigate our role as mataawaka practitioners.

GUESTS: Haley Hooper

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Jade Kake: Tēnā koutou katoa

Nau mai haere mai ki te Indigenous Urbanism, Aotearoa Edition, Episode 10.

I’m your host Jade Kake and this is Indigenous Urbanism, stories about the spaces we inhabit, and the community drivers and practitioners who are shaping those environments and decolonising through design.

On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism, we speak with Haley Hooper nō Ngāti Hau, an urban designer living in Tāmaki Makaurau, who explains just what an urban designer is, and how we navigate our role as mataawaka practitioners.

Kia ora Haley. Thanks for meeting me, and thanks for being on the podcast. The first thing I'd like to ask is, ko wai koe? Nō hea koe? Who are you and where are you from?

Haley Hooper: Kia ora Jade, thank you for having me today. It's a pleasure to be here and to be able to speak with you. Ko Huruiki to maunga, ko Whakapara te awa, Ngāpuhi te iwi, ko Ngāti Hau to hapū, ko Whakapara te marae, ko Ray raua ko Sheree ōku mātua, ko Haley tōku ingoa. Nō Whangārei ahau, engari nō Tāmaki Makaurau ahau ināianei. My name is Haley Hooper from up north, I'm from Whangārei originally. My mum's from Whangārei, and my dad's from Kaitaia. I moved to Auckland when I was 14 and lived in Takapuna and then followed on, went to university in Auckland, and here I still am in Tāmaki today.

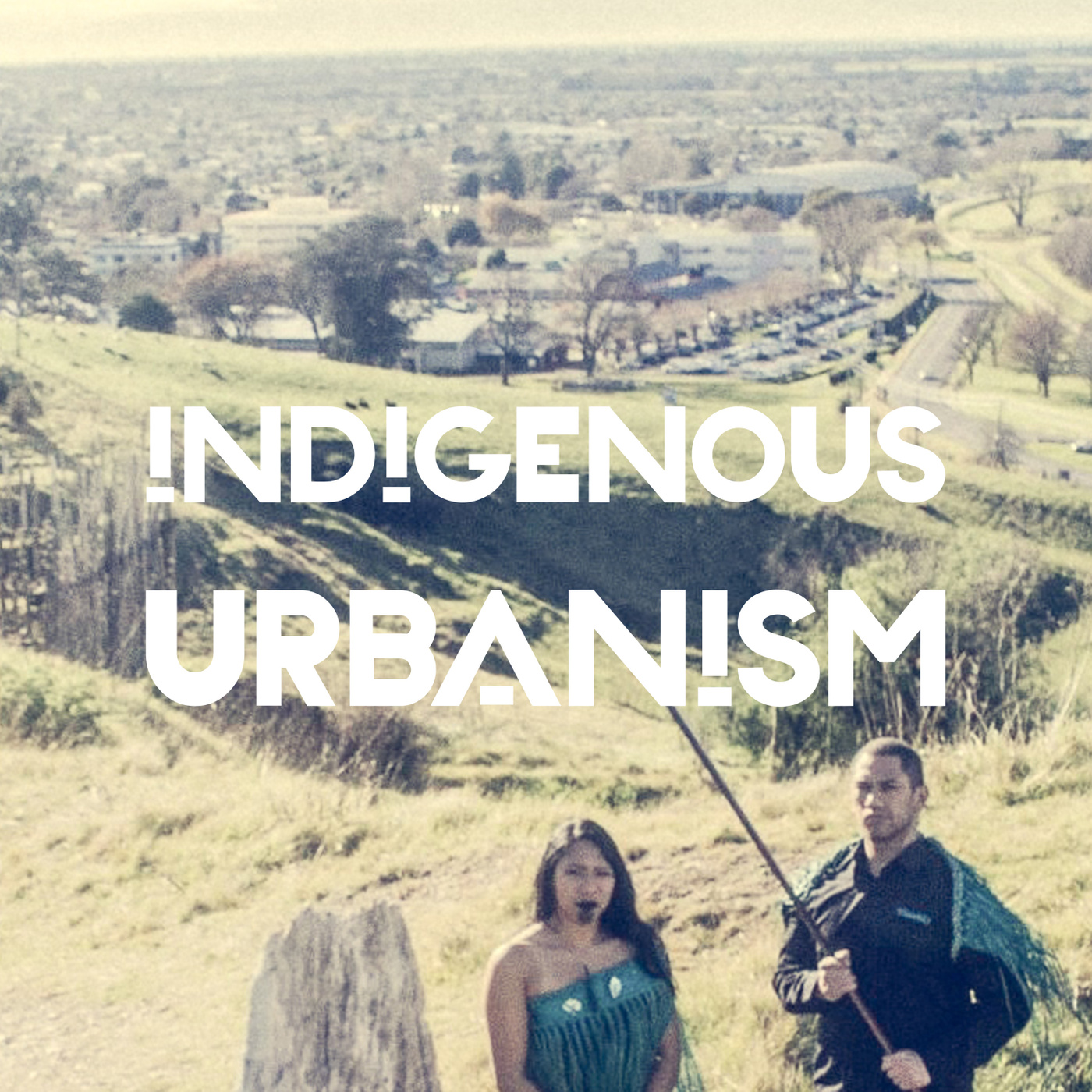

JK: We've met here at the top of Maungawhau Mt Eden in Tāmaki. I just wanted to ask you, why did you chose this place?

HH: So I guess for me, when you asked me to be interviewed I was trying to think of where we would be a place that does the kōrero justice, and a place where I really like to be. I think I always enjoy to be in outdoor environments, and being on the top of a maunga looking out across Tāmaki seemed like a pretty inspirational place and I was hoping that my thoughts might flow a little bit better up here.

JK: Kia ora to that. Now Haley you're an urban designer, but you're trained in and have started out your career in architecture. Which makes sense, because traditionally architects, as well as planners and landscape architects, took on that role of urban design, before it emerged as a distinct discipline. So, for those who don't know what urban design is, and what an urban designer does, could you explain that and how that has become its own thing?

HH: So I guess urban design is a fairly recent profession to have emerged. I would say kind of from around the 1950s, but much more predominantly in the last 20 to 30 years. Jane Jacobs was probably one of the founders of the profession in a sense I think. And yeah, it is a shift from architecture, landscape and planning. So, urban design is kind of like the crossroads of those three things coming together. People often speak about it being the design of the spaces in between, so the space in between buildings, or the stuff that knits cities together. So if you think about traditional European cities, it's much more evident what the urban design part is, because the space is so much stronger, the spatial dominance of what's actually in between the building. And you really feel and recognise what those spaces are, and the space as a thing and the buildings are a frame. Whereas I think sometimes in New Zealand you often find that the buildings are the object, and the space in between is secondary, and it's something you can't even almost read. So it lacks a form, and it kind of leaks everywhere. So, going back to the original question, urban design I think is most commonly known as the design of cities, and it's integration of the public realm, infrastructure, social and transport and servicing infrastructures. The negotiation of politics and planning - as joyous as that sometimes is or isn't - and development controls, and it's generally looking at design from that broader scale. Involving a number of buildings or spaces as opposed to one thing, but the collection of parts. And it can also be things like looking at economics, feasibility and evaluations, identifying opportunities for growth in the city or growth management, and looking at targeted areas where future urban development might happen. Plus it's definitely about culture, and it's absolutely about heritage, resilience, and things like accessibility as well. So I think it's a very difficult profession to define succinctly.

JK: Because it sounds like it's everything

HH: It's a little bit of everything, yeah, and that's probably why I like it.

JK: And so what did lead you to move on from purely architectural work, to more urban design mahi?

HH: So I think originally when I was studying at university I was always interested in things from an urban scale, and I kind of followed lecturers like John Hewitt, who were urban designers, just naturally, because I think of the social motivation, and the fact that you are doing things that change the common good or interested in the broader picture or the vision, strategy, for the design, as opposed to the architectural side, which can sometimes be about the object - it not always is, but. So, I guess, started at university, and then I went off and worked in a number of different areas of architecture, which was interesting from a design point of view, but I kept struggling with the fact that I wasn't able to contribute to things that are concerning, for me, really concerning the city, and community, and the bigger, broader scale ideas.

JK: So architecture felt quite limited and it perhaps didn't go far enough to achieve some of these broader social aims that we might hope that our work might encompass?

HH: Yes, and I think the thing is, architecture, all of the disciplines, has it's place, but I was just interested in the bigger ideas part of design, and that seemed to be urban design. So a job came up at Jasmax and I was like, oh cool, I'll give that a shot. And that's where it kind of started from there under Al Ray.

JK: How have you found it as you've continued on that journey? Obviously you had an interest, and you thought urban design might be the way to achieve some of these things, that'll give that a crack. How do you feel now, a few years later?

HH: Big question.

JK: Loaded question.

HH: I think, my first thing I would say, I still feel really good about the decision that I made to take that path for me, because I think it has enabled me to be involved in projects at a broader scale, and across architecture, landscape, planning, economics and those types of things that I'm interested in. I think I probably didn't really understand what urban design was, and what the environment, the development environment is like in Auckland all the time. I think that sometimes has been probably challenging or revealing, like any growth and education is. But I still see it as a very aspirational discipline, and I think the relationship of urban design to architecture is something that is a continuum and I still see those things not as one or the other, even though I've selected to be in -

JK: This part of the continuum, it's not one or the other, it's yeah, like you said a continuum, and you're just kind of sitting here, rather than maybe over here where you would have been before.

HH: Yes, yeah. And I think that shifts too, you know, like you start in architecture, and I've moved into urban design, and who knows where I'll end up.

JK: I asked Haley about the role and relevance of The Treaty of Waitangi within the built environment professions.

HH: So yeah I think there's a really strong place in design now for recognising the tino rangatiratanga of place, or of tangata whenua. And, I think to me it means that the environment is then considered from a holistic point of view, and it's considered as a taonga, and as soon as you make that transition in your thinking of the environment as a taonga you take a duty of care around it that's much different to looking at it as a product or an object for development sole purposes. And that is a fundamental thing that I think the Treaty offers New Zealand and that partnership offers New Zealand going forward. And when you look at resource management, urban design, architecture and development, if we have that kind of embrace from Māori, and Pākehā who come on board with it, it's a really beautiful thing. Because, it means that you take on the idea of being kaitiaki. You take on the idea and the responsibility of being kaitiaki, and you're stopping to take the time to understand the land, and the importance of the land, and everything that that offers, first. Before you start to look at how you may intervene into that space. And that's, like, phenomenally important. The Treaty offers New Zealand or Aotearoa an opportunity to acknowledge and uphold a relationship between two people, but it also has an opportunity for us as designers to really create an incredible country - which we already have - but in an urban way.

JK: I really like that whakaaro, I'm glad you took it there.

HH: Part of the thing that I find really interesting is the conversation or the kōrero around New Zealand being a bicultural place, but co-governance and co-management. And how those types of ideologies are evolving. I know that they're still developing and there's a lot of teething problems in those areas, but I am really inspired by the fact that we are going down that path, that we have started on that path. We started on it a long, long time ago, but that we in this modern contemporary context are discussing things like co-governance and co-management, because we shoul