In Conversation with Carin Wilson

Description

EPISODE SUMMARY: On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism, we speak with Carin Wilson, a Ngāti Awa artist, designer and craftsperson, whose urban and built works include public and private projects with a cultural focus, frequently created in collaboration with architects, designers and other artists.

GUESTS: Carin Wilson

FULL TRANSCRIPT:

Jade Kake: Tēnā koutou katoa

Nau mai haere mai ki te Indigenous Urbanism, Aotearoa Edition, Episode 4.

I’m your host Jade Kake and this is Indigenous Urbanism, stories about the spaces we inhabit, and the community drivers and practitioners who are shaping those environments and decolonising through design.

On this episode of Indigenous Urbanism we speak with Carin Wilson, a Ngāti Awa artist, designer and craftsperson with studios in Te Tai Tokerau and Tāmaki Makaurau. Carin’s urban and built works include the origination and development of public and private projects with a cultural focus, frequently in collaboration with architects, designers and other artists.

Carin is a significant figure in New Zealand art and design, and has had a career in the arts spanning more than four decades.

We sat down with Carin at his home in Mt Albert to discuss his life and his work.

Ko wai koe? Nō hea koe?

Carin Wilson: Ko Pūtauaki te maunga, Ko Mātaatua te waka, Ngāti Awa te iwi, Ko Te Awa o Te Atua te awa, Ko Moutohorā te motu, Ko Te Rangihouhiri te hapū, Ko Tiaki Mahiti Wirihana or Wilson tāku papa, Ko Nina Estarina Bianca di Solma tāku mama, Ko Carin Wilson ahau.

JK: Kia ora. Where to start? You've had such an interesting career spanning 40-something years and you've done all sorts of really amazing things. But what I thought I'd start with is, how did you end up in this area of design, and craftsmanship, and art, and architecture, and all those things meshed together. Yeah, where did it all start?

CW: It started with questions about what's making sense. So my dad had, while he flew fighter aircrafts in the Pacific, he actually studied for a law degree when he got back from the war. And the conversation in my family from as early as I can remember was that I would study law. And I did. I went to Victoria, and Canterbury, and studied law for 3 years, got half a degree. But by the time I'd got that far down the path I just knew that it wasn't going to be a lifetime's commitment for me. I just couldn't. There's not enough creativity or, I couldn't measure the potential for creativity at that stage of my life. I possibly could have taken a different view if I was more mature.

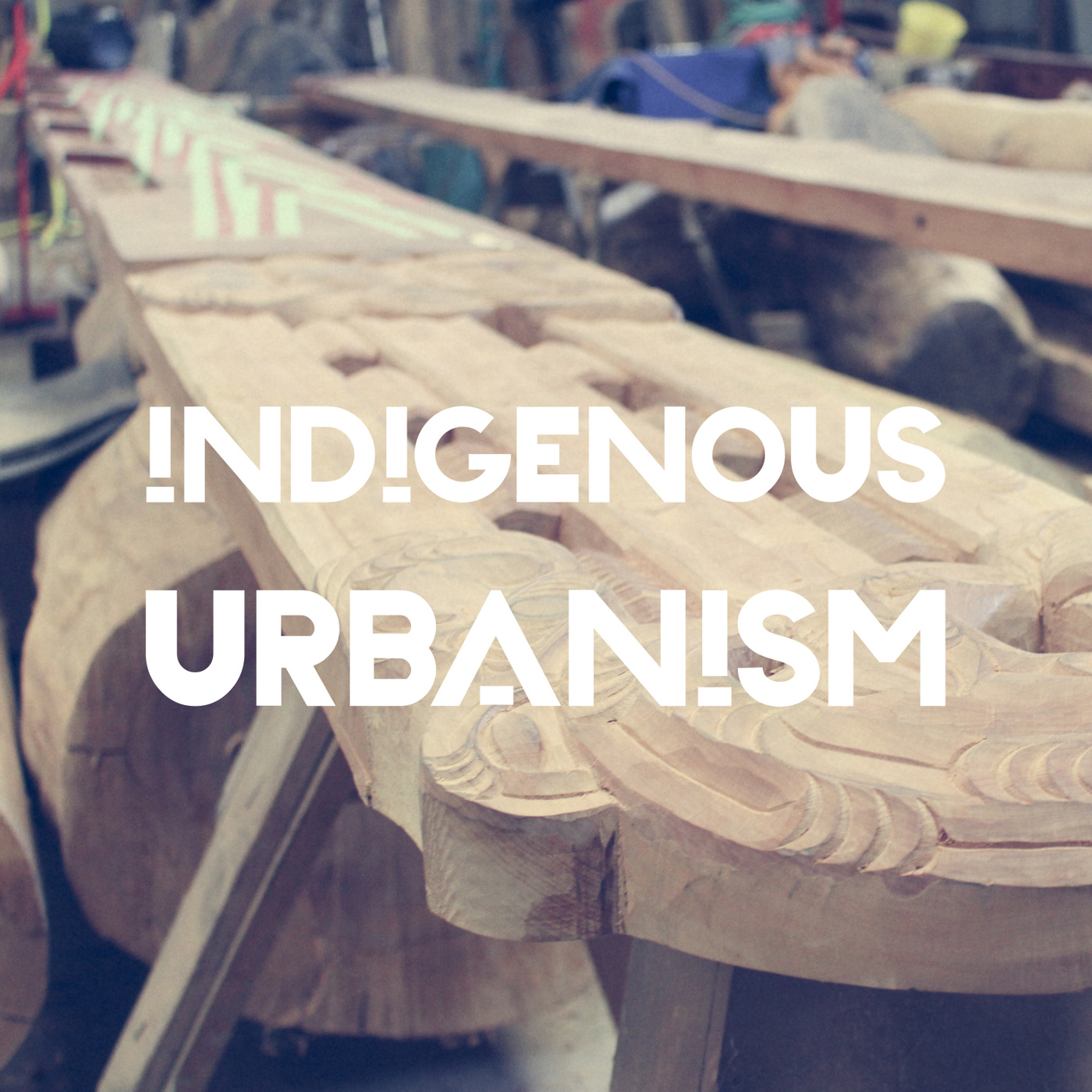

But what I was looking for was a connection, and I can kind of describe that connection now as between the head, the hands and the heart. And I wasn't finding it in what I was discovering the use of law in our society. So, how do I go about this? There's no training, no formal training available. But, I couldn't resist the inquiry about understanding materials, and putting things together, and putting materials together, and it could have been anything at that stage. But I discovered this deep affinity and connection with timber, with the rakau, the wood. And that was the moment that it all changed for me. I discovered a material that I loved, I discovered that what lived in that material was what I would now call the mauri, because I understand what that means. But I certainly didn't at that time. It spoke to me, and it's quite weird but deep spiritual connection and I've always been interested in that dimension of our lives. So to go on exploring that, and see what came out of it, by working with the rakau, with the timber, and fashioning anything with it. Just as a way of engaging deeply with it, was the beginning of that journey.

JK: I think that's really beautiful, because even when we don't necessarily have the vocabulary or the framework to describe things, there are certain things that we understand on an intuitive level. And sometimes when you learn those things, it's kind of just like remembering things you've always known, rather than learning something new.

You were a leading figure in the crafts movement - what were some of the aims of that movement, and some of the achievements?

CW: I didn't even know that I belonged to any kind of movement. I was just doing what I was doing. It was this discovery path and I was completely absorbed in it and trying to be a father, and husband. So, my daughter Tully was 5 months old, I remember this really, really carefully, and I suddenly became aware of the fact, that here was a little life that I was partly responsible for, and, I'd better get my act together smartly, because otherwise I was going to screw up badly. So, I said to Jen look, this is something that I would really like to do. And she came back with three conditions, which was a really interesting response, and kind of set a really clear framework for us to move forward.

So I was able to make that commitment, and part of that commitment was a discovery path. I talked with anybody that I could find about what was going on for me. And one of the people that I met, was a woman named Vivienne Mountford, who was a weaver. And she told me about the way they - weavers - engage with materials. Like, the same thing that was happening for me. Wow. These people do it with wool, and all about that stuff if twisting the yarn, and feeling the tension and the spring in the yarn, and all of that sort of stuff. Wow, there's another bunch of people who are on a similar path, but with a different material. Then, I discovered who were working in clay, ceramics. Hmm, it's going on for them too. So, pretty soon I found that my first affinity was with people who were working in what we could loosely describe as a craft movement in New Zealand at that time. So, that was my whānau, my creative whānau association. I was hungry for understanding, and I was able to look at what they used as their design drivers, that's what I'd call it know. The way they respond to the material, the way the materials limit the level of flexibility or creativity that they can reply to what they want to do, and I started looking at, okay so there are limitations around timber, and I want to explore them as far as I can, to the absolute limit. So I've got to expand that conversation in whatever way I can. So talking with as many people who are working creatively in different fields became a really important part of my whole journey, oddyssey. And that's why I still love collaboration, because collaboration opens up the opportunity for that conversation to begin anew, in every new project. So I'm still doing it, I'm still doing something that I started forty years ago, and I still take delight in the process as much as it was an important part of my learning curve then.

JK: So what happened next, what happened after that?

CW: A big focus on education. Around about three or four years after I became closely involved in the whole question around education in New Zealand, and how well it contributed to the development of people like me. That's a big question. Well, where are the opportunities for learning in this area? I'm teaching myself, I'm talking to others who are helping me in that journey, but there's nothing formal.

By now I was the President of - what we called a President, you know, Chair, whatever - of the Crafts Council. And they heard the conversation about, we're not providing creative education opportunities for people. We're showing them how to do the rudimentary skills, what we would call today the trade skills, but we're not showing them how to be creative in that context. So, Alan Hyatt, who was the Minister for the Arts at the time, was married to an artist. And he just caught that conversation like that. Oh, of course. So, what he and the Arts Council made available to me, was the opportunity to go and look at what other countries were doing in this area. So I went to Sweden, and the United States, and Great Britain, in particular. Both sides of the United States, completely different on the East Coast to the West Coast. To look at the schools that they had working, the people that were leading those programmes, talking with those people, really just taking it to another level. And then coming back to the Minister and giving him a report suggesting how we might go about it here. And there's already like five years of work involved in that process. By the time we got all of the programmes underway in New Zealand through the polytechnic system and so on, we were into the 1990s. So, I'm not saying that I lost my own creative path during that time, but those were two things that were happening in parallel. And suddenly I was involved in a decision process rather than just being engaged in my own aspirations as a maker, there was something kind of structural about what we were doing.

JK: And I think that speaks to the kind of experiences of a lot of Māori designers and architects and creatives, as we might start wanting to create things, but seeing the structural barriers and the changes that are required at more of a systemic level, we necessarily become advocates, and educators, and all of these other things that are not strictly practice. And hopefully that creates the opportunities or the environment for more of that practice work to be able to happen.

CW: I haven't even begun to mention the Māori dimension of that. I can tell you one event which rocked me, and it just forced me to think, oh no, there's one dimension of this that I really haven't engaged with. And that is when the Crafts Council was meeting I asked Cliff Whiting to come to one of our meetings, so that I could have the other members of the Board engage with a Māori dimension. I was trying to bring that to them, but it's like, as the Chairperson it's like forcing the conversation. And, I felt it was importan