Do You Expect Us to Turn Back Now: Alice Paul and the Fight for Woman Suffrage

Description

Women in the United States began fighting for the right to vote in 1848, and by 1910 they had achieved a few hard-won victories. But success nationwide seemed out of reach. Then Alice Paul arrived on the scene with a playbook of radical protest strategies and an indomitable will. She focused in on one target: the president, Woodrow Wilson. How far would Paul and her fellow suffragists have to go to get Wilson's support?

Dora Lewis was the member of prominent Philadelphia family. She was dedicated fighter for the right of women to vote.

In 1919, Lewis participated in the Watchfires protests, in which suffragists burned the speeches of Woodrow Wilson to reject his hypocricy of speaking about democracy and justice without protecting them for women at home.

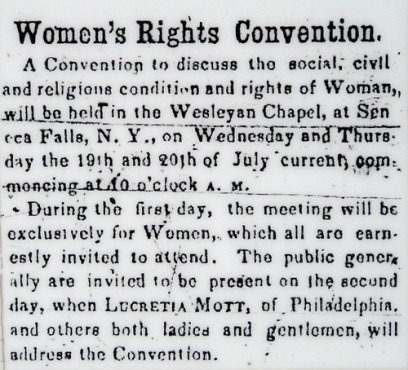

The woman suffrage movement in the United States is usually said to have begun at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. The Convention, organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and several friends and colleagues, produced a Declaration of Sentiments that called for women to "secure for themselves their right to the elective franchise."

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (left) and Susan B. Anthony (right) met in 1851 and become close friends and dedicated fighters for votes for women.

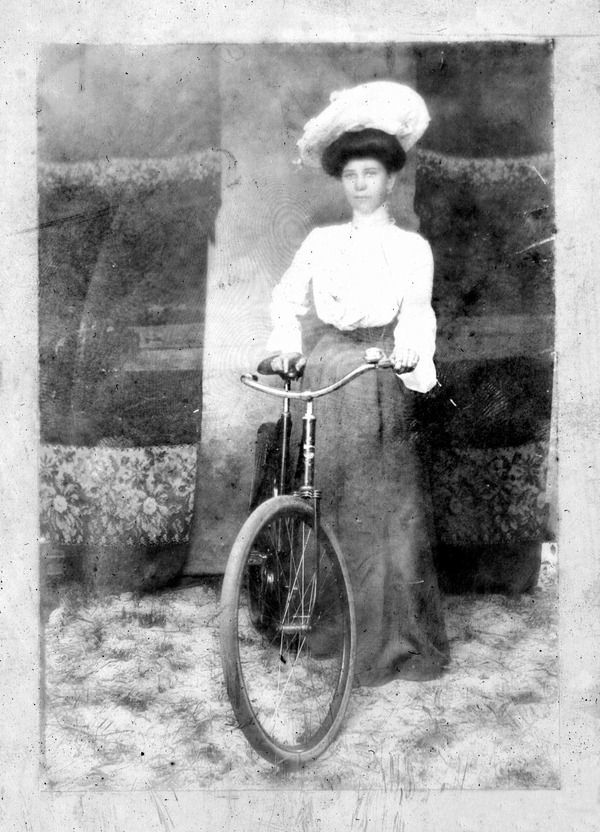

The "New Woman" of the turn of the 19th century was educated, independent, and career-minded. These women were more demanding than previous generations and less concerned about upsetting gender norms.

I joked in this episode about New Women and their bicycles, but this was actually an enormous breakthrough for women. For the first time, women had freedom of movement that opened up a world that been narrowly restricted for previous generations.

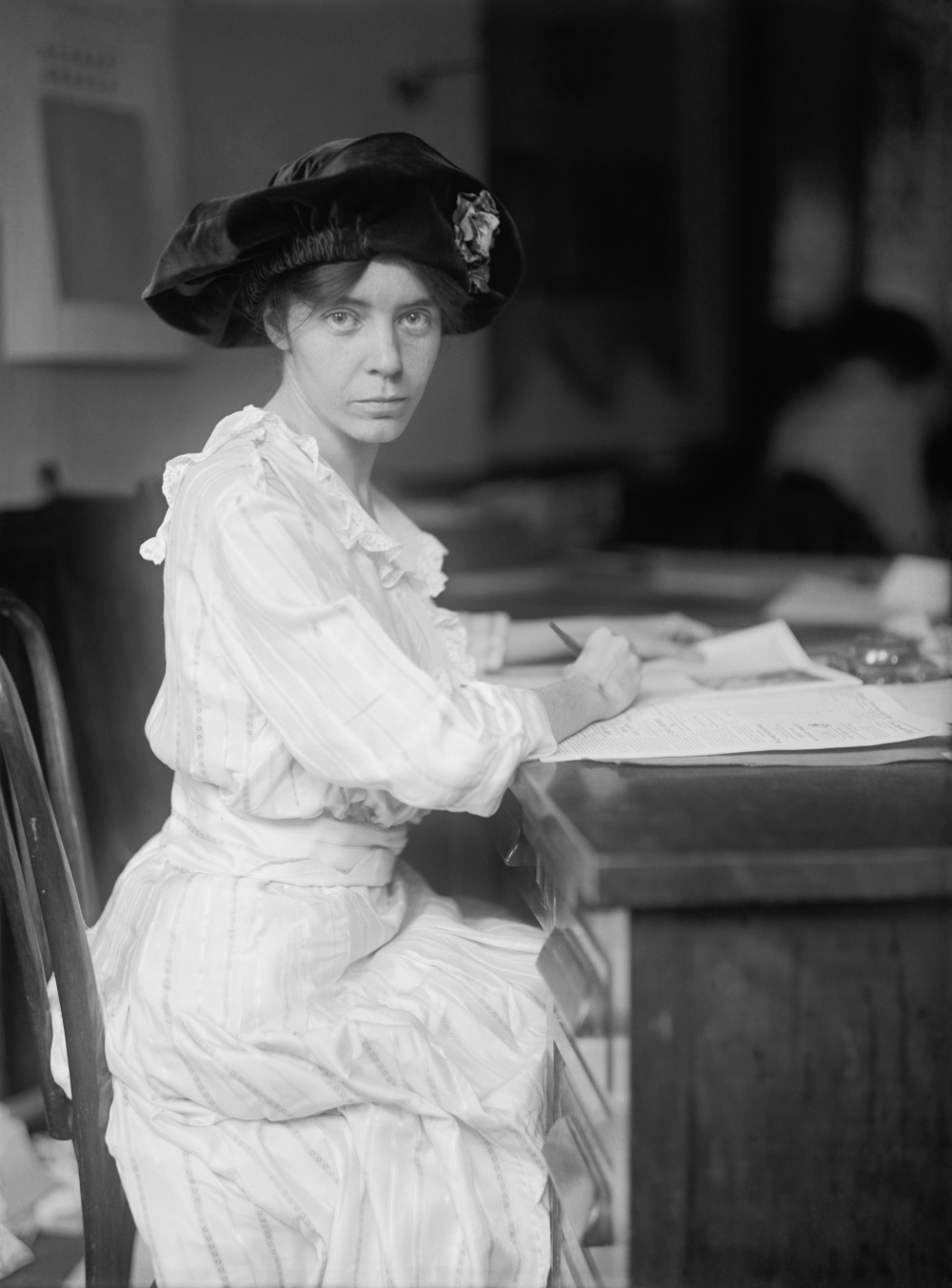

Alice Paul was charismatic, magnetic, and impossible to refuse. She was willing to work herself into the hospital and expected the same level of effort from her friends. (She is also, in this photo, wearing an awesome hat.)

Alice Paul spent the years between 1907 and 1909 in the United Kingdom, where she joined the radical suffragette movement. She learned the power of protest in England, as well as the power of her own will.

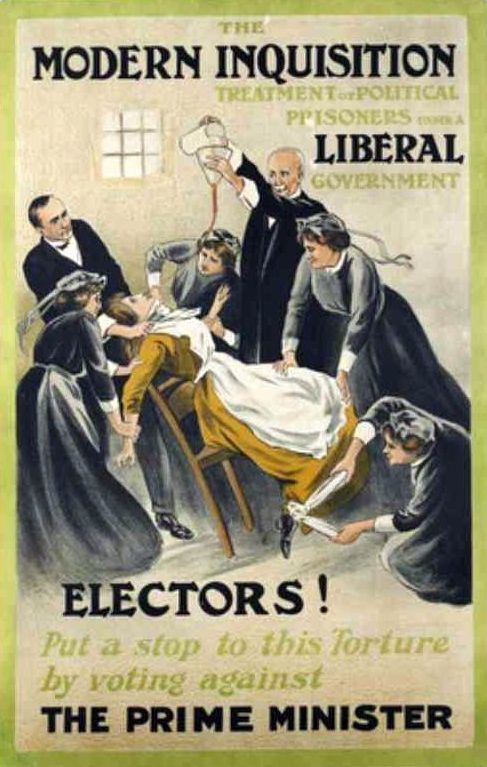

In 1909, Paul went on a hunger strike in prison and was force fed. This was a horrifying, traumatic experience--a fact that the suffragettes didn't hesitate to leverage in their promotional material.

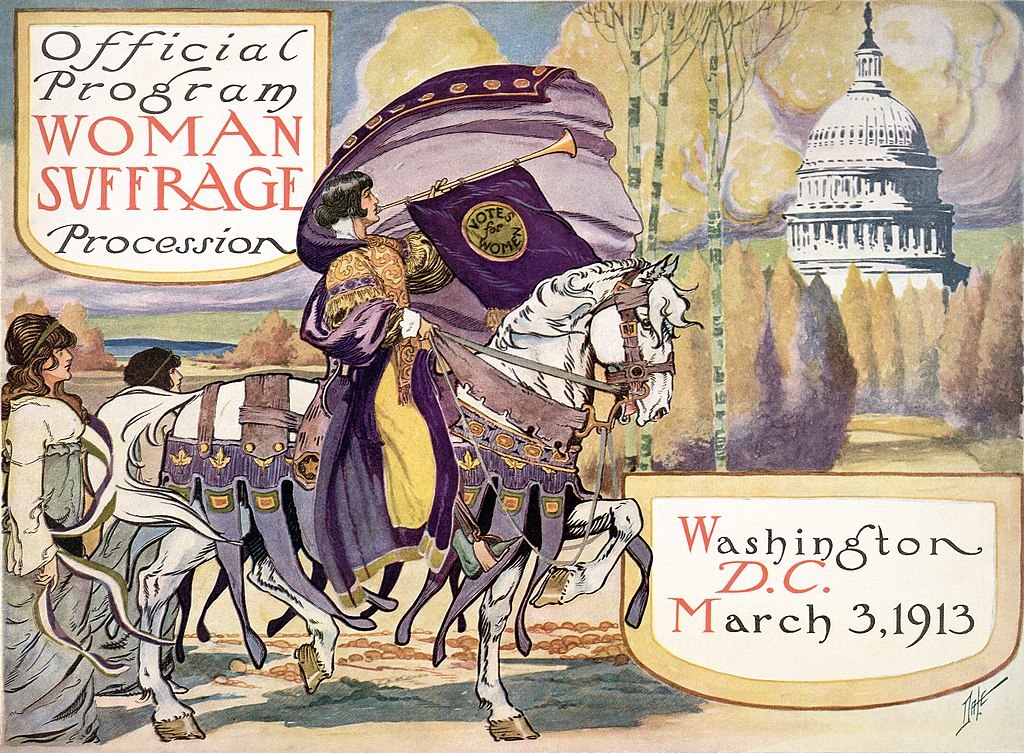

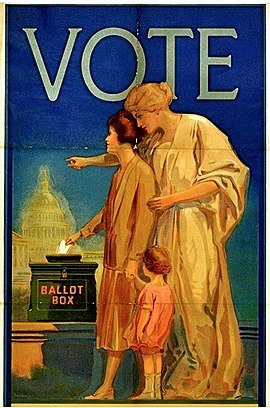

Paul's first major action back in the United States was the Woman Suffrage Procession of 1913. Scheduled the day before Woodrow Wilson's inauguration, it achieved maximum publicity for the cause. This image was used as the cover of the official procession program.

This photo shows the start of the procession, with attorney Inez Mulholland on horseback.

Paul and other organizers intended to segregate African-American marchers to the end of the parade, but Ida B. Wells-Barnett had no intention of being segregated. She joined the Illinois delegation halfway along the route.

Massive crowds viewed the parade. Without adequate police monitoring, the crowd got out of control, spilled into the street, and began harassing the marchers.

In 1917, the Silent Sentinels began protesting daily at the White House. They carried banners demanding the president take action on women's right to vote.

For several months, the protests were peaceful. But Paul began cranking up the tension in the summer, and D.C. police began arresting and detaining the protesters.

Eventually, suffragists were sentenced to time at Occoquan Workhouse a grim, remote facility. Here several suffragists, including Dora Lewis, pose in their prison uniforms.

Suffragist prisoners began protests in prison, refusing to wear uniforms or do assigned work. Some, including Alice Paul, went on hunger strikes. Prison guards reacted with increasing violence. Here one of the suffragists has to be helped to a car after a harrowing stay at Occoquan.

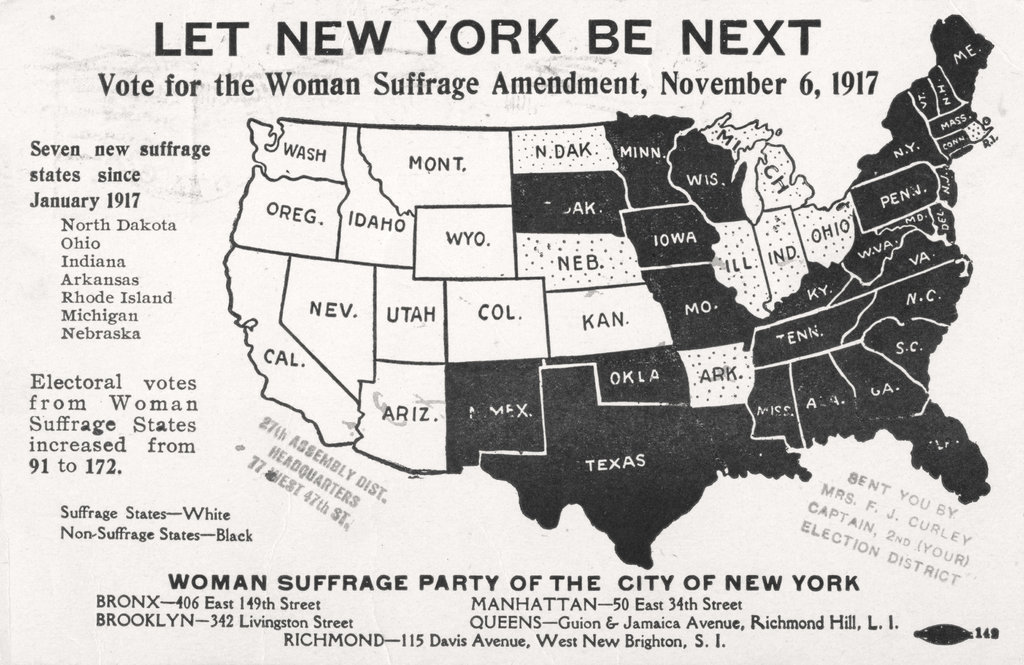

At the same time the members of the NWP were protesting daily at the White House, members of the rival organization NAWSA were conducting a massive campaign for suffrage in New York. They won the vote for 2 million women and reinforced the nationwide conviction that the time had come for a federal amendment.

The New York campaign was one of the most inclusive in suffrage history. NAWSA partnered with both the Wage Earner's Suffrage League and the New York City Colored Woman Suffrage Club. African-American suffrage clubs were popular in northern states; this image is of such a group. (I was unable to figure out exactly where these women were from.)

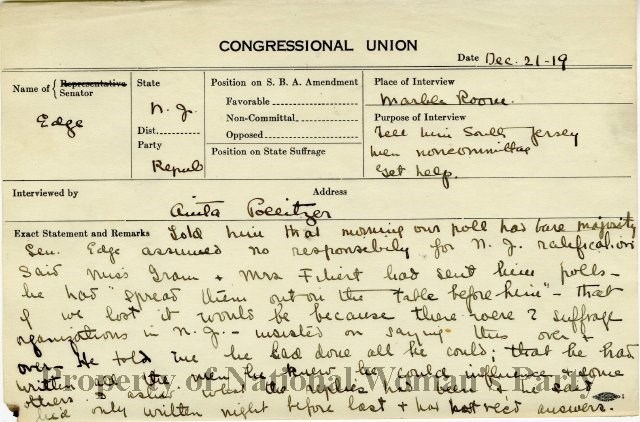

After the House of Representatives passed the federal woman suffrage amendment in 1918, the NWP and NAWSA set aside their differences and worked together to lobby Senators for votes for women. They developed an early form of a database in an index card system that tracked each Senator's friends, memberships, and donors. They also logged notes of each meeting with a Senator, as you can see in this card.

When the amendment failed to pass the Senate in 1918, the NWP began its Watchfires protests burning the president's speeches and even an effigy of the man himself. Crowds inevitably gathered, as seen in this photos, and often the women were arrested.

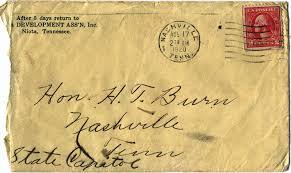

In the summer of 1919, Wilson finally took decisive action, and the House and Senate passed the woman suffrage amendment. The fight moved to the states for ratification. Eventually it all came down to Tennessee the vote of one man, Harry Burn. This is a photo of the letter from Burn's mother that was delivered to him the morning of the vote that made him decide to vote "aye" for suffrage, knowing his constituency would not approve.

Women across the country celebrated the passage of the 19th Amendment.

NAWSA ev