Flu Fences and Chin Sails: Answering New Questions about the Spanish Flu

Description

Living through the COVID-19 pandemic raises all sorts of new questions about the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919. This episode seeks to answer those questions. We look at the multiple waves of the flu, popular home remedies, who went to the hospital and who stayed home, how the federal government responded to the outbreak, the effect on the economy, resistance to face masks, and how the flu shaped the Roaring Twenties.

Correction: In this episode I state that Arthur Conan Doyle stopped writing mysteries after the flu pandemic. This is simply not true. Doyle published numerous mysteries, including several Sherlock Holmes stories, between 1919 and his death in 1930. My apologies for the error, and thanks to the listener who caught it.

Heroic efforts went into creating a vaccine for Pfieffer's Bacillus, which was believed by many doctors to cause the Spanish Flu. These efforts were all in vain, since Pfeiffer's Bacillus is a fairly common bacteria and not the cause of the flu. The actual cause would not be understood until the existence of viruses was proven in the late 1930s.

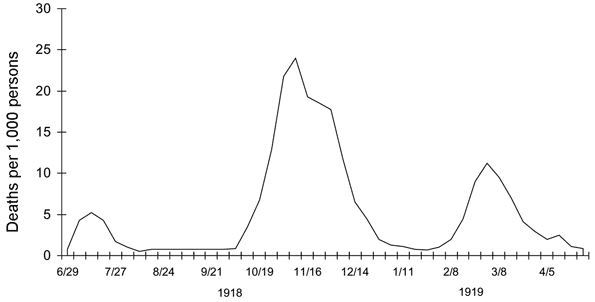

The Spanish Flu hit in three waves, in the the spring of 1918, the fall of 1918, and the spring of 1919. There is no evidence that the relaxing of social distancing and/or quarantines triggered the second wave. It is more likely that the virus mutated into a more easily transmitted and more deadly form over the summer. However, the third wave can be linked to relaxed social distancing.

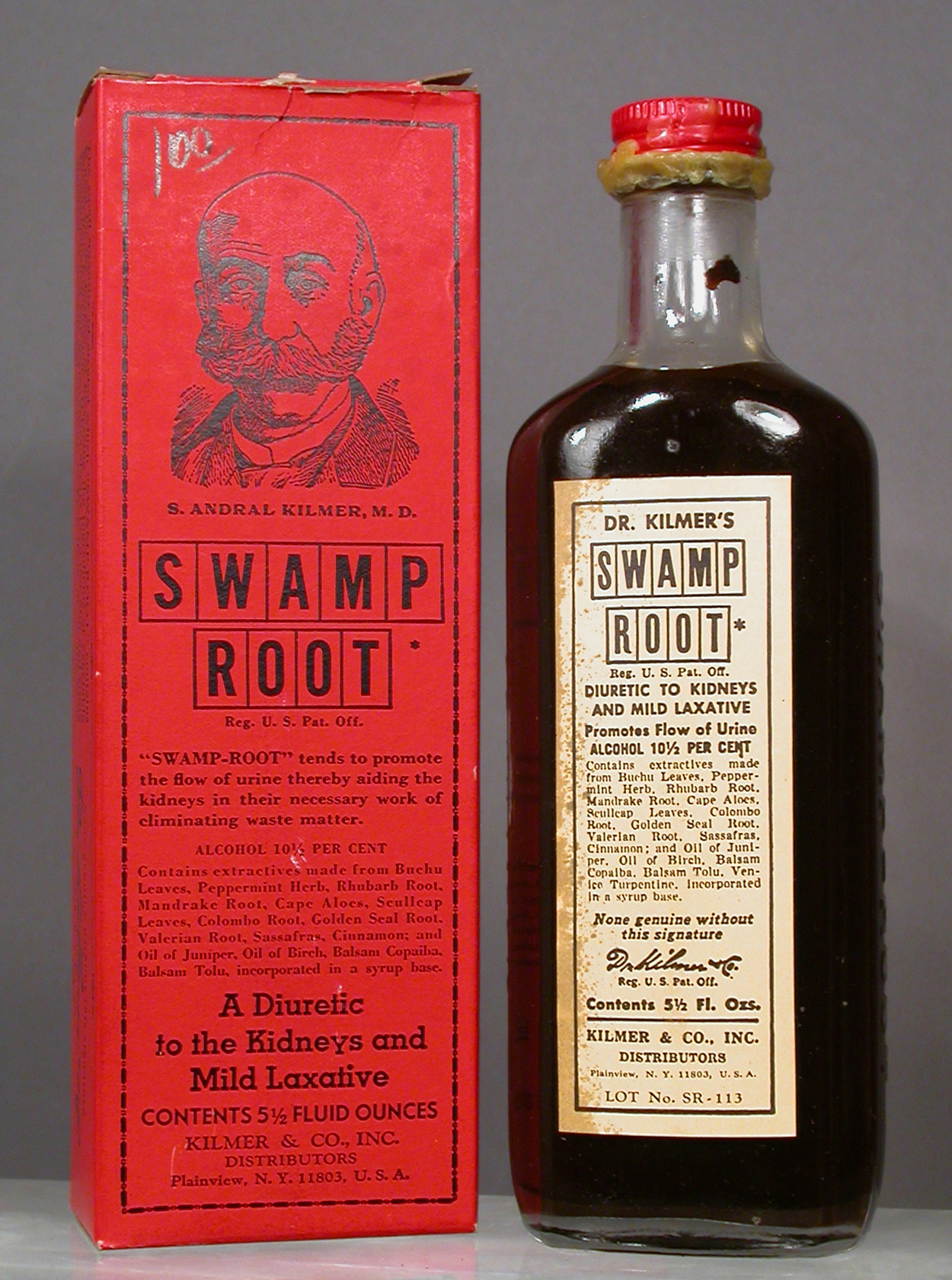

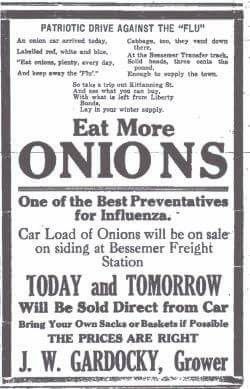

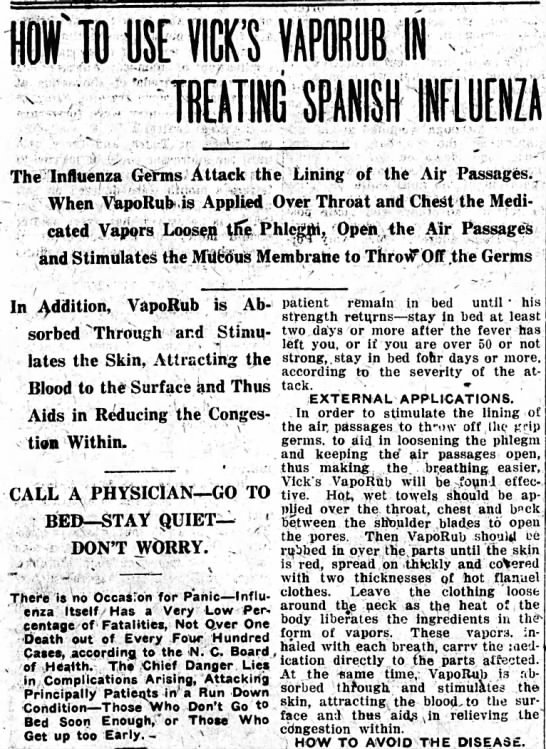

Dr. Kilmer's Swamp Root was a popular patent medicine used to treat the flu. So were onions and Vick's Vapo-Rub.

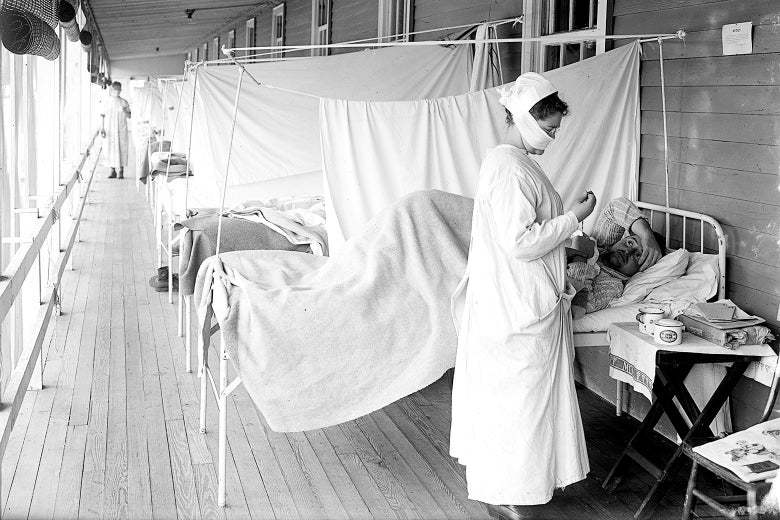

Nurses played an enormous role during the Spanish Flu, perhaps a greater role than doctors, since recovery was largely the matter of careful nursing. A severe shortage of nurses put a huge burden on those trying to treat patients.

The American health system was strictly segregated in 1918-1919, and nurses of color struggled to treat the patients that overwhelmed the small and underfunded African-American hospitals.

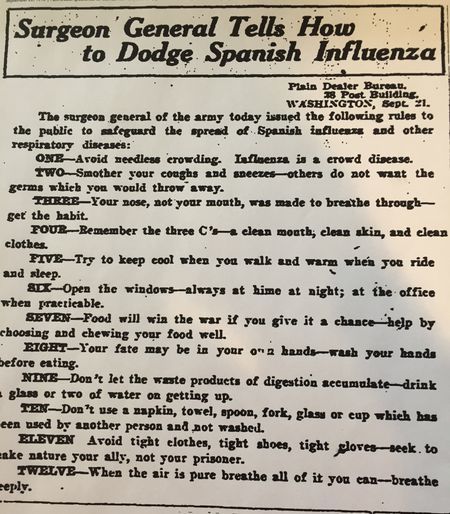

There was no precedent in 1918 for the federal government to play anything other than a coordinating and research role during the Spanish Flu. But the situation was so dire that states and cities begged for help. Surgeon General Rupert Blue seemed unable to rise to the challenge.

The Surgeon's General's advice on how to avoid the flu was distributed widely but offered little in real help and failed to acknowledge the severity of the situation.

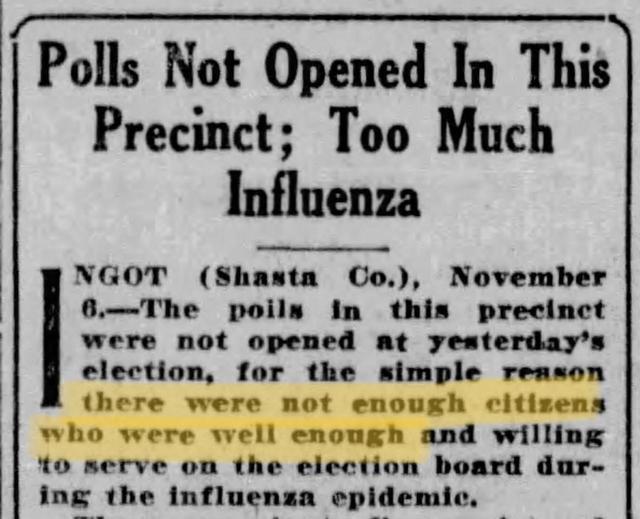

The 1918 mid-term election went ahead as planned, but in parts of the west, polling places were unable to open because too many workers were sick with the flu.

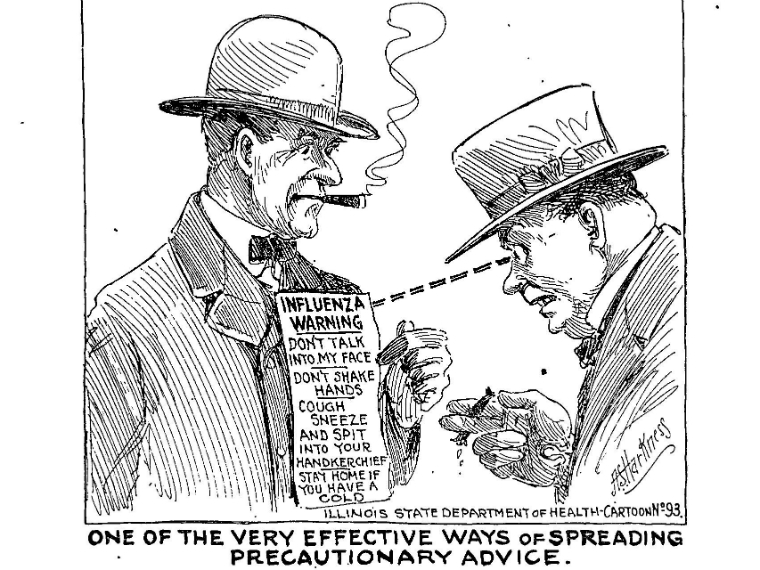

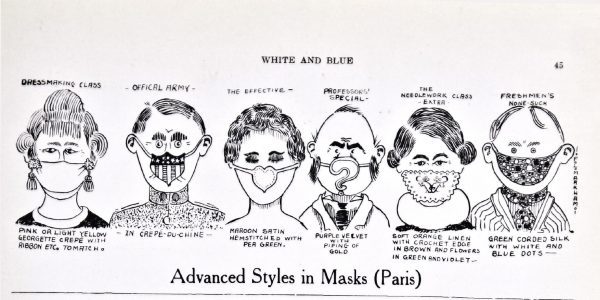

Public campaigns urged individuals to cover their faces when coughing or sneezing and to avoid shaking hands. If this cartoon is any indication, some people thought the efforts were extreme.

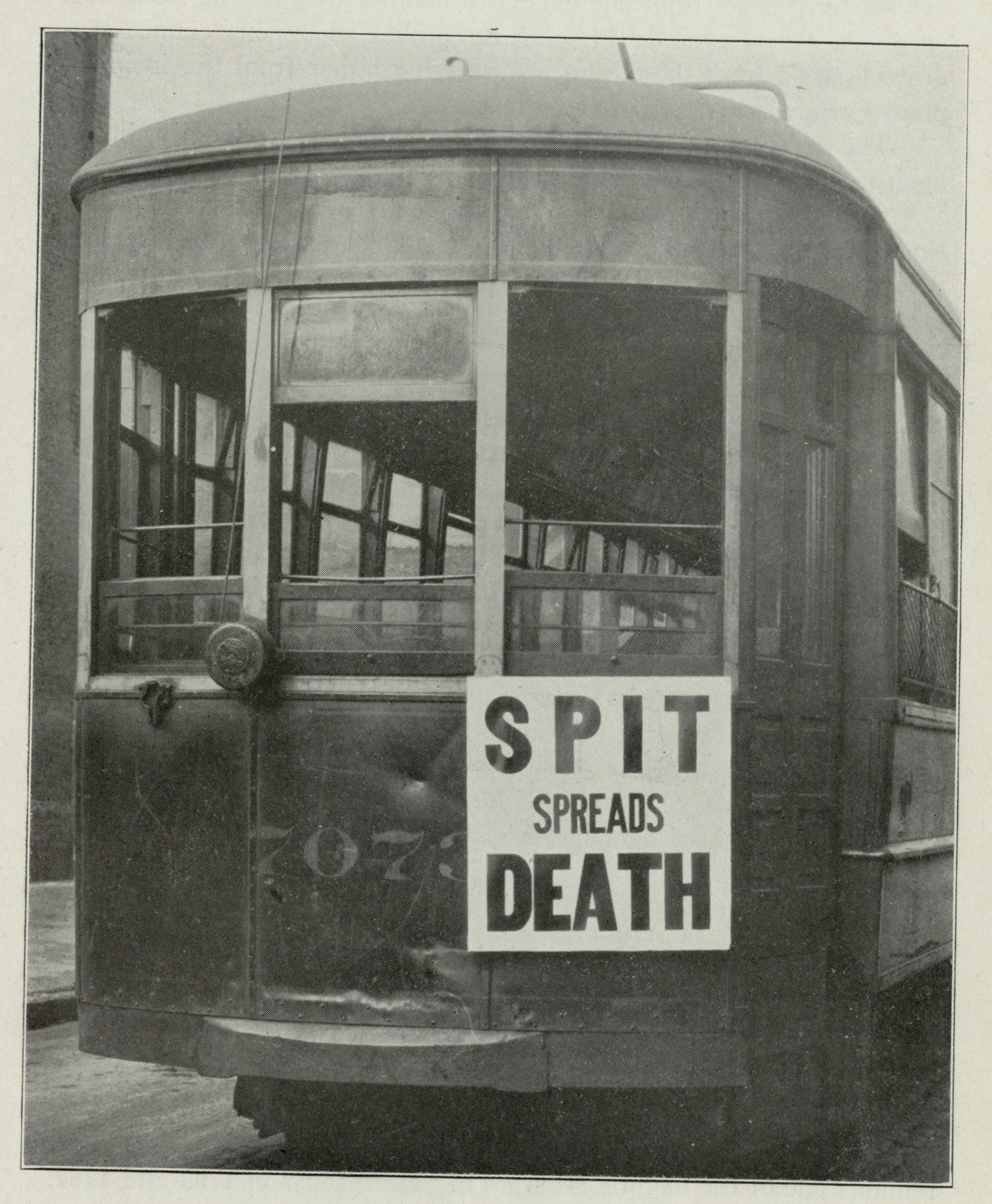

Cities railed at residents to stop spitting on the street. This was an enormous problem, although this warning seems particularly stark.

Masks were adopted across the country, and some cities mandated their use. The masks became a symbol of the disease. This cartoonist pokes fun at their ubiquity by proposing new styles soon to come out of the Paris fashion houses.

San Francisco required residents and visitors to wear face masks, and initially compliance was high. Red Cross workers sold masks at ferry terminals and on the street.

But people soon tired of wearing masks, or wore them slung around their necks. Soon police and public health officers were busy fining and arresting scofflaws.

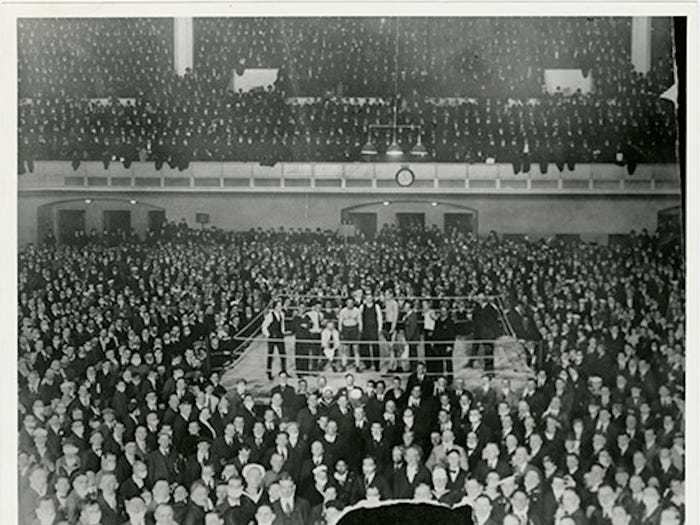

Crowds packed the Civic Auditorium for a boxing match in November 1918, and a photographer snapped this image of hundreds of San Franciscans without a mask in sight. Dozens of city leaders were fined for violated the mask ordinance. The ordinance was lifted a few days later.

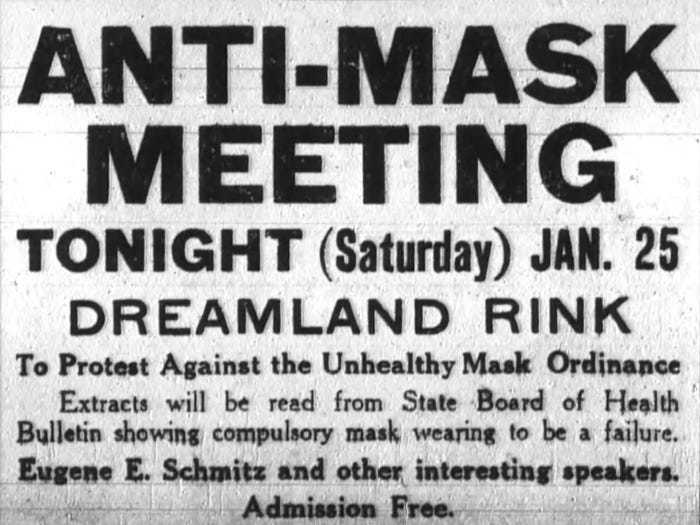

However, the ordinance was re-imposed in January when the flu returned to San Francisco. This time, opposition to masks was not just heated but organized. An anti-mask league held a meeting to which up to 5000 people attended.

Violet Harris was 15 years old and living in Seattle when the flu closed schools. She kept a diary that gives a sense of life during the shut down.

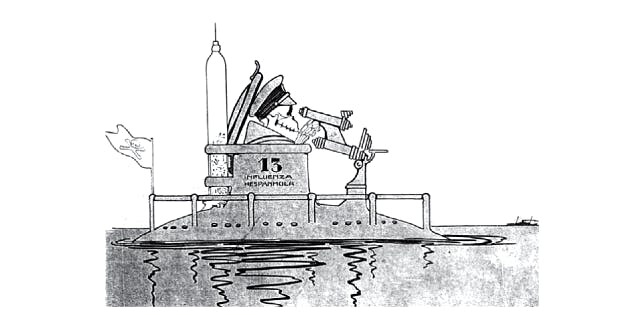

Some rumors traced the flu pandemic to German scientists and claimed the disease was spread by German submarines. This Brazilian cartoon conveys in this a rather grim way.

Hundreds of thousands of children were left orphaned by the Spanish Flu. This photo shows a group of children who lost their families when the flu raged through the Bristol Bay region of Alaska.

Links:

- Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World, by Laura Spinney, Amazon

- The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History, by John M. Barry, Amazon

- Influenza 1918 | American Experience | Official Site | PBS

- "Influenza 1918: Searching for Cures," American Experience, PBS

- "Did Lack of Social Distancing in 1918 Pandemic Cause More Deaths Than WWI?", by Dan Evon, Snopes.com

- "Why the Second Wave of the 1918 Spanish Flu Was So Deadly," by Dave Roos, HISTORY.com

- <a title=""Aspirin Misuse May Have Made 1918 Flu Pandemic Worse," ScienceDaily" rel="nofollow" href="https://www.scie