Giving the Natives a Free Hand: The Irish Fight for Independence

Description

The Irish had tried to free themselves from British control for centuries, always to fail. But in 1922, the Irish Free State took its place among the world's independent nations. Learn how an election, a shadow government, and a key literally baked into a cake brought independence to Ireland--along with a bloody civil war.

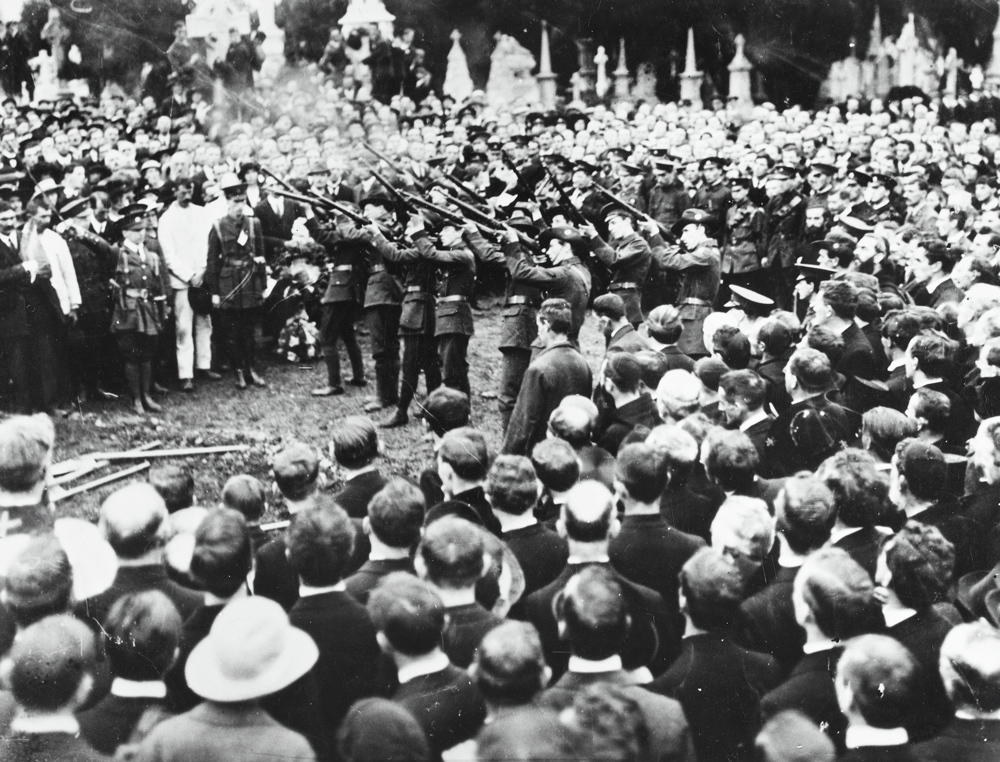

Thomas Ash died in a British prison in 1917 after a botched forced feeding when he refused to lift his hunger strike.

His funeral had every appearance of a state funeral, even though when Ash died he was considered a traitor by the British. Here a squad from the Irish Volunteer Army fire a volley at his graveside.

The day after Easter 1916, Irish nationalist rebels seized key locations in Dublin in an attempt to spark a national uprising. Few photos were taken by the rebels. This rather poor quality image is one of the only in existence; it was taken from within the General Post Office and shows several soldiers. Notice how young many of them are.

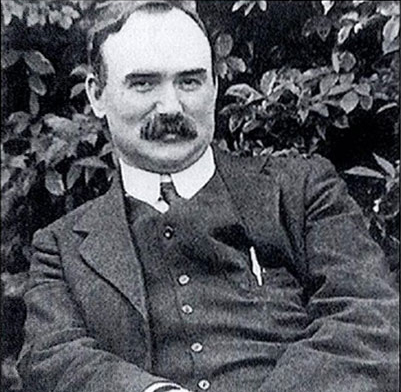

James Connally led forces in the General Post Office. He was praised for his courage and determination; Michael Collins later said he would have followed him through hell.

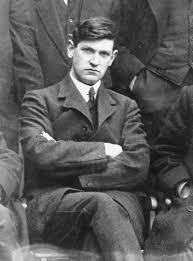

Michael Collins was young, dashing, and handsome--and relatively unknown before the Rising.

The American-born Eamon de Valera led troops in the southeastern part of Dublin.

Within a day of the rising, British troops began pouring into the city and quickly overwhelmed the rebels.

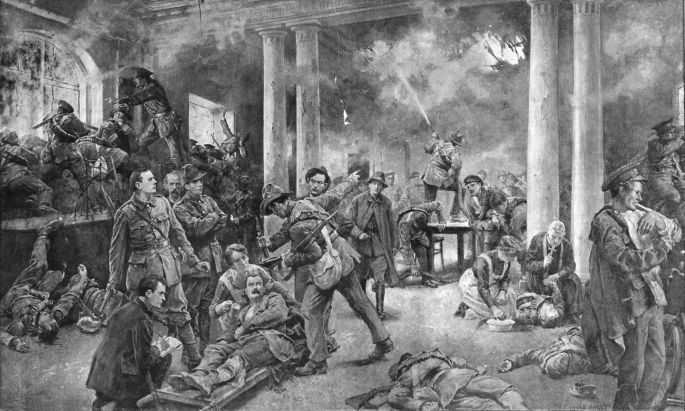

The situation rapidly deteriorated for the rebels. This drawing is an artist's depiction of the last day with the General Post Office. Notice the smoke from fires and the wounded Thomas Connally lying on a stretcher. On Saturday, they had no choice but to surrender.

Dublin was left in ruins and 260 civilians were left dead.

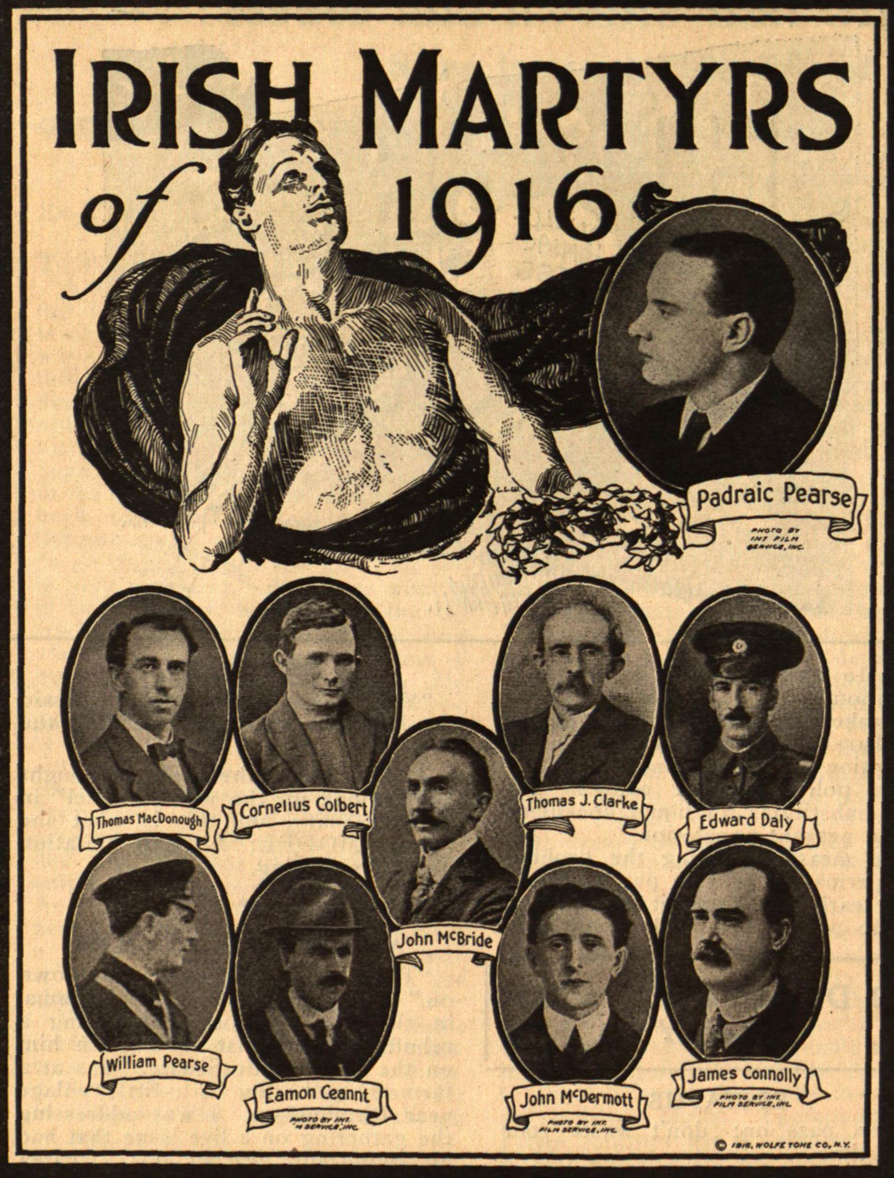

The British rapidly executed 16 men, inadvertently turning public opinion against them and creating a whole host of martyrs to the Irish cause. Commemorative posters like this were popular across Ireland.

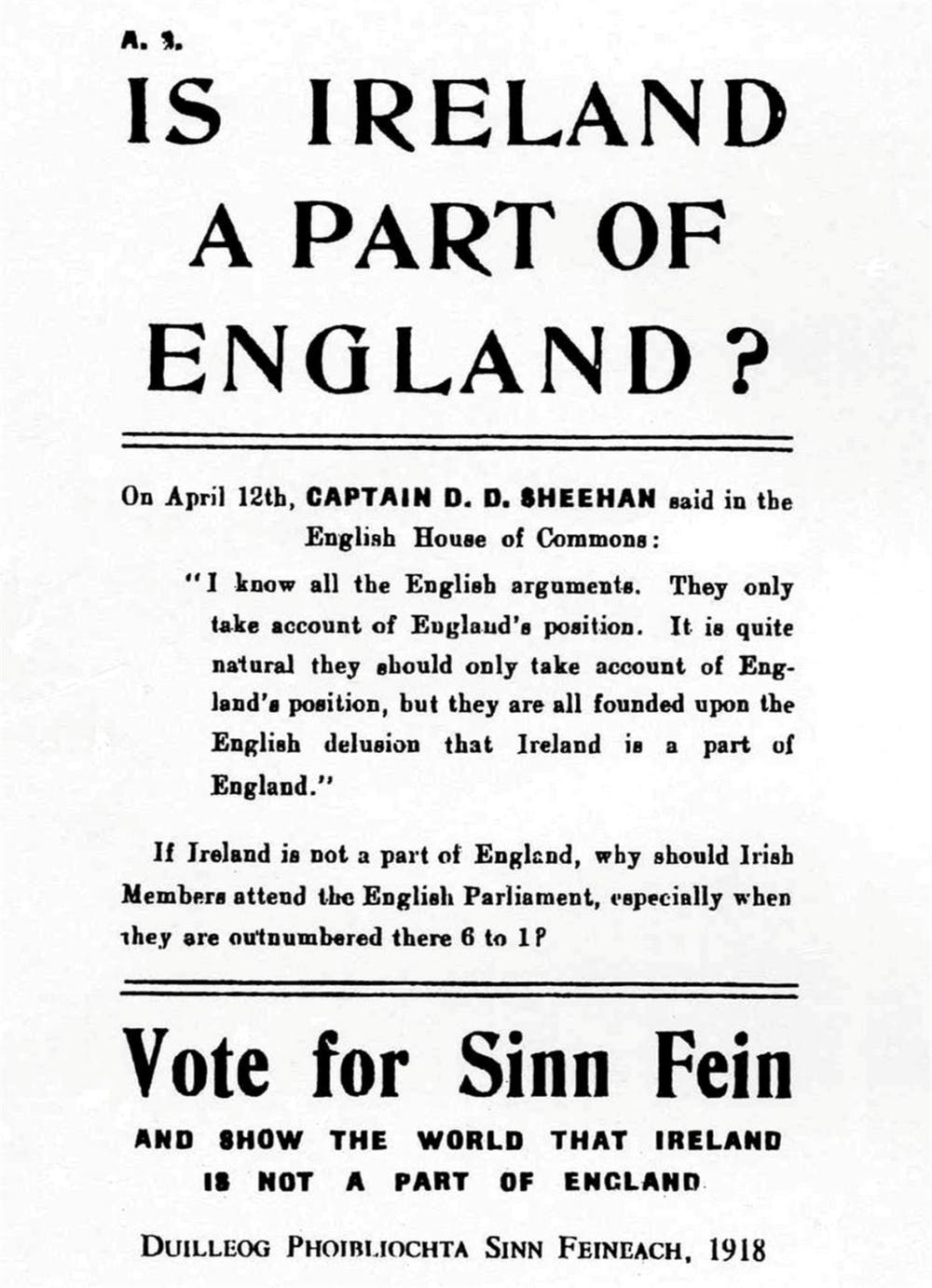

Irish republican leaders poured their efforts into winning the vote in the 1918 general election. They framed the election as a mandate on Ireland's future--and won.

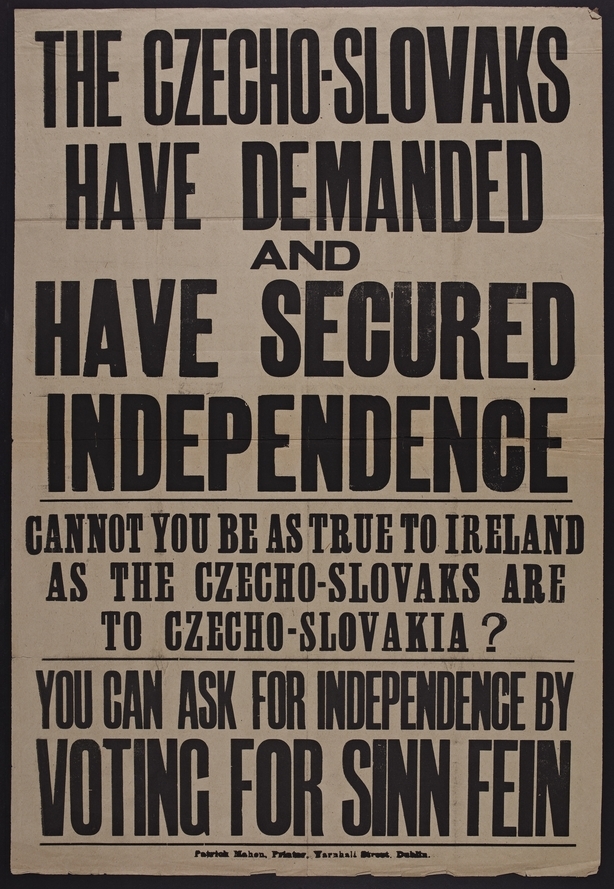

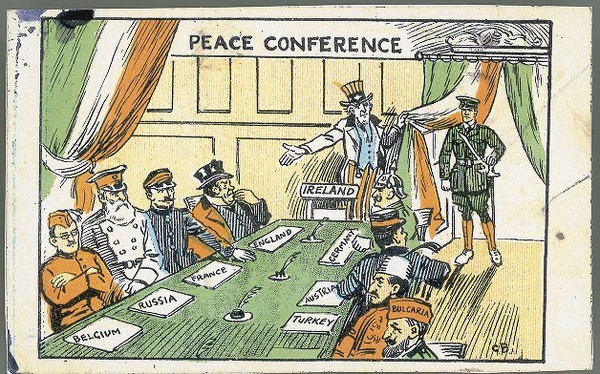

The Irish were well aware of the fight for self-determination among other European nations such as Czechoslovakia. When the Peace Conference opened in 1919, the Irish argued they deserved independence as much as the Czech or the Poles, sometimes using blatantly racist arguments.

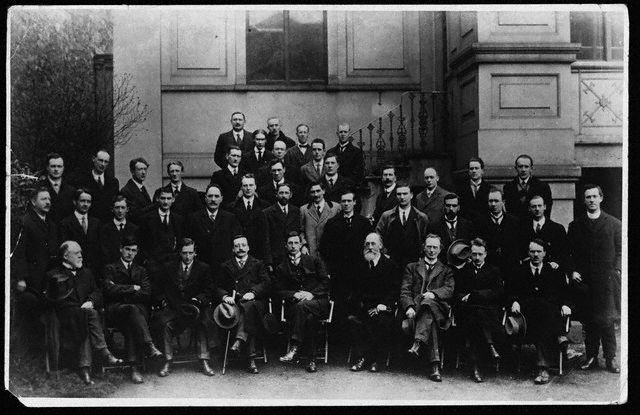

The first Dail Eireann, or Irish national assembly, moved rapidly to create a shadow government in early 1919. Michael Collins, the minister of finance, is second from the left; Eamon de Valera, president, is fifth from the left.

Irish-American activists urged Woodrow Wilson to take up the cause of Ireland at the Paris Peace Conference. This postcard is a political cartoon that shows Uncle Sam escorting Ireland into the conference. Wilson refused to address the issue of Ireland, following the insistence of British Prime Minister David Lloyd-George that Ireland was not the business of the conference.

Wilson would pay for this decision when Irish-Americans organized against the League of Nations and helped ensure its defeat in the the U.S. Senate.

Eamon de Valera spent most of his first two years in office touring the United States to raise money and support for Ireland. He toured the entire country and made a remarkable visit to the Chippewa reservation in Wisconsin. He greeted the Chippewa as a representative from one oppressed nation to another. The Chippewa adoped de Valera as a member of their tribe and gave him this magnificent headdress.

Meanwhile, back in Ireland, IRA units systematically targeted members of the Royal Irish Constabulary, killing and wounding hundreds. The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Sir John French, denounced Sinn Fein as a "club for killing policemen."

The British responded to the RIC attacks by sending in veterans of the Great War, nicknamed the Black and Tans for the dark coats they wore over khaki uniforms. The Black and Tans had little training and policemen and imposed a harsh regime of searches (as pictured here), checkpoints, reprisals, and extra-judicial killings (which is a nice way to say they murdered people outright.)

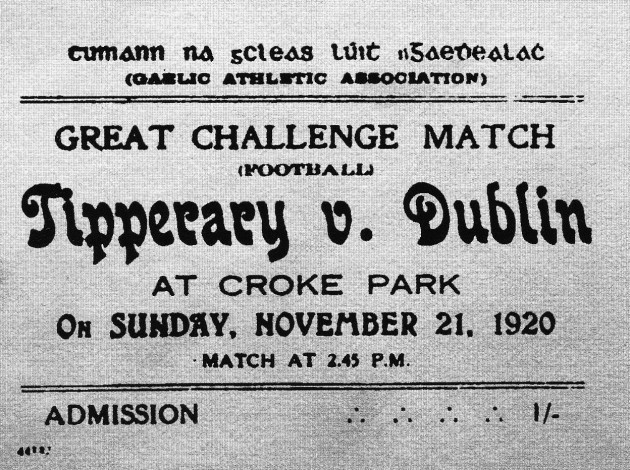

In reaction, the IRA's special assassination unit "The Squad" targeted British spies, killing 11 on Sunday, November 21, 1920. The furious British surrounded a football match between Dublin and Tipperary and fired into the crowd.

Shortly before Bloody Sunday, Terence MacSwiney died after a 74-day hunger strike. His slow martyrdom was followed by the entire world, and other countries started asking the British pointed questions about their policy toward Ireland.

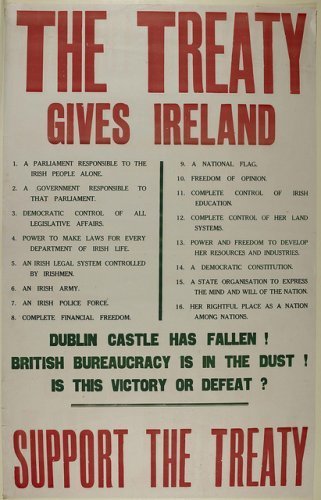

Finally, the Irish and British began negotiating a peace that would remove the British from Ireland--but keep the country tied to Great Britain and divided along religious lines.

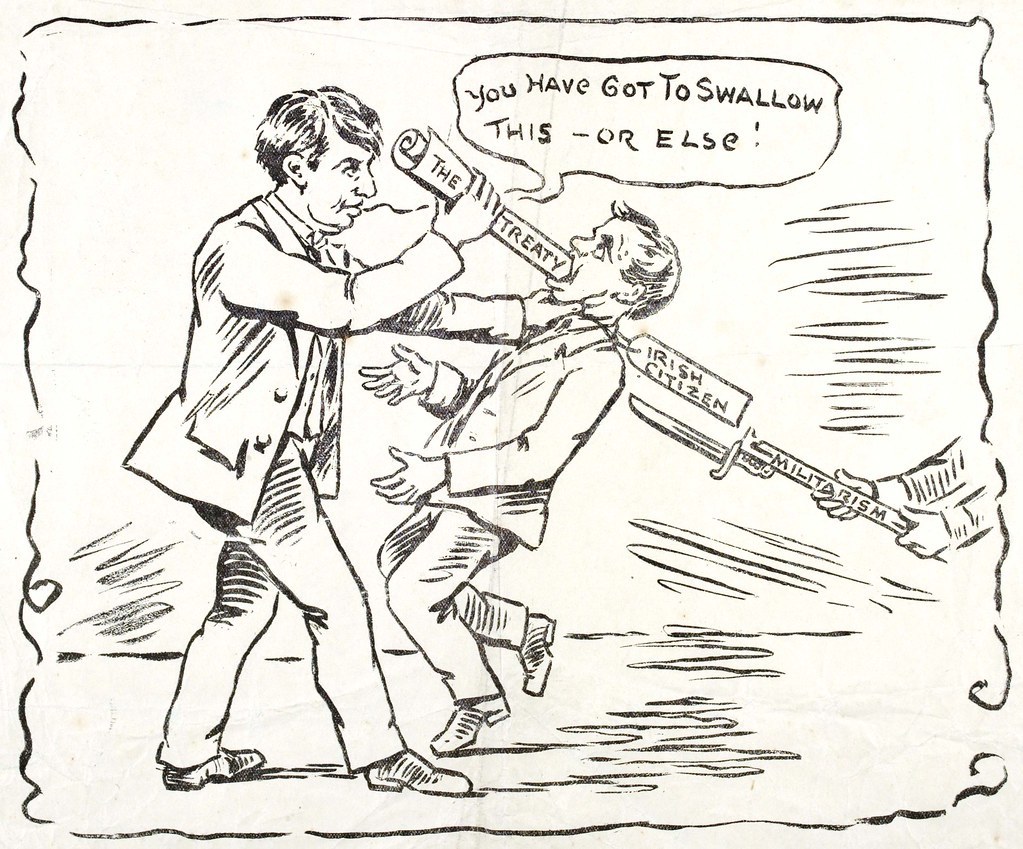

The Irish, led by Michael Collins, signed the treaty, kicking off a bloody civil war. Pro-Treaty forces, led by Collins, argued that the treaty was the right solution for Ireland that guaranteed peace.

Anti-Treaty forces, led by de Valera, argued that the treaty was being forced on Ireland and was a betrayal of all they had fought for.

Collins was winning the fight when he was shot by an Anti-Treaty ambush on August 22, 1922. Collins became the ultimate Irish martyr, always young, always dashing, always a hero.

Within nine months of Collins' death, the Anti-Treaty troops agreed to a ceasefire and peace came to Ireland.

Or, at least, until the Troubles began in the north--but that's another podcast.

- Please note that the links below to Amazon are affiliate links. That means that, at no extra cost to you, I can earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. (Here's what, legally, I'm supposed to tell you: I am a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for me to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.) However, I only recommend book