Radical and Agitator: William Monroe Trotter and the Fight for Justice

Description

William Monroe Trotter was among the richest, best-educated, and most-well-connected African-American men in the United States--and he dedicated every ounce of his privilege into helping his fellow black Americans. By 1919, he had fought with the elder statesmen of his community, been arrested in protests over "Birth of a Nation," and denounced Woodrow Wilson's racial policies to president's face. But 1919 would bring one of Trotter's greatest challenges: he would need to learn how to peel potatoes.

William Monroe Trotter was one of the most significant civil rights leaders in Amerian history, yet he is little remembered today.

Trotter crossed the Atlantic on the SS Yarmouth as assistant cook--a strange position for a Harvard graduate with two degrees and a Phi Beta Kappa key.

Trotter's father James Monroe Trotter fought in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. Afterward, he served as the first Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, a lucrative position where he earned a small fortune. James' only son William would inherit both wealth and influence, but James insisted that this privilege should be employed to fight for African-American rights.

In 1899, William Monroe Trotter married Geraldine Pindell, known by friends and family as Deenie. She was passionate about civil rights as her husband.

A year after his marriage, Trotter decided to fulfill the mission laid upon him by his father by publishing a newspaper, The Guardian. The weekly was dedicated to exposing racial issues across the United States.

In 1905, Trotter, along with W.E.B. DuBois and several other black leaders, founded The Niagara Movement to advocate for civil rights and counter the message of the Tuskegee Machine. The organization collapsed within two years, largely because Trotter was so difficult to work with.

In 1909, DuBois joined other activists to establish the NAACP with much the same aims. Trotter rejected the group, which he saw as dominated by white donors and leaders and too timid to tackle real issues. In response, he founded his own organization, which in time would take the name the National Equal Rights League, or NERL.

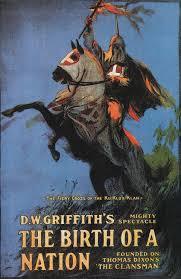

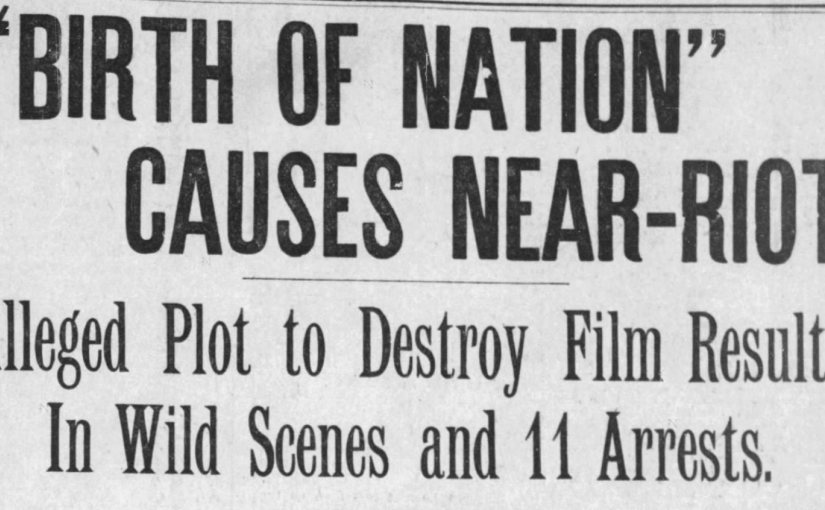

The 1915 film The Birth of a Nation prompted immediate reaction from both the NAACP and Trotter's NERL. But those reactions took different forms. The NAACP focused on legal challenges and attempts to disprove the historical accuracy of the movie. The NERL organized public protests intended to demonstrate the depth of African-American opposition to whites.

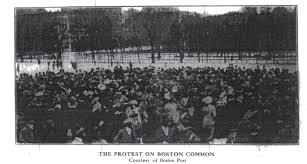

Among the protests Trotter organized was this one in Boston Common. The photo is extremely poor quality, but you can get a sense of the size of the crowd.

At another Trotter-organized event, 11 protestors were arrested for disturbing the peace. Trotter was among them.

At the end of the Great War, a dozen or so other delegates were elected to present an appeal for equal rights and justice to the Peace Conference. Among them were Trotter and Madam C J Walker. Walker has an incredible story--she built her business selling cosmetics and hair care products to African-American women into one of wealthiest and most successful in the country.

At the same time Trotter was trying to get to Paris to present his appeal, W.E.B. Du Bois was organization the Pan-African Congress, which included representatives from African nations and the African diaspora.

When Trotter returned home from Paris, Red Summer had begun. Trotter focused on creating a new organization that would help African-Americans defend themselves, using force against force.

The ABB ceased to be a secret in 1921 when the armed response of African-Americans during the Tulsa Race Massacre horrified white Americans. The ABB was accused of conspiracy with all of the usual suspects of the era, including the Reds and the Wobblies. In this case, the Reds, were, in fact, a factor. Within a few years, the ABB had been absorbed by the American Communist Party.

As these images show, whole blocks of Tulsa were burned to the ground, including the entire Greenwood Neighborhood, known as the "Negro Wall Street." It's unknown how many people died in Tulsa

Links:

- Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter by Kerri K. Greenidge — Greenidge's book was my essential guide during this episode. I highly recommend the book. Trotter fought far more battles than I had time to describe, and Greenidge does a fantastic job of placing his life in the context of the time and place.

- "The Legacy of a Radical Black Newspaperman" by Casey Cep, The New Yorker

- Booker T. Washington (1856-1915)

- "Woodrow Wilson was extremely racist — even by the standards of his time" by Dylan Matthews, Vox

- "The Crisis," NAACP, January 1915 — This issue of "The Crisis" contains Trotter's description of his 1915 encounter with Woodrow Wilson, as well as several responses. The article begins on pages 119. It's also worth look at the other articles for insight into the time.

- "The Birth of a Nation: How the fight to censor D.W. Griffith’s film shaped American history." by Dorian Lynskey, Slate

- <a title=""The Black Activist Who Fought Against D. W. Griffith’s 'The Birth of a Nation'" by Richard Brody, The New Yor